Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Research Article(ISSN: 2690-5752)

UN Peacekeeping, Participatory Action Research (PAR), and Tanzanian Artisanal Handicrafts Volume 7 - Issue 2

Edad Mercier1* and Maria Ellis2

- 1History Professor, St. John’s University, USA

- 2Director of WomenCraft Social Enterprise in Ngara, Tanzania

Received: August 05, 2022 Published: September 06, 2022

Corresponding author: Edad Mercier, History Professor, St. John’s University, New York, USA

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2022.07.000257

Abstract

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Participatory Action Research

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- WomenCraft and PAR

- WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Conclusion

- References

The purpose of this article is to explore the relevancy of Participatory Action Research (PAR) in international development. The authors critically assess PAR methodologies in the Tanzanian context through a reflective participant study of the artisanal handicraft association WomenCraft based in Ngara. In addition to exploring the challenges of data collection in fragile and postconflict regions, the authors examine ways to implement and adapt tools and guidance on conducting field research from United Nations member organizations.

Introduction

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Participatory Action Research

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- WomenCraft and PAR

- WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Conclusion

- References

Following the Burundian Civil War between 1993 and 2005, nearly 400,000 Burundian refugees fled to neighboring Tanzania seeking asylum. The United Nations Operation in Burundi (ONUB) and African Union Mission in Burundi (AMIB) were deployed to help with disarmament and enforcement of the Arusha Accords from 2000. Hundreds of refugee camps were set up along the Tanzanian border near Lake Tanganyika. In Kigoma and Kagunga villages, almost 200 refugees arrived from Burundi daily after the Civil War. However, basic needs, like access to water, education, health care, and sanitation, were not met in the village camps. After the signing of the Arusha Accords, resettlement operations were complicated by several factors, including high reproductive mortality rates, malaria, and cholera outbreaks, sexual and gender-based violence, and child malnutrition. Inadequate training of humanitarian aid workers and limited technical expertise on gender-mainstreaming methodologies compounded by a shortage of intergovernmental funding for long-term critical programs for refugee resettlement worsened conditions in the camps.

Between 2009 and 2017, the Tanzanian government announced restrictions on Burundian refugees, including closures of border entry points, and denials of asylum applications. In 2018, the United Nation Children’s Fund (UNICEF) reported that nearly 60 percent of Burundian refugees were still living in refugee camps, Nyarugusu, Mtendeli and Nduta in Tanzania. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Tanzanian, and Burundian government leaders have also overseen the informed and voluntary repatriation of close to 100,000 Burundians since 2020.

Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Participatory Action Research

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- WomenCraft and PAR

- WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Conclusion

- References

Studies by UN Women, the International Labour Organization (ILO), UNHCR, and UN Habitat show that data disaggregated by sex are critical for implementing targeted rehabilitative programs in fragile situations, such as refugee camps. Sex disaggregated data are used to address “gender indicators” related to causes of female and male mortality/morbidity; infant mortality rate by sex and cause; rates of women’s political participation; proportion of women and men employed in different levels/areas of the public and private sector; and differences in wages earned by female/male workers. Gender disparities in access to housing are especially problematic for refugee women. According to UN-HABITAT, “close to one third of the world’s women are homeless or live in inadequate housing [1].” Poor women in urban areas with substandard or no housing are particularly marginalized, because they are easy targets of violence. In urban slums, there is a high prevalence of risky sexual behavior among women and girls in order to meet housing and other basic needs (i.e., trading sex for food or housing). This makes women and girls vulnerable to HIV/AIDS and STIs, psychological trauma and other abuses [2].

Beyond the material value of housing, there is also an “identityforming and fashioning” component of housing that is critical in creating “a psychological state whereby one can construct a self, first for one’s own self, then for others [3].” Without the social, psychological, and emotional stability that safe housing fosters, the ability of individuals and communities to meet basic needs becomes even more difficult. UNESCO outreach events for girls’ education as part of the Kigoma Joint Programme in Tanzania emphasize the importance of parent involvement, traditional and regional leadership in developing regulatory guidelines. The Kigoma Joint Programme has brought together more than sixteen different UN organizations, including Sustainable Energy and Environment (SEE), Youth and Women’s Economic Empowerment (YWEE), and Violence Against Women and Children (VAWC) to achieve goals of gender parity in education and microfinance entrepreneurship [4].

Participatory Action Research

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Participatory Action Research

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- WomenCraft and PAR

- WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Conclusion

- References

Participatory Action Research (PAR) is a collective, public, and scientific action inquiry research methodology that effectively integrates “gender indicators” social and psychological factors into research design and practice. PAR is a reflexive practice that empowers both the researcher and participant to engage in collaborative interventions for improvements to community health and safety. PAR is used to develop solutions to reduce poverty, eliminate discrimination, and promote leadership skills. Participatory action research in developing countries supports grassroots technical training on gender-based planning for women workers as a “self-help” approach.

PAR is sometimes characterized as “living knowledge” that benefits community members, scientists, and non-scientists [5]. Storytelling and oral history research are PAR methods that are used as both a methodology of action inquiry and decisionmaking assessment in vulnerable communities to build reflective knowledge. Critical ethnographers may sometimes employ PAR and oral history research to test anthropological theories on power, cultural change, and institutional relations, as shown in Lila Abu- Lughod’s Writing Women’s Worlds: Bedouin Stories (1993). Abu- Lughod’s work challenged Third World women’s representations in the West and navigated the complexities of emotions and politics involved when trying to evaluate collective and individual memories alongside the process of memory making in families through a feminist lens [6].

The discourse of “Third World Difference” has advanced the “female half” of the nation narrative over the past fifty years. The “Third World Difference” model prevails in international development circles today-justifying programs that promote gender mainstreaming like the 2030 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals-Goal 5 [7]. “Third World Difference” is also a framework for thinking about how women from the Global South are included in discussions on unpaid care work, household care burdens, and “basic needs” without essentializing people’s experiences or identities [8].

Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Participatory Action Research

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- WomenCraft and PAR

- WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Conclusion

- References

When Working with Vulnerable People (WWVP) in conflictaffected regions it is important to have SEL skills as a communitybased participatory action researcher. SEL considers gender, race, class, and cultural differences, while promoting collaborative cluster models of cooperation to promote equitable decision making. SEL skills taught in classroom settings for instance can improve cultural and gender sensitivity practices amongst students, teachers, and administrators.

SEL “involves implementing practices and policies that help children and adults acquire and apply the knowledge, skills, and attitudes that can enhance personal development, establish satisfying interpersonal relationships, and lead to effective and ethical work and productivity. These include the competencies to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show caring and concern for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions [9].” SEL encourages researchers and educators to practice mindfulness by examining biases to improve cultural competencies and emotional intelligence. Integrating self-care for self-awareness might include meditation and low impact exercises to manage trauma and build resilience. Stress management, problem solving, integrity and dependability, and time management are also important SEL skills to integrate into the research design phase.

War and social unrest are particularly destructive for both hard and soft infrastructure systems, such as research, training, and SEL education. Refugees and displaced persons must be accounted for in soft skills training. SEL and PAR training in these emergency situations can serve humanitarian goals, such as promoting reconciliation and stability, and creating safe spaces for displaced persons. Education in Emergencies (EIE) is a subset of international development practice that addresses the challenges of delivering education and SEL services during crises. EIE aims to fill the gaps in education services delivery by promoting safe learning environments and coordinating with humanitarian teams to train teachers, provide learning supports, and collect data on displaced and refugee pupils. Yet, according to UNICEF, less than 3 percent of humanitarian relief aid is directed to the education sector. Through PAR with teacher and student participants, SEL can be integrated into EIE as a humanitarian goal and analyzed for long-term effectiveness in terms of student academic performance, social and emotional stability.

Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Participatory Action Research

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- WomenCraft and PAR

- WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Conclusion

- References

There are ethical obligations that come into play every day with PAR. For example, how does a PAR field scientist practice impartiality while respecting community beliefs? How does a researcher empower victims, refugees, detainees, or other vulnerable individuals to speak up? Also, how do researchers build accountability for their work in the field? Some recommendations are to practice non-discrimination by creating safe spaces for individuals to express concerns. Also, being “ethically effective” in the field means setting personal and professional expectations and outcomes that are clear and transparent between the participant and researcher. During any crisis, whether it be armed conflict or a pandemic, it is critical not to stigmatize or isolate certain groups, which can lead to more shame, fear, unsafe health practices, and limited communication. It is important to adopt a Human Rights- Based Approach (HRBA) to decision making for PAR studies to promote inclusive and ethical research design. In the past, country officials have used HRBA in the Truth and Reconciliation Commissions of South Africa post-apartheid; Iraq’s 2009 Common Country Assessment (CCA) during disarmament; and risk assessment plans in the Caribbean and Latin America following natural disasters.

HRBA calls on local officials to identify and outline the roles and responsibilities of ‘duty bearers’-those who must fulfill obligations; and ‘rights-holders’-those who claim rights to nondiscrimination, affordability, accessibility to information, and physical accessibility. States also have obligations to respect the public, protect the vulnerable, and fulfill agreed upon standards. A HRBA model in PAR means identifying the duty bearers. For instance, if developing a PAR study in a hospital to build local capacity, the duty bearers might be nurses, doctors, human and health services professionals. Outlining how these duty bearers perceive their responsibilities, and the actual requirements of their profession can lead to more ethically effective reporting and feedback.

Integrating HRBA in PAR also signifies adopting clear guidelines at the outset of the study on informed consent, testing, privacy, experimentation, rewards disbursement, and medical declarations for rights-holders. These guidelines should include waivers that attest to policies on recording, interviewing, research documentation, and publication between participant and researcher. Also, for certain study participants, signing waiver forms may not be a common or acceptable practice because of religious or cultural considerations. In these situations, the field researcher(s) should be responsible for obtaining alternative tools for participation and consent. These alternative means might include hiring a local, humanitarian interpreter to assist with verbal agreements. PAR practitioners should also actively integrate the “autonomy and independence” principle into their work by recognizing the rights of individuals to exercise free will based on their own set of values. The “autonomy and independence” principle is sometimes used interchangeably with neutrality and impartiality to describe “principled humanitarianism.” Principled humanitarianism is described as a “commitment to meet the assistance and protection needs of affected populations in a way that is distinct and separate from political and other motivations [10].”

The UNHCR Emergency Handbook further explains that “The neutrality of humanitarian action is further upheld when humanitarian actors refrain from taking sides in hostilities or engaging in political, racial, religious or ideological controversies. At the same time, independence requires humanitarian actors to be autonomous. They are not to be subject to control or subordination by political, economic, military or other nonhumanitarian objectives [11].” Although PAR scientists are not necessarily humanitarian actors, their work frequently coincides with humanitarian objectives, such as promoting peace, equity, and security for all. Being mindful of these objectives while conducting PAR will help promote accountability and transparency in program deliverables, while supporting the sustainability of study findings.

Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Participatory Action Research

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- WomenCraft and PAR

- WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Conclusion

- References

Data collection with limited resources and low-literacy populations can be difficult in the field and lead to research bias. There are several types of biases that can be produced either during research design or data collection. Selection bias occurs where the researcher’s collection samples are neither representative of the population nor randomized. The pitfalls of selection bias are that the research findings will end up skewed and lead to misclassifications. Misclassification bias is when participants in a study or experiment are incorrectly assigned to a group, which may lead to false associations. Volunteer bias “refers to a specific bias that can occur when the subjects who volunteer to participate in a research project are different in some ways from the general population. If this occurs, the researcher has sampled only a subset of the population, and consequently, the data gathered are not representative of all people, merely of those that choose to volunteer [12].”

Self-reporting bias is found in situations, where social pressures may lead to misrepresentation or misreporting of data. Althubaiti writes “When researchers use a survey, questionnaire, or interview to collect data, in practice, the questions asked may concern private or sensitive topics, such as self-report of dietary intake, drug use, income, and violence. Thus, self-reporting data can be affected by an external bias caused by social desirability or approval, especially in cases where anonymity and confidentiality cannot be guaranteed at the time of data collection [13].” Self-reporting bias can also lead to assumptions about the participants and further stigmatize vulnerable, affected groups.

Bias in data interpretation may also lead to overdrawn conclusions based on broad or misleading assumptions. Simundić highlights several examples of bias in data interpretation, such as “discussing observed differences and associations even if they are not statistically significant (the often used expression is ‘borderline significance); discussing differences which are statistically significant but are not clinically meaningful; drawing conclusions about the causality, even if the study was not designed as an experiment; drawing conclusions about the values outside the range of observed data (extrapolation); overgeneralization of the study conclusions to the entire general population, even if a study was confined to the population subset [14].” PAR scientists have an obligation to produce transparent observational data that can improve reporting and feedback cycles. This might involve rapid humanitarian needs assessments, collecting and interpreting perception data on attitudes, beliefs, and awareness, and checking for biases throughout data collection.

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) launched the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Multi-Cluster/Sector Initial Rapid Assessment (MIRA) tool to aid field-based relief workers and community stakeholders with conducting reliable and rapid humanitarian needs assessments in emergency situations pre-crisis and during crisis. The MIRA framework incorporates certain PAR methodologies, such as joint assessments, direct observation (DO), key informant interviews (KII), community group discussions (CGD), and semi-structured questionnaires. MIRA is an important instrument for conducting primary and secondary data collection, while checking for biases. Under MIRA, researchers are encouraged to do the following:

a) Always review tools and plans already in place or used in the past and consider how to make best of use of them.

b) One size does not fit all. Take time to adapt data collection tools based on the results of the secondary data, the adapted framework and the context. Translate carefully, field-test tools, and refine accordingly.

c) Limit the number of questions to be asked at the field level and do not collect information that is available from other sources, or that cannot be collated and analysed within the desired timeframe. Do not seek more detail than necessary.

d) Ensure that priorities expressed by the population and identified by the assessment teams are captured systematically and consistently, both views count [15,16] (Figure 1).

The MIRA guide recommends Purposive Sampling- “In purposive sampling, there is one or more specific, predefined group or location selected for data collection. Purposive sampling can be very useful in situations where a targeted sample needs to be reached quickly and where sampling for proportionality is of lesser importance. It involves defining which characteristics or criteria are important according to the assessment objectives (e.g., affected population in urban vs. rural areas), and visiting sites or localities that represent a cross- section of these [17].” Purposive sampling also helps add a gender lens to data collection strategies, by requiring assessment teams to think about how gender inequalities worsen humanitarian crises. Factors such as male to female ratios and data disaggregated by sex, age, and income are analyzed through purposive sampling. Language also matters in data collection. Culturally responsive language for social interaction is critical to minimize confusion, alongside effective body language for communication and interpretation, and instructional support for non-native language speakers and learners. The MIRA guide advises translating all key findings into the local languages of the affected population(s) [18]. PAR design should also include local language terminology for valid interpretation of data analysis (Figure 2).

PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Participatory Action Research

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- WomenCraft and PAR

- WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Conclusion

- References

As an evidence-based methodology, PAR encourages inclusive humanitarian action. In 2007, using community-based social survey instruments, the Centre of Studies for Peace and Development (CEPAD) in Timor-Leste used PAR to develop an anticorruption manual and “Peace Houses”-spaces where community leaders meet to discuss public priorities, resolve conflicts, and raise awareness on issues of concern. CEPAD and Peace Houses have been central in the development of the Frameworks for Assessing Resilience (FAR) in Timor Leste, which develops recommendations for building resiliency in fragile communities. PAR is also used in developing contexts to reduce health care disparities by empowering disenfranchised groups to take ownership of their health and enabling health managers to provide consistent and prompt feedback. Tetui et al. found that Makerere University College of Health Sciences – School of Public Health (MakCHS-SPH) integrated PAR to develop Maternal and Neonatal Implementation for Equitable Systems (MANIFEST), empowering both patients and physicians to provide input on their experiences with the local health care system.

Between 2014 and 2015, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) partnered with the Ministry of Health in Somalia in a participatory mapping project to identify community health partners and public health indicators in three zones. The goal was to improve standard access to health care and identify critical areas for intervention, like the creation of mobile clinics, with community input from women’s and indigenous groups. A study by researchers in Johannesburg released in 2020 found that PAR could be used to promote collaborative learning and reduce discrimination in fullservice schools. The research team implemented PAR methods such as research journals, focus groups, and interviews to promote inclusive teaching practices. Findings from the study were that PAR empowered teacher participants to engage in more reflective classroom practices, which included identifying students with learning disabilities early on and developing a “referral system” with a learner support educator (LSE).

WomenCraft and PAR

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Participatory Action Research

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- WomenCraft and PAR

- WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Conclusion

- References

WomenCraft is in Ngara, a town in the Kagera Region of Tanzania, bordered by neighboring countries Rwanda and Burundi. From its beginnings in 2007, WomenCraft Social Enterprise has adopted a cross-border “peace-centered approach” that employs PAR methodologies, such as social surveys, to support women refugees in Rwanda, Tanzania, and Burundi. WomenCraft’s daily operations are conducted in English, Kiswahili, Kinyarwanda, and Kirundi. Staff are a combination of expatriates, international visitors, and local consultants fluent in English, Kiswahili, and other languages. Partnering with the UNHCR, National Microfinance Bank of Tanzania, local and international faith, and community-based organizations, WomenCraft currently collaborates with female refugees and survivors of gender-based violence from the Burundi Civil War to support technical and artisanal skills development, and improve long-term outcomes in the domains of education, employment, and preventative health care.

The production process for WomenCraft basket weaving includes peer and kin learning networks among the women. WomenCraft basket weaving production consists of providing the artisan groups a sample of the item to be created, along with measurement templates, rulers, and any other necessary tools required to ensure that the hand-woven baskets are as uniform as possible. Senior artisans will sometimes recruit other women in the community to join in the basket weaving. After several weaving “trials,” where techniques such as coiling, stitching, and designs patterns are taught, artisans start to produce handicrafts for sale. Basket weaving was a fading tradition in the region of Tanzania where WomenCraft is located. Although the basket weaving tradition continued in Burundi and Rwanda, the demands of family life, as well as the destruction of natural habitats because of regional conflicts, reduced the time and opportunity for plant tending, gathering, and weaving. The policies of the Tanzanian government, which led to refugee camp closures and forced returns, meant that the most skilled weavers were no longer present to teach the next generation. In addition, the adoption of plastic and metal objects, lessened the local demand for handwoven baskets.

The elders in the community were tapped to provide guidance and instruction to teach the younger generation to help revive and sustain their cultural practices. From there, an each one, teach one model has been beneficial to the production process. Every WomenCraft group has a leadership team, and these women are instrumental to mentoring and teaching the next generation of basket weavers. The leadership team may delegate responsibilities, including fabric selection, banana leaf stripping, and materials distribution. Sustainable, aesthetic, heritage, and environmental development goals are also integrated into production. WomenCraft addressed the sustainability challenges of production for an international market by securing its membership status in the World Fair Trade Organization. This enables the social enterprise to export products created with raw materials, such as natural grasses and banana leaf, without facing import restrictions.

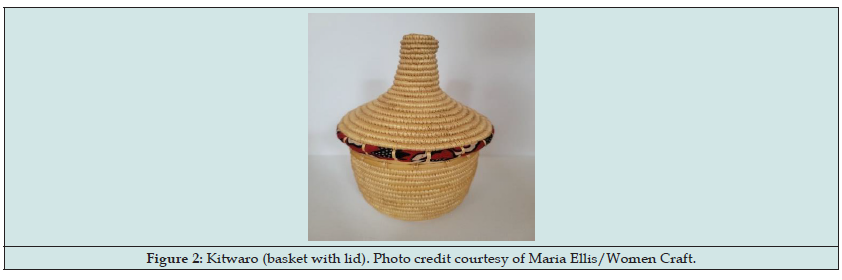

WomenCraft has firmly established its presence and unique designs within the Tanzanian and regional East African tourist markets. A special combination of impeccable weaving skills and locally sourced raw materials, paired with high visibility and product marketing has ensured that attempts to imitate its designs will be difficult. The WomenCraft basket designs, such as the kitwaro (basket with lid) and handled baskets, are traditional designs that have been created by the local women for ages. Locally grown, hand harvested grasses and banana leaves are sourced and used to weave the baskets. In addition, fabric that is traditionally worn by the women is incorporated into the designs. One of WomenCraft’s goals with its product designs is to incorporate a traditional aesthetic while appealing to a global market. This ensures that product sales will remain steady not only in the Tanzanian tourist market, but the international market as well.

The problem that WomenCraft staff endeavored to address in the decade following the Burundi Civil War was how to assess the failures of peacekeeping missions that had already ended in refugee camps, while identifying the critical gaps in social services delivery, impacting women and children. PAR semi-structured social surveys and open-ended questionnaires of Burundian female refugees conducted by WomenCraft staff, including the authors, between 2007 and 2009, covered 10 areas of interest that were the following-family, health, violence/substances, housing, water, education, religion, social/community, and other. The Burundian artisans interviewed were from the Upendo group in Mubayange village, Twitezimbele group in Mubayange village, and Baraka group in Gichacha village. The artisans were encouraged to speak in their native languages with the aid of a humanitarian interpreter. PAR methods employed during surveying included confidential, individual discussions, group work, and rural action research to gather opinions on education, religion, and income support strategies. Arts-based critical reflection methods were also integrated as part of an iterative research cycle to outline goals for our participants that included opening independent clothing shops and sending their children to school.

WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Participatory Action Research

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- WomenCraft and PAR

- WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Conclusion

- References

Visitors to Ngara may still see small to medium-sized white makeshift offices that read “United Nations” in blue. But little else remains of the UN peacekeeping ground missions in the region that lasted for several years following the genocide in Rwanda and Burundi Civil War. The few international NGOs remaining handed over tasks to local staff following the end of peacekeeping missions. Efforts to reduce poverty also redoubled, with investments in initiatives like microfinance and agribusiness. PAR in this context has been critical in leveraging prior knowledge and experience from foreign aid workers, while investing in local capacity building projects responsive to present needs within refugee camps. PAR ultimately enabled WomenCraft staff to identify areas of improvement within the organization. For example, team meetings were held more frequently, and task rotation on a weekly basis was implemented to give opportunities to younger artisans to build new competencies in software, sales, marketing, design, and leadership. Additionally, feedback from action research encouraged more brainstorming sessions with group leaders to develop feasible and creative ideas for packaging, logos, and marketing.

WomenCraft’s artisan financial literacy program was designed from PAR survey findings that highlighted participants’ interest in starting savings accounts to invest earnings from handicraft sales. Other findings from the PAR survey findings were that WomenCraft artisans were especially interested in using their earnings to send their children to school. Certain artisans had attended primary school but were unable to start secondary school for financial and cultural reasons. Some of the women shared memories of their time in school as being the happiest moments in their childhood and expressed wanting their children to have a postsecondary education. Other results from PAR and field-based observations revealed that more strategies for reinforcing social and cultural rights in vulnerable refugee communities are needed in the Tanzanian context. Refugees should be allowed to freely maintain their social and cultural practices in refugee camps without facing any restrictions or negative repercussions. It would be beneficial to ensure that refugees also have enough arable land to farm to help sustain their families without being fully dependent upon camp rations or handicraft earnings. Since funding has been cut by international agencies and there is a shortage of basic supplies such as soap, cooking utensils, mats, and blankets, refugees should be permitted to create their own supplies if the resources and raw materials are provided.

Authorities should also provide protection and relief to vulnerable refugee communities rather than treating them unfairly and as a burden. Legal, social, economic, and political barriers should be eliminated so that refugee men and women can contribute to the safety of camps. Encampment policies and limited access to livelihood opportunities must be addressed to ensure that evacuees and repatriated individuals can live in a more dignified manner. The closure of international markets and economic activities has had a detrimental effect on the income generating opportunities of refugees and the host community. These policies must be reversed to reinforce the rights of refugees to a earn a living wage.

Conclusion

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Participatory Action Research

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- WomenCraft and PAR

- WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Conclusion

- References

The PAR approach combines qualitative and quantitative methodologies to build transparency and promote sustainability. Using PAR during periods of leadership transition and administrative overhauls also strengthens feedback and reporting mechanisms so that evidence-based interventions are implemented. Social workers, educators, and public health officials sometimes cite action research as the vehicle for social justice. Yet, PAR does not necessarily have to be anchored by a social justice mission. PAR, at its foundations, concerns identifying the root causes of systemic inequalities and orienting resources to support robust problem solving amongst community stakeholders. As a reflective research methodology, PAR also encourages study participants to consider how their own SEL and technical skills are leverageable in the given context. The idea of self-help and self-awareness through PAR is significant for developing community, family, and individual resiliency. Especially during periods of crisis, collective input and reporting from marginalized groups helps build a sense of confidence and trust in the rebuilding or resettlement process.

References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Using Data to Measure Inequalities

- Participatory Action Research

- Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Skills for PAR

- Ethical Obligations to Promote Social Inclusion

- Methodologies for Mapping and Data Collection

- PAR Evidence-Based Case Studies

- WomenCraft and PAR

- WomenCraft PAR Findings

- Conclusion

- References

- Abu Lughod Lila (1993) Writing Women’s Worlds: Bedouin Stories. University of California Press, USA.

- (2021) Achieve Gender Equality and Empower All Women and Girls. UN SDG Goal 5/UNDESA.

- (2021) Adolescent Girls in Disaster and Conflict. UNFPA (2016).

- Althubaiti A (2016) Information Bias in Health Research: Definition, Pitfalls, and Adjustment Methods. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 9(1): 211-217.

- Ayaya Gladys, Tsediso Michael Makoelle, Martyn van der Merwe (2020) Participatory Action Research: A Tool for Enhancing Inclusive Teaching Practices Among Teachers in South African Full-Service Schools. SAGE Open 10(4): 1-8.

- Chevalier JM, Buckles DJ (2019) Participatory Action Research: Theory and Methods for Engaged Inquiry (2nd), Routledge pp. 1-434.

- Domitrovich Celene E, James P Comer, Joseph A Durlak, Roger P Weissberg, Thomas P Gullotta (2015) (eds.). Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice. Guilford Publications, New York, United States.

- (2009) Gender Equality for Smarter Cities: Challenges and Progress. UN-HABITAT, Kenya p. 1-42.

- (2021) Humanitarian Principles. UNHCR Emergency Handbook, Switzerland.

- (2021) Kigoma Joint Programme, Special Edition, March 2019. United Nations Tanzania, Tanzania

- (2015) MIRA Guidance. IASC/UNOCHA.

- Mohanty Chandra, Russo A, Torres L (1991) Third World Women and the Politics of Feminism. Indiana University Press pp.1-352.

- Rose Carol (2013) The Psychologies of Property. In The Philosophical Foundations of Property Law, edited by JE Penner, HE Smith. Oxford University Press, UK.

- Salkind NJ (2010) Encyclopedia of research design (Vols. 1-0). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc. USA.

- Simundić Ana Maria (2013) Bias in Research. Biochemia medica 23(1): 12-15.

- Tetui M, Coe AB, Hurtig AK, Ekirapa Kiracho E, Kiwanuka SN (2017) Experiences of Using a Participatory Action Research Approach to Strengthen District Local Capacity in Eastern Uganda. Global health action 10(sup4): 1346038-1346045.

- (2015) Understanding Resilience from a Local Perspective: Frameworks for Assessing Resilience Timor-Leste Country Note. Centre of Studies for Peace and Development (CEPAD) & Interpeace pp. 1-79.

- (2021) Why Focus on Women? UN-HABITAT Publisher, Kenya.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...