Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2638-5945

Research Article(ISSN: 2638-5945)

Analysis of the Behavior of Stomach Adenocarcinomas in Asian and Non-Asian Patients Volume 3 - Issue 4

Noboru Motohashi1, Anuradha Vanam2, Jyothirmayi Vadapalli3 and Rao Gollapudi4*

- 1Medical Student, Santa Casa of São Paulo School of Medical, Brazil

- 2Department of Surgery, Santa Casa of São Paulo School of Medical Sciences, Brazil

- 3Resident of the Department of Surgery, Santa Casa of São Paulo School of Medical Sciences, Brazil

- 4Department of Pathology, Santa Casa of São Paulo School of Medical Sciences, Brazil

Received:February 14, 2020 Published: March 02, 2020

Corresponding author: Pedro Henrique Ferro de Brito - 6th year medical student, Santa Casa of São Paulo School of Medical, Brazil

DOI: 10.32474/OAJOM.2020.03.000166

Introduction

The patterns of incidence, mortality, biological, and gastric cancer location are not uniform among ethnicities around the world [1-6]. Notably, there is a disparity in such characteristics between Asians and non-Asians.7 The location of neoplasms in non-Asians has shown an increase in proximal and cardia cancers, while in Asians, they are neoplasms of non-cardia location - tumors that are generally associated with risk factors such as H. pylori, smoking and dietary aspects [1,8]. Geographical and hereditary factors also seem to be involved, since it has been shown that, despite much lower incidence, Asian immigrants (first generation) in the United States have the same pattern of incidence distribution as native Asians [7,9]. Other aspects seem worth noting. Patients of Asian origin have a younger age and a higher proportion of cases with signet ring cell histology [10].

This study aimed to make a comparison to verify whether clinical and epidemiological aspects differ between Asians and non-Asians in Brazil. This may provide tools to individualize treatment in the future.

Methods

Retrospective analysis of data acquired in a prospective data collection registration protocol was carried out. All patients (non-miscegenated), descendants of Japanese, Korean, Chinese and other East Asian countries were defined as Asians. Epidemiological, clinical, surgical and oncological data of all patients were analyzed and compared. Inclusion criteria: all patients with stomach cancer treated at the service from 1997 to 2018. For histological analysis, Lauren’s classification was used: diffuse or intestinal. Global mortality included patients who died from cancer or not, and post-operative deaths (30 days) were excluded. The maximum period of survival was not defined, and the minimum period was one year. Cases considered inoperable included: inextricability, carcinomatosis, metastatic disease, poor general condition or patient refusal. For staging, the 7th edition of the Classification of Malignant Tumors of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) was used [11]. The tumor sites were based on the Japanese Classification of gastric carcinomas and are classified into three basic regions: [12] U (upper third), M (middle third) and L (lower third); in cases of esophageal invasion, the letter E is placed, and in the case of duodenal invasion, the letter D. For tumors of the gastric esophageal junction, the word cardia (II or III) was associated with the letter U. The acronyms II or III refer to the Siewert classification for neoplasms of the gastric esophageal junction [13] Finally, in neoplasms of the remaining stomach after previous gastrostomies, the site was defined only as a stump. In these cases, only patients previously operated on the stomach for benign disease and those operated for malignant disease more than 5 years after the previous gastrectomy were considered (thus excluding stump recurrences).

Exclusion criteria

patients with non-adenocarcinoma stomach cancer and patients with non-available data. The study did not involve any risk for the patients, and, at no time, there was or will be exposure of them. For the statistical analysis, the Mann-Whitney test was used to verify differences in age and survival time between different ethnicities: Asian and non-Asian. The Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact test was used.

Results

There were no significant age differences between ethnicities. The average age of Asians was 61.7 years ± 9.25; while non-Asians had an average of 61.4 years ± 13.23 (p = 0.89). Regarding sex, among Asians, 75.6% of them were male, while among non-Asians we had 61.5% of male patients (p = 0.097). As for the histological type, the diffuse type predominated widely in both ethnicities. In Asians, we had 63.4% of patients with this histological type, while the intestinal type was 36.6% of cases. In non-Asians, the diffuse type predominated with 62.5% of cases. In Asians the unrespectability was 14.6%, while among non-Asians, this percentage was 32.8%.

Discussion

The differences between the findings regarding gastric adenocarcinomas between populations of Asian and non-Asian origin have long been discussed. Asian countries traditionally, especially Japan and South Korea, have high rates of early diagnosis and consequently better survival rates [14]. Those countries, due to their high incidence rates, perform routine screening, in Japan using contrast radiographs and in Korea using endoscopy upper digestive [15,16]. It is known that as immigrants settle in the countries, the incidence rates gradually approach those of the country in which they live and from the third generation onwards, they generally equal. Apparently, the cause is the change in eating habits, which are responsible for carcinogenesis in those groups [7]. Chen et al. [17] demonstrated in 160 patients operated in Australia that Asians were diagnosed at a younger age than non-Asians, an average of 60 years for the former and 70 for the latter. We did not observe, however, this difference in the studied population, in which age was just over 60 years for both groups. A basic difference between Chen’s study and the present study is the fact that we evaluated all patients, including those who were not operated. It is noted that the Asians in our study are similar in age to those studied in Australia, but the native Brazilians were younger than the native Australians. This could be explained by the differences in quality of life and especially food between a developed country and ours, in the process of development. The patients evaluated by us, originate in a large part of the north and northeast regions, where eating habits predisposing to carcinogenesis predominate [18]. Regarding to survival, we have a very broad analysis that includes patients at all stages and also non-operated patients. There is a tendency for better survival rates in Asians (Table 1), which also occurs in the literature in general [17]. In this study, the authors revealed a surprising difference in survival in five years (68% x 31% in five years) despite the groups being similar with regard to stadiums. We noticed in our sample, a certain predominance of stage I in Asians and stage IV in non-Asians (Table 2). The presence of metastases (M1) was also significantly higher in westerners (Table 3). Our remarkably low survival (median of 26 and 13 months) is explained by the fact that we included patients at a very advanced stage, so they were often submitted only to palliative treatments or even no type of treatment. It should be noted that survival was higher in Asians and this can be attributed to the greater number of Eastern patients in whom resection can be performed when compared to Westerners, since it is known that one of the greatest healing factors is gastrectomy. In Westerners the already known predominance of males, although noted, is less pronounced than among Orientals. This gender difference is not always noticed in other studies.10 In this regard, we wonder whether women of the second and third generations of Asian descent would not have improved their eating habits earlier than their male counterparts. It should also be highlighted here several aspects of male nutrition, especially in our environment, where the routine use of alcohol is much more noticeable in males [19]. It is known to be an aggressive factor that exposes the mucosa to more mutations. The same can be said about smoking, which is still prevalent among men [20]. The benzopyrene present in cigarettes has been known as a type I carcinogen for decades [21]. Another aspect worth mentioning is the incidence of the diffuse type, which was twice the intestinal type of Laurén in both groups (Table 4). According to the literature, the intestinal type is the most common one of adenocarcinoma, occurring in approximately 54% of cases of adenocarcinomas, while the diffuse type would occur in approximately 30% [22]. What surprised us was the fact that there was a high rate of diffuse type tumors in a developing country, since it is known that in these countries H. pylori infection is high and eating conditions are favorable to the intestinal type.

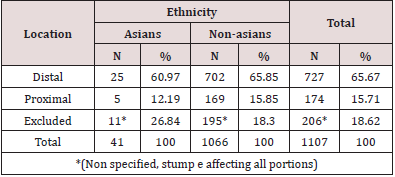

Inoperability was doubled in Western patients in our patients. In the literature, there is a tendency towards greater inoperability in non-Asian patients, this difference is even more noticeable when we look at our series of cases in which the incidence of inoperable patients is twice greater in Westerners when compared to Asians.10 We think that this fact may be related to the socio-cultural level of Asians, who in our country are, in general, more privileged in that aspect. There are reports, for example, that black populations have less access to treatment than Caucasians and Asians [23]. Regarding location, Strong et al. [24] demonstrated that both ethnicities, Asian and non-Asian, have more distal tumors (Table 5) than proximal tumors (Table 5). However, in the literature, it is customary to find that Asians have, in their population, a much higher proportion of distal tumors than non-Asians. In our sample, both ethnicities have a predominance of distal gastric adenocarcinomas, as expected, however, for us, the proportion among non-Asians was 65.85% of distal neoplasms to 15.85% of proximal neoplasms (almost the quadruple). On the other hand, in the group of Asians the proportion went from 60.97% to 12.19% (almost 5 times), respectively. This finding differs from what is found in the literature in general, since the difference in the distal-proximal proportion between both ethnicities was not as large as one could expect [25]. This is probably due to the fact that the Asians we studied, most of them, are Brazilian descendants of Asians. In this way, it is possible that the different dietary patterns and the epigenetic influence of the environment in these patients may influence this finding. Finally, in relation to the stage of the patients, since the survival rates are noticeably more favorable in patients of oriental descent, it is easy to conclude that they must have a less advanced stage. Strong et al. [24], as expected, reports in their results a higher incidence of stage IA in Asian patients. In our study, we could see something similar, Asian patients tend to have a better degree of staging with a tendency for a greater number of patients in stage I compared to western patients, while the latter have higher numbers for stage IV. We then return to the clear fact that the diagnosis in non-Asian patients in our country happens later.

References

- Kim J, Sun CL, Mailey B, Prendergast C, Artinyan A, et al. (2010) Race and ethnicity correlate with survival in patients with gastric adenocarcinoma. Ann Oncol 21(1): 152-160.

- Degiuli M, Sasako M, Calgaro M, Garino M, Rebecchi F, et al. (2004) Morbidity and mortality after D1 and D2 gastrectomy for cancer: interim analysis of the Italian Gastric Cancer Study Group (IGCSG) randomised surgical trial. Eur J Surg Oncol 30(3): 303-308.

- Fielding JW (1989) Gastric cancer: different diseases. Br J Surg 76: 1227.

- Sasako M, Sano T, Yamamoto S, Kurokawa Y, Nashimoto A, et al. (2008) D2 lymphadenectomy alone or with para-aortic nodal dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med 359(5): 453-462.

- Sierra A, Regueira FM, Hernandez Lizoain JL, Pardo F, Martinez Gonzalez MA et al. (2003) Role of the extended lymphadenectomy in gastric cancer surgery: experience in a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol 10(3): 219-226.

- Wu CW, Hsiung CA, Lo SS, Hsieh MC, Shia LT et al. (2004) Randomized clinical trial of morbidity after D1 and D3 surgery for gastric cancer. Br J Surg 91(3): 283-287.

- Kim Y, Park J, Nam BH, Ki M (2015) Stomach cancer incidence rates among Americans, Asian Americans and Native Asians from 1988 to 2011. Epidemiology and health 37: e2015006.

- Kamangar F, Dores GM, Anderson WF (2006) Patterns of cancer incidence, mortality, and prevalence across five continents: defining priorities to reduce cancer disparities in different geographic regions of the world. J Clin Oncol 24(1): 2137-2150.

- Lee J, Demissie K, Lu SE, Rhoads GG (2007) Cancer incidence among Korean-American immigrants in the United States and native Koreans in South Korea. Cancer control : Cancer Control 14(1): 78-85.

- Gill S, Shah A, Le N, Cook EF, Yoshida EM (2003) Asian ethnicity-related differences in gastric cancer presentation and outcome among patients treated at a canadian cancer center. J Clin Oncol 21(11): 2070-2076.

- Washington K (2010) 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Ann Surg Oncol 17(12): 3077-3079.

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer 2011 14(2): 101-112.

- Siewert JR, Stein HJ (1996) Carcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction - classification, pathology and extent of resection. Diseases of the Esophagus 9(3): 173-182.

- Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P (2005) Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin 55(2): 74-108.

- Hamashima C, Systematic Review G and Guideline Development Group for Gastric Cancer Screening G (2018) Update version of the Japanese Guidelines for Gastric Cancer Screening. Jpn J Clin Oncol 48: 673-683.

- Kim H, Hwang Y, Sung H, Jang J, Ahn C, et al. (2018) Effectiveness of Gastric Cancer Screening on Gastric Cancer Incidence and Mortality in a Community-Based Prospective Cohort. Cancer Res Treat 50(2): 582-589.

- Chen Y, Haveman JW, Apostolou C, Chang DK, Merrett ND (2015) Asian gastric cancer patients show superior survival: the experiences of a single Australian center. Gastric Cancer 18(2): 256-261.

- Castro OAP, Tagawa ACS, Perea MRF, Vicenzi R, Saab P, et al. (2005) Nutritional Evaluation of Gastric Cancer Patients. Paper presented at: 6th International Gastric Cancer Congress, Yokohama, Japan.

- Ceylan Isik AF, McBride SM, Ren J (2010) Sex difference in alcoholism: who is at a greater risk for development of alcoholic complication? Life Sci 87(6): 133-138.

- Menezes AM, Lopez MV, Hallal PC, Muino A, Perez Padilla R, et al. (2009) Prevalence of smoking and incidence of initiation in the Latin American adult population: the PLATINO study. BMC Public Health 9: 151.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information (2019) PubChem Database. Benzoapyrene CID=2336.

- Cislo M, Filip AA, Arnold Offerhaus GJ, Cisel B, Rawicz Pruszynski K, et al. (2018) Distinct molecular subtypes of gastric cancer: from Lauren to molecular pathology. Oncotarget 9(27): 19427-19442.

- Stessin AM, Sherr DL (2011) Demographic disparities in patterns of care and survival outcomes for patients with resected gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 20(2): 223-233.

- Strong VE, Song KY, Park CH, Jacks LM, Gonen M, et al. (2010) Comparison of gastric cancer survival following R0 resection in the United States and Korea using an internationally validated nomogram. Ann Surg 251(4): 640-646.

- Yu X, Hu F, Li C, Yao Q, Zhang H et al. (2018) Clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis of proximal and distal gastric cancer. Onco Targets Ther 11: 1037-1044.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...