Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-5945

Case Report(ISSN: 2638-5945)

Small Bowel Intussusception Secondary to Metastatic Spindle Cell Sarcoma: A Case Report and Review of the Literature Volume 3 - Issue 3

Tina W Wong1*, Debra A Wong2, Hashem Ayyad3, David Row1, Ronald A Gagliano1, and James Mankin1

- 1Department of Surgery, Creighton University School of Medicine Phoenix, USA

- 2Department of Oncology, University of Arizona Cancer Center, USA

- 3Department of Pathology, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, USA

Received:January 02, 2020 Published: January 10, 2020

Corresponding author: Tina W Wong, Department of Surgery, Creighton University School of Medicine Phoenix, Maricopa Medical Center, 2601 E Roosevelt Street, Phoenix, AZ 85008, USA

DOI: 10.32474/OAJOM.2020.03.000164

Abstract

Background: Intussusception is an uncommon diagnosis in adults. It is characterized by an abnormal luminal “lead point” that precipitates bowel invagination, resulting in obstructive symptoms that warrants further investigation. Both benign and malignant tumors have been reported to cause small bowel intussusception, with primary small bowel malignancies occurring more commonly. We present an unusual case of a middle-aged gentleman with small bowel intussusception and obstruction caused by a metastatic spindle cell sarcoma and a review of the available literature.

Case Presentation: A 50-year-old male patient with a history of recurrent spindle cell sarcoma of the scalp treated 3 years prior presented with abdominal pain and bloating. Diagnostic workup revealed two segments of small bowel intussusception and obstruction as well as several lung nodules. The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy for resection and primary anastomosis of the intussuscepted segments of small bowel. Histologic analysis of the surgical specimens confirmed metastatic spindle cell sarcoma. After completion of full metastatic workup, patient was counseled on the diagnosis and offered palliative chemotherapy while awaiting results from tumor molecular profiling to guide future treatment and clinical trial options.

Conclusion: Intussusception in the adult patient should be carefully evaluated, with a high suspicion for malignancy as the underlying cause, especially in those with a personal history of cancer.

Keywords: Intussusception; Sarcoma; Spindle Cell

List of Abbreviations: CT: Computed Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; PET: Positron Emission Tomography; FDG: Fluorodeoxyglucose; NET: Neuroendocrine Tumor; GIST: Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor; UPS: Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma; RMS: Rhabdomyosarcoma; LS: Liposarcoma; AS: Angiosarcoma; ES: Ewing Sarcoma; FS: Fibrosarcoma; OS: Osteosarcoma; CS: Chondrosarcoma; IDCS: Interdigitating Dendritic Cell Sarcoma; ASPS: Alveolar Soft Part Sarcoma; LMS: Leiomyosarcoma; MFH: Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma; LCS: Lung Carcinosarcoma; MS: Melanosarcoma; KS: Kaposi Sarcoma; RCS: Round-Celled Sarcoma; SCS: Spindle Cell Sarcoma; H&E: Hematoxylin And Eosin

Introduction

Intussusception of the small or large intestine is defined by the telescoping of a segment of bowel on itself, with the “donor” invaginated segment termed “intussusceptum” and the “recipient” segment termed “intussuscipien” [1]. The majority of intussusception is associated with a lead point from which the telescoping begins, such as enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes or tumor. While intussusception is a common phenomenon in the pediatric population and most often of benign etiology, its occurrence in the adult may be the first sign of malignancy and warrants further investigation [1-3]. Here we describe a case of a recurrent spindle cell sarcoma with metastases to the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in jejunal intussusception 3 years after initial treatment of the primary lesion.

Case Presentation

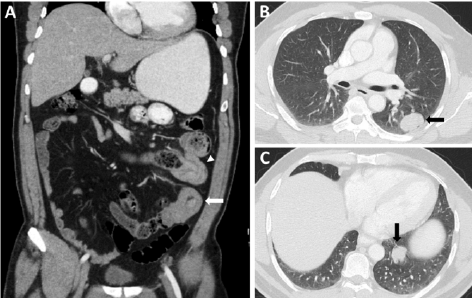

A 50-year-old man presented to the Emergency Department with acute-onset severe left-sided abdominal pain and associated bloating. On examination, his abdomen was moderately distended and tender to palpation in the setting of normal vital signs. The patient’s past medical history was significant for spindle cell sarcoma of the frontal scalp diagnosed and excised three years prior. Pathology of the excised scalp mass was consistent with high-grade spindle cell sarcoma with a high mitotic rate and tumor extension to <1mm from the surgical margin. The patient thus underwent re-resection of the close margin followed by adjuvant radiation therapy. Two years later, the patient was noted to have a progressive growth around the surgical scar. Excisional biopsy confirmed recurrent spindle cell sarcoma with positive margins. Subsequent re-excision was performed without further adjuvant treatment. In the Emergency Department, a complete blood count and metabolic panel were normal. A computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast revealed two segments of jejunal intussusception resulting in small bowel obstruction, in addition to several lung nodules concerning for metastatic disease (Figure 1). Surgical consultation was obtained, and the patient was taken for exploratory laparotomy and small bowel resection with primary anastomoses of the two separate segments of intussuscepted small bowel. The patient’s hospital course was uncomplicated, and he was discharged home on postoperative day 3.

Figure 1: Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast demonstrates small bowel intussusception and lung nodules. (A) Two segments of jejunum with radiographic finding of invagination (white arrowhead) and target sign (white arrow), indicative of intussusception. Distended stomach and moderately dilated small bowel are seen proximal to the intussusception without passage of oral contrast through this region, consistent with small bowel obstruction. (B-C) Solid pulmonary nodules with irregular borders (black arrows) within the left chest, concerning for metastatic disease.

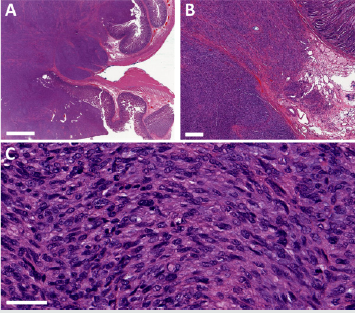

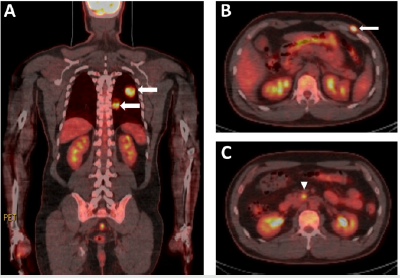

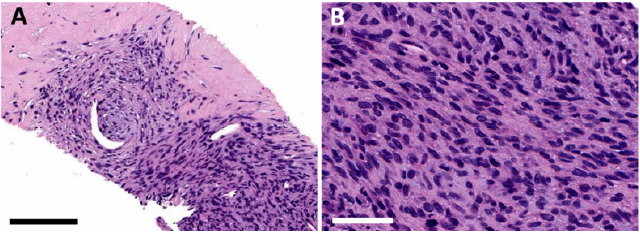

At his 2-week follow-up in surgery clinic, the patient was found to be recovering well. By that time, surgical pathology was finalized, after thorough analysis and expert consultation. The resected proximal small bowel revealed a 4.5 cm neoplasm and a second neoplasm also measuring 4.5 cm was seen in the distal small bowel. Both tumors were composed of moderately atypical spindle cells arranged in intersecting fascicles, with focally myxoid and collagenous stroma (Figure 2). Mitotic activity was greater than 30/HPF. Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD34 and CD99, and negative for pancytokeratin, S100, CD117, DOG1, desmin, SOX10, calretinin, BCL-2, HMB45, smooth muscle actin, STAT6, ALK-1, and ERG. MDM2 was positive only in scattered nuclei. Ki-67 proliferation index was 15-20 percent. Collectively, these findings were consistent with recurrent metastatic high-grade (FNCLCC grade 3) malignant spindle cell sarcoma. Consultation with medical oncology was obtained. The patient underwent staging imaging with a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with and without gadolinium, which showed no locally recurrent or intracranial disease. Whole body positron emission tomography (PET)-CT revealed several fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid lesions in the left lung and chest wall as well as multiple periportal and pericaval enlarged lymph nodes (Figure 3). CT-guided biopsy of an intrathoracic lesion confirmed metastatic spindle cell sarcoma (Figure 4). Next-generation sequencing tumor molecular profiling is being pursued to help guide future treatment strategies and clinical trial options. The patient, who maintains an excellent performance status, has been counseled on palliative doxorubicin and ifosfamidebased chemotherapy, which he is eager to commence.

Figure 2: Histologic examination of surgical specimen reveals metastatic spindle cell sarcoma to the small bowel. Formalinfixed paraffin-embedded tissue was sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), demonstrating atypical spindle cells with focally myxoid and collagenous stroma. (A) Low magnification, scale bar = 3 mm. (B) Medium magnification, scale bar = 600 μm. (B) High magnification, scale bar = 50 μm.

Figure 3: Whole body PET-CT reveals FDG-avid lesions in the left lung (A; thick white arrows) and left chest wall (B; thin white arrow) as well as FDG-avid enlarged pericaval lymph node (C; white arrowhead), suggestive of metastatic disease.

Figure 4: Core needle biopsy of intrathoracic lesion demonstrates malignant appearing spindle-shaped cells, confirming metastatic spindle cell sarcoma. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue was sectioned and stained with H&E. (A) Medium magnification, scale bar = 150 μm. (B) High magnification, scale bar = 50 μm.

Discussion

Intussusception is an uncommon diagnosis in adults. Although physiologic intussusception can occur with hyperdynamic peristalsis of the intestines, such as in the setting of gastroenteritis, when combined with obstructive symptoms, intussusception in an adult patient suggests an ominous etiology, and a pathologic lead point is associated 70-90% of the time [1,2]. Management of intussusception in adults differs from that in the pediatric population. Specifically, in adults, surgical resection of the involved bowel is recommended rather than simple reduction (either via pneumatic/hydrostatic enema or operatively) [3]. Clinical suspicion for a neoplastic process was high in our patient, given his history of soft tissue sarcoma of the scalp and the concurrent finding of lung nodules on his imaging. Our patient thus underwent laparotomy and multi-segment small bowel resection, and pathologic analysis of the surgical specimen confirmed recurrent metastatic spindle cell sarcoma. Spindle cell sarcoma is a subset of soft tissue sarcoma that encompasses a myriad of histologic subtypes. While all subtypes are of mesenchymal origin, more than 50 subtypes of soft tissue sarcomas exist, each with variable degree of differentiation, recurrence rates, and metastatic potential. In general, sarcomas can be classified based on the cell-lineage they resemble (e.g., smooth muscle, fibroblast, adipocyte, bone, etc.). Not uncommonly, however, the irregularity and degree of dedifferentiation of the tumor cells make determination of cell-lineage impossible; these tumors are thus named based on their morphologic appearance [4]. Spindle cell sarcoma, for example, is characterized by its long, narrow, spindle-like appearance microscopically.

Soft tissue sarcomas, including spindle cell sarcomas, are typically diagnosed at an early stage, with less than 15% with metastatic disease at presentation [5]. However, given the aggressive nature of these tumors, approximately one-third of patients with localized soft tissue sarcoma will develop metastatic disease within 5 years, despite adequate initial treatment. Overall survival in patients with soft tissue sarcoma correlates with the stage of the disease, with an approximately 60% 5-year survival rate for localized disease but only 15% for those with distant metastases [6]. Lung is the primary site for distant metastases, but other common sites of metastases include bone, liver, brain, and lymph nodes [5]. The small intestine is an extremely rare location for sarcoma metastasis. Review of the literature reveals only 46 case reports of various subtypes of bone or soft tissue sarcoma with metastases to the small bowel. Of these, 30 patients presented with small bowel intussusception (with or without obstruction) secondary to the metastatic lesion [7-36]. Other clinical findings that led to the diagnosis of metastatic sarcoma have included obstruction without intussusception (n=6) [37-42] gastrointestinal bleeding (n=10) [11-46], and bowel perforation (n=6) [37-51]. In one report, metastatic sarcoma to small bowel was found incidentally on imaging in an asymptomatic patient [52]. The most common types of sarcoma reported to have metastasized to the small bowel include osteosarcoma (n=12), angiosarcoma (n=5), rhabdomyosarcoma (n=5), liposarcoma (n=4), and leiomyosarcoma (n=4) (Table 1).Overall, neoplasms of the small bowel are rare, with the majority being benign lesions (e.g. lipoma, leiomyoma, fibroma, hamartoma, or ectopic gastric or pancreatic tissue). Of all the cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, those found within the small bowel account for only 1-3% [53,54]. Malignancies of the small bowel are most often primary (e.g. adenocarcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), neuroendocrine tumor (NET), or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma) [55]; however, metastases from extra-abdominal sites have also been reported. Melanoma represents the most common metastatic tumor to the small bowel, accounting for over 50% [53]. Other cancers with a propensity for small bowel metastases include invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast, adenocarcinoma of the lung, and clear cell carcinoma of the kidney. As demonstrated in our case, metastases from a primary cutaneous spindle cell sarcoma to the small bowel can occur and cause intussusception, but our literature review shows that it is an exceedingly rare problem.

Table 1: Review of the literature – case reports of metastatic bone or soft tissue sarcoma to the small bowel.

Conclusion

This is an unusual case of an adult patient with metastatic spindle cell sarcoma to the small bowel who presented with intussusception and bowel obstruction. The case highlights the importance of careful evaluation and workup of intussusception in the adult patient population. The clinician must have a high index of suspicion for underlying malignancy, and the appropriate surgical management should be undertaken with this in mind. Close attention should be paid to patients with a personal history or extensive family history of malignancy. As illustrated in this case, expert pathologic analysis is integral to establishing an accurate diagnosis and prognosis. Early involvement of the appropriate specialists is recommended whenever cancer is suspected, to help achieve the best possible outcomes for patients via a multidisciplinary approach.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Conflict of Interest

- Azar T, Berger DL (1997) Adult intussusception. Ann Surg 226(2): 134-138.

- Marinis A, Yiallourou A, Samanides L, Dafnios N, Anastasopoulos G, et al. (2009) Intussusception of the bowel in adults: a review. World J Gastroenterol 15(4): 407-411.

- Marsicovetere P, Ivatury SJ, White B, Holubar SD (2017) Intestinal Intussusception: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 30(1): 30-39.

- Cloutier JM, Charville GW (2019) Diagnostic classification of soft tissue malignancies: A review and update from a surgical pathology perspective. Curr Probl Cancer 43(4): 250-272.

- Bui NQ, Wang DS, Hiniker SM (2019) Contemporary management of metastatic soft tissue sarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer 43(4): 289-299.

- Abaricia S, Van Tine BA (2019) Management of localized extremity and retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma. Curr Probl Cancer 43(4): 273-282.

- Sun KK, Shen XJ (2019) Small bowel metastasis from pulmonary rhabdomyosarcoma causing intussusception: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol 19(1): 71.

- Xi S, Tong W (2018) Pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma metastasis to small intestine causing intussusception: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 97(51): e13648.

- Gys B, Peeters D, Driessen A, Snoeckx A, Komen N (2016) Adult suprapatellar pleiomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma with jejunal metastasis causing intussusception: a case report. Acta Chir Belg 116(6): 376-378.

- Tan QT, Teo JY, Ahmed SS, Chung AY (2016) A case of small bowel metastasis from spinal Ewing sarcoma causing intussusception in an adult female. World J Surg Oncol 14: 109.

- Esfehani MH, Mahmoodzadeh H, Omranipour R (2015) Small intestine and ovarian metastasis in a patient with a history of cardiac fibrosacoma. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst 27(3): 171-172.

- Kuwabara H, Fujita K, Yuki M, Goto I, Hanafusa T, et al. (2014) Cytokeratin-positive rib osteosarcoma metastasizing to the small intestine. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 57(1): 109-112.

- Abbo O, Pinnagoda K, Micol LA, Beck-Popovic M, Joseph JM (2013) Osteosarcoma metastasis causing ileo-ileal intussusception. World J Surg Oncol 11(1): 188.

- Bustinza Linares E, Socola F, Ernani V, Miller SA, Trent JC (2012) Extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma with small bowel metastasis causing bowel obstruction. Case Rep Oncol Med 2012: 621025.

- Lee GW, Kim TH, Min HJ, Kim HJ, Jung WT, et al. (2010) Unusual gastrointestinal metastases from an alveolar soft part sarcoma. Dig Endosc 22(2): 137-139.

- Weiss JM, Attia S, Bailey HH, Weber S, Hu J, et al. (2010) Metastatic soft tissue sarcoma diagnosed by small bowel video capsule endoscopy. J Clin Oncol 28(15): e233-5.

- Shibata Y, Sato K, Kodama M, Nanjyo H (2008) Metastatic liposarcoma in the jejunum causing intussusception: report of a case. Surg Today 38(12): 1129-1132.

- Sabel MS, Gibbs JF, Litwin A, McGrath B, Kraybill WB, et al. (2001) Alveolar soft part sarcoma metastatic to small bowel mucosa causing polyposis and intussuseption. Sarcoma 5(3): 133-137.

- Horiuchi A, Watanabe Y, Yoshida M, Yamamoto Y, Kawachi K (2007) Metastatic osteosarcoma in the jejunum with intussusception: report of a case. Surg Today 37(5): 440-442.

- Kamo R, Ishina K, Hirata C, Doi K, Nakanishi T, et al. (2005) A case of ileoileal intussusception caused by metastatic pedunculated tumor of cutaneous angiosarcoma. J Dermatol 32(8): 638-640.

- Monjazeb A, Stanton C, Levine EA (2004) Intussusception secondary to metastasis from a low-grade retroperitoneal liposarcoma. Am Surg 70(9): 775-778.

- Chandramohan K, Somanathan T, Kusumakumary P, Balagopal PG, Pandey M (2003) Metastatic osteosarcoma causing intussusception. J Pediatr Surg 38(10): E1-3.

- Wootton Gorges SL, Stein Wexler R, West DC (2003) Metastatic osteosarcoma to the small bowel with resultant intussusception: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Radiol 33(12): 890-892.

- Hung GY, Chiou T, Hsieh YL, Yang MH, Chen WY (2001) Intestinal metastasis causing intussusception in a patient treated for osteosarcoma with history of multiple metastases: a case report. Jpn J Clin Oncol 31(4): 165-167.

- Okada DH, Walts AE (2000) Pathologic quiz case: dual intussusceptions in the small intestine. Metastatic leiomyosarcoma as the cause of dual intussusceotions. Arch Pathol Lab Med 124(1): 169-170.

- Ganguli SN, Hamilton P, Hanna S, Morava Protzner I (1999) Small bowel intussusception secondary to osteogenic sarcoma metastasis: case report. Can Assoc Radiol J 50(3): 170-172.

- Kanoh T, Shirai Y, Wakai T, Hatakeyama K (1998) Malignant fibrous histiocytoma metastases to the small intestine and colon presenting as an intussusception. Am J Gastroenterol 93(12): 2594-2595.

- Gorman RC, Jardines L, Brooks JJ, Daly JM (1993) Enteroenteric intussusception due to a metastatic malignant fibrous histiocytoma. J Surg Oncol 54(3): 203-205.

- Gerst PH, Levy J, Swaminathan K, Kshettry V, Albu E (1993) Metastatic leiomyosarcoma of the uterus: unusual presentation of a case with late endobronchial and small bowel metastases. Gynecol Oncol 49(2): 271-275.

- Eng J, Sabanathan S (1992) Carcinosarcoma of the lung with gastrointestinal metastasis. Case report. Scand J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 26(2):161-162.

- Sondenaa K, Soreide JA, Erichsen C, Breivik K, Heikkila R, et al. (1192) Metastases in the small intestine from a subcutaneous lower limb leiomyosarcoma. Acta Oncol 31(8): 865-866.

- Mozes M, Mozes G, Greiff M, Sacks M (1988) Metastatic osteogenic sarcoma of small intestine with intussusception. Isr J Med Sci 24(8): 426-468.

- Webster VJ, Arons I (1987) Intussusception secondary to osteogenic sarcoma metastasis. Br J Clin Pract 41(2): 628-629.

- Kehoe J, Shafir M, Rosenblum M (1983) Small bowel intussusception by metastatic chondrosarcoma: a case report. J Surg Oncol 23(3): 198-200.

- Goldberg SL, Fink V, Goldsmith B (1963) Metastatic osteogenic sarcoma of the ileum. Intussusception and intestinal obstruction. Arch Surg 86: 233-234.

- Oldfield MC, Wilson G (1959) Jejunojejunal intussusception from secondary fibrosarcoma. Br J Surg 47: 99-100.

- Plestina S, Librenjak N, Marusic A, Batelja Vuletic L, Janevski Z, et al. (2019) An extremely rare primary sarcoma of the lung with peritoneal and small bowel metastases: a case report. World J Surg Oncol 17(1):147.

- Benis E, Szilagyi A, Izbeki F, Varga I, Altorjay A (2014) [Intestinal bleeding and obstruction in the small intestine caused by metastatic thyroid angiosarcoma. Case report]. Orv Hetil 155(23): 918-921.

- Panizo Santos A, Sola I, Lozano M, de Alava E, Pardo J (2000) Metastatic osteosarcoma presenting as a small-bowel polyp. A case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 124(11): 1682-1684.

- Nagawa H, Tsuno N, Saito H, Muto T (1993) Ileal obstruction due to metastatic liposarcoma: a case report. Gastroenterol Jpn 28(5): 706-711.

- Avagnina A, Elsner B, De Marco L, Bracco AN, Nazar J, et al. (1984) Pulmonary rhabdomyosarcoma with isolated small bowel metastasis. A report of a case with immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Cancer 53(9): 1948-1951.

- Michael MA (1955) Intestinal obstruction due to metastatic melanotic sarcoma nine years after removal of primary tumor. Va Med Mon 82(4): 190-192.

- Fleetwood VA, Harris JC, Luu MB (2016) Cutaneous angiosarcoma metastatic to small bowel with nodal involvement. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 9(4): 340-342.

- Chiang KC, Yeh CN, Shih HN, Jan YY, Chen MF (2006) Lower gastrointestinal bleeding due to small bowel metastasis from leiomyosarcoma in the tibia. Chang Gung Med J 29(4): 430-444.

- Hsu JT, Lin CY, Wu TJ, Chen HM, Hwang TL, et al. (2005) Splenic angiosarcoma metastasis to small bowel presented with gastrointestinal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 11(41): 6560-6562.

- Costa A, Fustaino L, Mosca F (2001) Metastatic osteosarcoma involving the colon and ileum. Gastrointest Endosc 54(1): 75.

- Mahamid A, Alfici R, Troitsa A, Anderman S, Groisman G, et al. (2011) Small intestine perforation due to metastatic uterine cervix interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma: a rare manifestation of a rare disease. Rare Tumors 3(4): e46.

- Ruffolo C, Angriman I, Montesco MC, Scarpa M, Polese L, et al. (2005) Unusual cause of small bowel perforation: metastasis of a subcutaneous angiosarcoma of the head. Int J Colorectal Dis. 20(6): 551-552.

- Ise N, Kotanagi H, Morii M, Yasui O, Ito M, et al. (2001) Small bowel perforation caused by metastasis from an extra-abdominal malignancy: report of three cases. Surg Today 31(4): 358-362.

- Mitchell N, Feder IA (1949) Kaposi's sarcoma with secondary involvement of the jejunum, perforation and peritonitis. Ann Intern Med 31(2): 324-339.

- Waring H (1930) Secondary Sarcoma of Small Intestine. Proc R Soc Med 23(7): 939.

- Rowe SP, Coquia SF, Johnson PT, Fishman EK (2016) Liposarcoma metastases to the small bowel presenting as fat-density intraluminal lesions. Radiol Case Rep 11(4): 296-298.

- Kurniawan N, Ruther C, Steinbruck I, Baltes P, Hagenmuller F, et al. (2014) Tumours in the Small Bowel. Video Journal and Encyclopedia of GI Endoscopy 1: 632-655.

- Kopacova M, Rejchrt S, Bures J, Tacheci I (2013) Small intestinal tumours. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2013: 702536.

- Pourmand K, Itzkowitz SH (2016) Small Bowel Neoplasms and Polyps. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 18(5): 23.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...