Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5760

Research ArticleOpen Access

Contrast between Adult and Adolescent Suicidal Behavior: Probe in Psychiatric Inpatients Volume 1 - Issue 3

Saeed Shoja Shafti*

- University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (USWR), Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Iran

Received: January 24, 2020 Published: February 05, 2020

Corresponding author: Saeed Shoja Shafti, Professor of Psychiatry, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (USWR), Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Tehran, Iran

Abstract

Introduction: While some of scholars believe that combining adult and adolescent suicidal behavior findings can result in misleading conclusions, some of researchers have stated that suicidal behavior may be a different phenomenon in adolescents than in adults. Hence, in the present study, the clinical profile of suicidal behavior among adult and child & adolescent psychiatric inpatients, has been compared with each other, to assess their resemblances or variances, in a non-western, local patient population.

Methods: Five acute academic wards, which have been specified for admission of first episode adult psychiatric patients, and five acute non-academic wards, which have been specified for admission of recurrent episode adult psychiatric patients, had been selected for current study. In addition, child & adolescent section of Razi psychiatric hospital was the field of appraisal concerning its specific age-group. All inpatients with suicidal behavior (successful suicide and attempted suicide, in total), during the last five years (2013-2018), had been included in the present investigation. Besides, clinical diagnosis was based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition. Intra-group and between-group analyses had been performed by ‘comparison of proportions’. Statistical significance as well, had been defined as p value ≤0.05.

Results: As said by results, during a sixty months period, sixty-three suicidal behaviors among adult patients, including one successful suicide and sixty-two suicide attempts, and fourteen suicide attempts among child & adolescent patients, without any successful one, had been recorded by the security board of the hospital. While among adults and child & adolescent patients no significant gender-based difference was evident, with respect to suicidal conduct, among adults, the most frequent mental illness was bipolar I disorder, which was significantly more prevalent in comparison with other mental disorders. The other disorders included schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, personality disorders (borderline & antisocial), substance abuse disorders, and adjustment disorder. Among child & adolescent subjects, the most frequent mental illness was, once more, bipolar I disorder, followed by conduct disorder, and substance abuse disorder. Moreover, no significant difference was evident between the first admission and recurrent admission cases in adults or child & adolescents. While self-mutilation, self poisoning and hanging were the preferred methods of suicide among both groups, self-mutilation was significantly more prevalent than the other ways.

Conclusion: While the annual incidence of suicidal behavior in inpatient adults and child & adolescents was comparable, bipolar disorder was the most frequent serious mental illness among suicidal subjects of both groups. Moreover, self-mutilation was the preferred method of suicide in adult and child & adolescent psychiatric inpatients.

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders; Suicide; Suicide Attempt; First Admission; Recurrent Admission; Schizophrenia; Bipolar Disorder; Depression; Substance Abuse Disorder

Introduction

In psychiatry, suicide is the primary emergency, with homicide and failure to diagnose an underlying potentially fatal sickness representing other, less common psychiatric emergencies [1]. It is estimated that there is a 25 to 1 ratio between suicide attempts and completed suicides [2]. Although significant shifts were seen in the suicide death rates for certain subpopulations throughout the past century [3], suicide is presently ranked the tenth general cause of death in the United States [4]. On the other hand, almost 95 percent of all persons who commit or attempt suicide have a diagnosed mental disorder. In this regard, persons with delusional depression are at highest risk of suicide [5]. So, psychiatric patients’ risk for suicide is 3 to 12 times that of non-patients. For male and female outpatients who have never been admitted to a hospital for psychiatric treatment, the suicide risks are three and four times greater, respectively, than those of their counterparts in the general population [6,7]. A past suicide attempt is perhaps the best indicator that a patient is at increased risk of suicide [8]. Moreover, while in the United States, suicide is the third leading cause of death among adolescents, after accidental death and homicide, a young child is hardly capable of planning and carrying out a genuine suicide plan [9]. Therefore, cognitive immaturity seems to play a protective role in preventing even children who wish they were dead from committing suicide [10]. Additional risk factors in suicide include a family history of suicidal behavior, exposure to family violence, impulsivity, substance abuse, and availability of lethal methods [11]. High levels of hopelessness, poor problem-solving skills, and a history of aggressive behavior, too, are risk factors for suicide [11]. Risk factors for suicide are both individual and familial. Suicidal behaviors aggregate in families, and family history of suicidal behaviors is an independent risk factor for suicide attempts and completed suicides [12]. In the context of suicide, there is a growing body of evidence showing that exposure to early-life maltreatment can affect molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of behavior through methylation and histone modification, supposed to induce behavioral abnormalities during the early development, and possibly later in life, affect genes involved in crucial neural processes. This mechanism is called epigenetics [13]. Childhood abuse and other negative environmental factors seem to target the epigenetic regulation of genes involved in the synthesis of neurotrophic factors and neurotransmission [14]. Psychological characteristics that differentiate adolescent suicide attempters from psychiatrically disorder comparison groups include impulsivity, impulsive aggression (the tendency to respond to frustration or provocation with hostility or aggression), and cognitive bias and attraction to suicide [15,16]. Youth otherwise at high risk, namely those with a history of abuse, are protected against suicidal risk by having a prosocial peer group and youth who have a strong connection to school, even in the face of other risk factors, experience some protection from suicidal risk [17]. While as regards the comparison between adults’ and child & adolescents’ suicidal behavior, scarceness of study is noticeable, some of scholars believe that the frequent practice of combining adult and adolescent suicide and suicide behavior findings can result in misleading conclusions [18]. On the other hand, some of researchers have stated that, while not totally dissimilar, suicidal behavior may be a different phenomenon in adolescents than in adults [19,20]. Hence, in the present study, the clinical profile of suicidal behavior among adult and child & adolescent psychiatric inpatients, has been compared with each other, to assess their resemblances or variances, in a nonwestern, local patient population.

Methods

Razi psychiatric hospital, as the largest psychiatric hospital in the middle east, which is located in south of capital city of Tehran, with a capacity around 1375 active beds, had been selected as the field of study in the present assessment. Amongst its separate existent sections, five acute academic wards, which have been specified for admission of first episode adult psychiatric patients, and five acute non-academic wards, which have been specified for admission of recurrent episode adult psychiatric patients, with a collective capacity around two hundred active beds in each cluster ( four hundreds beds, totally), had been selected for current study. Among the aforesaid academic divisions, two wards included female inpatients, with around eighty beds, and the remaining three wards included male inpatients. All non-academic wards involved male inpatients. In addition, child & adolescent section of Razi psychiatric hospital was the field of appraisal concerning its specific age-group. For evaluation, all inpatients with suicidal behavior (successful suicide and attempted suicide, in total), during the last sixty months, had been included in the present investigation. Besides, clinical diagnosis was based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) [21].

Statistical Analyses

Intra-group and between-group analyses had been performed by ‘comparison of proportions’. Statistical significance as well, had been defined as p value ≤0.05. MedCalc Statistical Software version 15.2 was used as statistical software tool for analysis.

Results

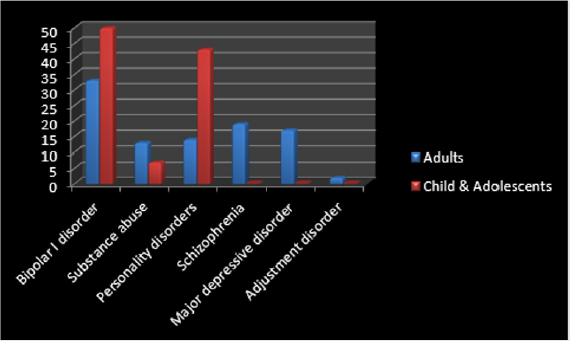

As said by results, among 19160 adult psychiatric patients and 748 child & adolescent psychiatric patients hospitalized in Razi psychiatric hospital, during a sixty months period (2013-2018), sixty-three suicidal behaviors among adult patients, including one successful suicide and sixty-two suicide attempts, and fourteen suicide attempts among child & adolescent patients, without any successful one, had been recorded by the security board of the hospital (Table 1). While among adults, male and female subjects included thirty-three and thirty patients, respectively, six and eight of suicide subjects among child & adolescent patients included male and female patients, correspondingly. Incidentally, no significant gender-based difference, as well, was evident, with respect to suicidal conduct (Table 2). Among adults, the most frequent mental illness was bipolar I disorder (34.92%), which was significantly more prevalent in comparison with other mental disorders (p<0.04, p<0.02, p<0.007, and p<0.003 in comparison with schizophrenia, depression, personality disorders and substance abuse, respectively). The other disorders included schizophrenia (19.04%), major depressive disorder (MDD) (17.46%), personality disorders (borderline & antisocial) (14.28%), substance abuse disorders, especially methamphetamine induced psychosis (MIP) (12.69%), and adjustment disorder (1.58%) [22,23]. Among child & adolescent patients, the most frequent mental illness was, once more, bipolar I disorder (50%), followed by conduct disorder (42.85%), and substance abuse disorder (7.14%) (Figure1). In this regard, while no significant difference was evident between the first two primary psychiatric disorders (Table 3), bipolar disorder was significantly more prevalent among female adolescents (z=2.72, p<0.007, CI 95%:0.19, 1.23). Moreover, while the annual incidences of suicidal behavior were around 0.035% and 0.030%, in the first admission and recurrent admission adult inpatients, respectively, and 0.21% and 0.16%, in the first admission and recurrent admission child and adolescent inpatients, in turn, no significant difference was evident between the first admission and recurrent admission cases in adults (p<0.31) or child & adolescents (p<0.44) (Table 1) [24]. Between-group analysis, as well, did not show any significant difference, quantitatively, between two groups, with respect to the aforesaid variables (z = 0.21, p<0.82, CI 95%: -0.25, 0.32, regarding fist admissions and recurrent admissions, in that order). While self-mutilation, self-poisoning and hanging were the preferred methods of suicide among 61.11%, 19.44% and 19.44% of adults and 60%, 20% and 20% of child and adolescents, respectively, the first style was significantly more prevalent than the other ways (Z=1.96, P<0.05, CI 95% : -0.008,0.453) [23-24]. Furthermore, although with respect to the preferred methods of suicide no significant gender-based difference was evident among adults in the present assessment, self-mutilation was significantly more prevalent among female subjects in comparison with the male subjects, in child and adolescent group (Z= 1.96 , P< 0.02, CI: -1.23,-0.10).

Table 1: Comparing suicidal behavior between first admission and recurrent admission psychiatric patients in Razi psychiatric hospital thru 2013-2018.

Table 3: Frequency of psychiatric disorders among adults’ and child & adolescents’ suicidal patients.

Discussion

The term suicidal behavior describes a spectrum of manners, including suicide attempts of varying degrees of intent and lethality, up to completed suicide [25]. Suicide occurs because of an imbalance between distress and restraint. Factors that increase distress and that decrease restraint increase imminent suicidal risk. Factors that decrease restraint include availability of a lethal means of suicide, impulsivity, alcohol and substance abuse, or feeling that people will not care or will be relieved by the person’s suicide [26]. Suicidal behavior and ideation are measured across five spheres: ‘intensity and intent’, ‘lethality’, ‘precipitant’, ‘motivation’, and ‘availability of lethal agents’ [27]. Because the majority of psychiatrically ill individuals never engage in suicidal behavior or die by suicide, the treatment of psychiatric disorder is likely to be indispensable but may not be sufficient to stop suicidal behavior [28]. Assessing suicidality contains comprehensively appraising the patient’s current presentation, as well as obtaining a detailed history [29]. The practitioner needs to identify whether the patient suffers from a psychiatric illness associated with higher suicide risk [30,31]. The presence of the diathesis, too, can be shown by a history of attempting suicide as well as by the presence of suicidal behavior in immediate family members, because suicidality has been shown to have familial/genetic associations [32]. Thus, a critical place for the practitioner to start with a suicide assessment is to assess the presence of the elements of the diathesis (pessimism/ hopelessness, aggression, and impulsivity) [33,34]. The diathesis, or predilection to suicidal conduct, includes a set of durable conditions or traits, the presence of which makes a person more probable to engage in suicidal manners when encountering a stressor, compared with someone without the diathesis [35]. Back to our discussion and according to the findings of the present study, while with respect to suicidal behavior no significant gender-based difference was evident between the aforesaid inpatient groups, Safer had found a 5:1 male/female ratio; though in his out-patiently survey adults and adolescent suicide completers were similar with respect to their gender ratio, and serious psychopathology [18]. Zitzow et al. [19] too, had found gender as a more important variable than age in their comparative analysis. Concerning prevailing psychopathology, our conclusions are once more rather similar to the findings of Safer, because bipolar I disorder was the most frequent mental disorder among suicidal adults and child & adolescents in the current assessment. Substance abuse, too, was existent in both groups with no significant difference, proportionately. On the other hand, the outcomes revealed that other serious conditions like schizophrenia or major depressive disorder could not be accounted as important causes of suicidal behavior among child & adolescents, though they were present as serious illnesses among adult patients. On the contrary, antisocial behavior was significantly more prevalent among younger age group. These variances, while displaying a dynamic developmental discrepancy with respect to psychopathology, demands further innovative age-specific studies and managements. Thus, such an attitude may not be in harmony with the viewpoint of Safer, who believed that combining adult and adolescent suicidal behavior findings can result in misleading conclusions [18]. Also, our result concerning relationship between suicidal demeanor and earlier hospitalization was not rather in agreement with the conclusions of Safer, who had found that the suicide outcome following psychiatric hospitalization is eightfold greater in adults than in youths, and adolescents differed from adults in suicidal behavior in their greater attempt rate, higher attempt/completion ratio, and lower rates of short and intermediate completion following psychiatric treatment [18]. As said by our results, no significant difference was evident between the first admission and recurrent admission cases in adults or child & adolescents, which was once more valid in between-group analysis. Also, with respect to suicidal techniques or devices, our discoveries was not in harmony with the outcomes of Parellada et al. [20] who had found that adolescents use significantly more poisoning approaches and may display more impulsive and less lethal directed behavior than adults. As stated by our conclusions, while self-mutilation, self poisoning and hanging were the preferred methods of suicide among both groups, the first style was significantly more prevalent than the other methods. Meanwhile, in child & adolescent group, self-mutilation was significantly more prevalent among female subjects in comparison with the male subjects, which could reveal a gender-based preference.

Anyhow, though many suicide risk assessment tools have been developed over the years, and many practitioners prefer a rating scale that places the patient at mild, moderate, or maximum risk, the inherent fault with such apparatuses is that the patient is most likely in a dynamic, not static, situation, of which the current situation of potential impending inpatient admission can actually change the risk at any moment [35]. In suicide prevention, policies can be directed toward health care services or at the general population. The health care stratagem aims at recognizing risk groups, improving diagnostics, treatment, and offering better rehabilitation for suicidal patients. Health care interventions can be selective and target subgroups displaying risk factors for suicide [33]. Protective factors for suicide include cognitive flexibility, active coping strategies in difficult life situations, healthy lifestyles, active social networks, confidence and the sense of personal value, and the ability to seek advice from others and help from the health care system for subsequent treatment [34]. Organizing home visits, case management, and regular telephone contacts with susceptible persons are effective preventive methods, as it diminishes isolation and provides the opportunity to early detect risk factors and risk situations for suicide. Absence of post- discharge following program, deficiency of documented data regarding the suicidal behavior or its idea before admission, were among the weaknesses of the present assessment. In spite of remarkable findings of the current study, more methodical and comprehensive investigations in future can improve the quality and amendment of mental health services for proper response to this vital problem.

Conclusion

While the annual incidence of suicidal behavior in inpatient adults and child & adolescents was comparable, bipolar disorder was the most frequent serious mental illness among suicidal subjects of both groups. Moreover, self-mutilation was the preferred method of suicide in adult and child & adolescent psychiatric inpatients.

Acknowledgement

The author gratefully acknowledges Memari A, Rezaie M and Hamidi M for their precious assist and support of the study.

References

- Hall WD (2006) How have the SSRI antidepressants affected suicide risk? Lancet 367(9527): 1959-1962.

- Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson N (2009) Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: Findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med 6: 1-13.

- Kaess M, Parzer P, Haffner J (2011) Explaining gender differences in non-fatal suicidal behavior among adolescents: A population-based study. BMC Pub Health pp. 597-603.

- March J, Silva S, Petrycki S (2007) The TADS Team. The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): Long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 1132-1143.

- Newton AS, Hamm MP, Bethell J, Rhodes AE, Bryan CJ, et al. (2010) Pediatric suicide-related presentations: A systematic review of mental health care in the emergency room department. Ann Emerg Med 56: 649-659.

- Christiansen E, Larsen KJ (2011) Young people's risk of suicide attempts after contact with a psychiatric department-A nested case-control design using Danish register data. J Child Psycho I Psychiatry 52: 102.

- Field T (2011) Prenatal depression effects on early development: A review. Infant Behav Dev 34(1): 1-14.

- Olfson M, Shafefer D, Marcus SC, Greenberg T (2003) Relationship between antidepressant medication treatment and suicide in adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60(10): 978-982.

- Wagner KD, Brent DA (2009) Depressive disorders and suicide in children and adolescents. In: Sadock BJ, et al. (eds.) Kaplan & Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. (9th ) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, USA 2: 3652.

- Zalsman G (2010) Timing is critical: Gene, environment and timing interactions in genetics of suicide in children and adolescents. Eur Psychiatry 25: 284-286.

- Gould MS, Greenberg T, Velting DM, Shafefer D (2003) Youth suicide risk and preventive interventions: A review of the past ten years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 42(4): 386-405.

- Apter A, Gvion Y (2016) Adolescent suicide and attempted suicide. In: Wasserman D (ed.) Suicide: An Unnecessary Death. (2nd ) Oxford University Press, London, UK.

- Brent DA, Melhem N (2008) Familial transmission of suicidal behavior. Psychiatr Clin North Am 31(2): 157-177.

- Wasserman D, Rihmer Z, Rujescu D (2012) The European Psychiatric Association (EPA) guidance on suicide treatment and prevention. Eur Psychiatry 27(2): 129-141.

- World Health Organization (2014) Preventing Suicide: A Global Imperative. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Nock MK, Banaji MR (2007) Prediction of suicide ideation and attempts among adolescents using a brief performance-based test. J Consult Clin Psychol 75(5): 707-715.

- Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D (2015) Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry 54(2): 77-102.

- Safer D (1997) Adolescent/Adult Differences in Suicidal Behavior and Outcome. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 9 (1): 61- 66.

- Zitzow D, Desjarlait F A study of suicide attempts comparing adolescents to adults on a northern plain. American Indian Reservation 4: 35-69.

- Parellada M, Saiz P, Moreno D (2008) Is attempted suicide different in adolescent and adults? Psychiatry Res 157(1-3): 131-137.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA) (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (5th edn.) American Psychiatric Association, Washington DC, USA pp. 31-715.

- Shoja Shafti S, Memarie A, Rezaie M, Hamidi M (2019) Suicides and Suicide Attempts Among Psychiatric Hospital Inpatients in Iran. Current Psychiatry Research and Reviews 15 (3): 215 - 222.

- Shoja Shafti S, Memarie A, Rezaie M, Hamidi M (2019) Suicide among Adult Psychiatric Inpatients-A Pilot Study in Iran. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research 20 (5): 15448-15454.

- Shoja Shafti S, Memarie A, Rezaie M, Hamidi M (2019) Clinical Profile of Suicide among Adolescent Psychiatric Inpatients in Iran. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research 18 (1): 13242-13246

- Leadholm AK, Rothschild AJ, Nielsen J, Bech P, Ostergaard SD (2014) Risk factors for suicide among 34,671 patients with psychotic and non-psychotic severe depression. J Affect Disord 156: 119-125.

- Bridge JA, Goldstein TR, Brent DA (2006) Adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47(3-4): 372-394.

- Bridge JA, Mc Bee Strayer SM, Cannon EA (2012) Impaired decision making in adolescent suicide attempters. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 51(4): 394-403.

- Wasserman D, Hoven CW, Wasserman C (2015) School-based suicide prevention programmes. The SEYLE cluster-randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 385(9977): 1536-1544.

- Carli V, Hoven CW, Wasserman C (2014) A newly identified group of adolescents at “invisible” risk for psychopathology and suicidal behavior: Findings from the SEYLE study. World Psychiatry 13(1): 78-86.

- Chesin M, Yuryev A, Stanley B (2015) Psychological treatments for suicidal individuals. In: Wasserman D (ed.) Suicide: An Unnecessary Death. (2nd ) Oxford University Press, London, UK.

- Novick DM, Swartz HA, Frank E (2010) Suicide attempts in bipolar I and bipolar II disorder: A review and meta-analysis of the evidence. Bipolar Disord 12(1): 1-9.

- Sokolowski M, Wasserman J, Wasserman D (2015) An overview of the neurobiology of suicidal behaviors as one meta-system. Mol Psychiatry 20(1): 56-71.

- Mann JJ, Currier D (2007) Prevention of suicide. Psychiatr Ann 37: 331-336.

- Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, (2002) Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. National Academic Press, Washington DC, USA.

- Jacobs D, Gutheil TG (1996) Guidelines for Suicidality. Risk Management Foundation of the Harvard Medical Institutions Cambridge, USA, pp. 1-45.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...