Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Mini Review(ISSN: 2690-5752)

Whether it is Possible to Recognize Paleolithic Children’s Toys? Volume 7 - Issue 5

Vadim N Stepanchuk*

- Paleolithic archaeologist, PhD, Dr Sci, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Ukraine

Received: March 06, 2023; Published: March 14, 2023

Corresponding author: Vadim N Stepanchuk, Paleolithic archaeologist, PhD, Dr Sci, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Ukraine

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2023.07.000276

Abstract

The material evidence of Paleolithic children’s activities may well be found amongst items that have been discarded or lost in their time and have managed to survive into the present day. But how can they be recognized amongst the thousands of artefacts and other associated objects? Some “unusual items” and “strange stone tools” from Middle Paleolithic sites are regarded as promising candidates for the attribution to products of the creativity of young Neanderthals [1]. The probability increases if unusual items are non-standard according to basic parameters, or too unskillful or made of too low-quality material and suspiciously impractical, and besides have small sizes [2]. The number of sites and identified material remains of their inhabitants’ activity, both adults and children, increases as we approach our time, so the probability of finding substandard items in Upper Paleolithic sites certainly increases. Especially considering the belonging of their inhabitants to modern humans, and hence undisputedly inherent to them fundamental similarity of the basic norms of social behavior. However, “unusual things” are occasionally found among the commonplace material of the Middle Paleolithic and even earlier sites.

Introduction

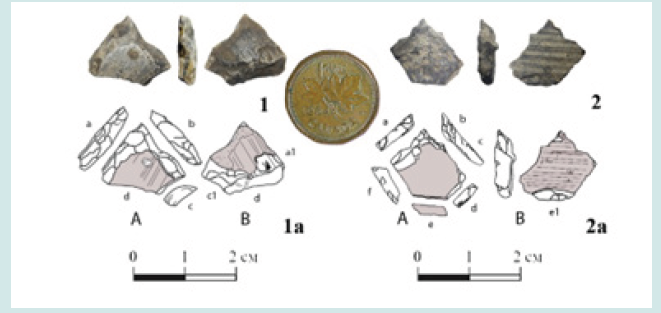

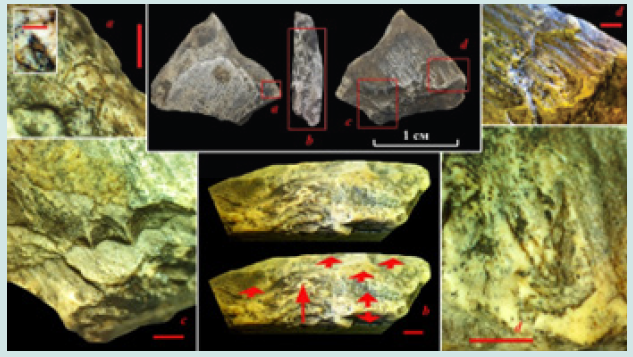

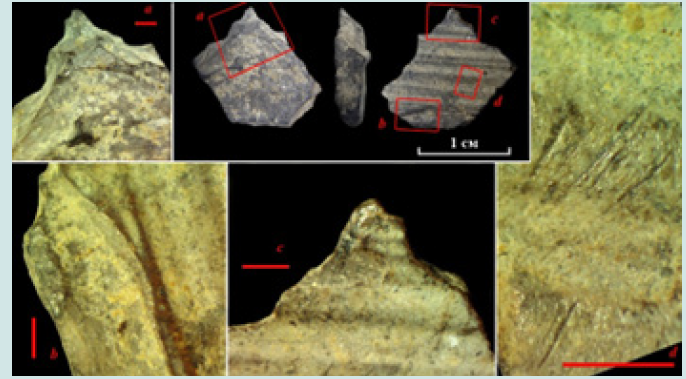

Two items recently identified in the faunal collections of two Pleistocene sites significantly remote from each other in time and space in Eastern Europe are a case in point. Unusual findings per se are the oldest currently known instances of anthropogenic modification of tusk material using bipolar-on-anvil knapping and trimming techniques and retouching [3]. These pieces were recovered at Medzhibozh A, the MIS 11 Lower Palaeolithic openair site in western Ukraine [4], and the MIS 5a Micoquian cave site Zaskalnaya V in Crimea [5]. Medzhibozh find is a miniature, trapezoidal in plan, flat fragment of a tusk dentin growth cone. There are multiple signs of deliberate edging, which has finally given the object a pointed shape (Figures 1&2). The fragment measures 14x16x4 mm and weighs 0.7 g. Zaskalnaya’s find was initially a fragment of the outer cement layer of tusk. Now it is subrhomboidal, with a truncated base, (Figures 1&3) pointed. Virtually all edges, as well as the basal part on the ventral surface, show signs of deliberate working. Dimensions 14x14x3 mm, weight 0.5 g.

Figure 1: Palaeolithic toys? Photographs and drawings of ivory fragments from Medzhibozh A layer I-II (1, 1a), and Zaskalnaya V, layer IV (2, 2a). All edges and partially Surfaces show numerous signs of deliberate processing.

Figure 2: Medzhibozh A, ca.400 ky BP. Details of the anthropogenically modified fragment of the dentin cone of tusk showing various aspects of deliberate splitting. Scale bar 1 mm and inset scale bar 250μm.

Figure 3: Zaskalnaya V, ca.80 ky BP. Details of the anthropogenically modified fragment of the outer cement layer of the tusk displaying scars of intentional retouch, probable use wear and trampling marks. Scale bar 1 mm.

The artefacts are fundamentally similar in terms of the material (tusk, respectively Mammuthus trogontherii and Mammuthus primigenius), the applied processing technique (splitting), size (less than 2 cm), and general morphology (pointed shape). Taking into account the age difference of more than 300 thousand years, the makers of pointed tusk items differed not only in socio-cultural environment and degree of technological advancement but also in terms of anthropological affiliation. For Zaskalnaya V, they are Neanderthals, as confirmed directly by the bone remains found at the site, while for Medzhibozh A, they apparently are some early form of hominin. Nevertheless, in both cases, the solution was very similar: from a miniature fragment of an unusual, and not much suitable for splitting, material to create an impractical, from utilitarian point of view, tiny object using the technology habitually used in the manufacture of stone products. If these similarities are not accidental, we must assume the existence of close reasons for them. An acceptable explanation may be found by assuming that we are dealing with children imitating the process of making stone tools, i.e., imitating the behavior of adults during play. The young inhabitant of the upper layers of Medzhibozh A, who was not at all embarrassed by the small size of the tusk fragment which attracted his attention and by the danger of being injured during vertical splitting on the anvil, imitated in detail the familiar process of making sharp working edges on the fragment of stone. A child from layer IV of Zaskalnaya V, for whom the miniaturization of the workpiece also presented no particular difficulty in handling the piece of tusk found, imitated the standard process of making a pointed piece with a thinned base and perhaps even used it for some time. The utilitarian value of the objects obtained is questionable, indicating that the manufacturing process was not intended to produce a tool but “as if” a tool, an article of pretend manufacture. In other words, we may be dealing with “toys” made by the little inhabitants of Medzhibozh A and Zaskalnaya V, who realised their experiences of imitation and training of adult practices.

References

- Stapert D (2007) Neanderthal children and their flints. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Northwest Europe 1(2): 1-25.

- Shea JJ (2006) Child’s Play: Reflections on the Invisibility of Children in the Paleolithic Record. Evolutionary Anthropology 15(6): 212-216.

- Stepanchuk VN (2023) Unusual Items: Tiny, Pointed, Made of Ivory. Stratum plus (in Russian) 1(2023): 17-32.

- Stepanchuk V (2022) Early human dispersal at the western edge of the Eastern European plain: data from Ukraine. L’Anthropologie 126(1): 102977-102985.

- Kolosov Yu G (1983) Mousterian Sites of the Belogorsk Region. Kiev, Naukova Dumka (in Russian).

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...