Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Review ArticleOpen Access

The Hierarchyand Central Place Patterns of the Chalcolithic Sites in the Bakhtiari Highlands, Iran Volume 2 - Issue 2

Mohsen Heydari Dastenaei*

- Departments of Archaeology, University of Shahid Chamran, Iran

Received: March 16, 2020 Published: May 28, 2020

Corresponding author: Mohsen Heydari Dastenaei, PhD in Archaeology, Assistant Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Shahid Chamran, Ahvaz, Iran

Abstract

In archeology, there is a close connection between the size of the ancient places and the level of their social and economic complexity, without understanding and studying it, archaeologists cannot understand the cultural structure of the region. In this hypothesis, the larger of the settlement, the more administrative and social services are provided, and thus has a more complex administrative and economic structure than smaller ones.Accordingly, with the aim of determining the central place and hierarchy,the middle and late Chalcolithic sites ofthe Laran districtin the Zayandeh-Roud basin were studied.To determine the central place and hierarchy of settlement in a mountainous area, using GIS and SPSS software and using cluster analysis method, middle and late Chalcolithic sites were classified and studied and it was determined thatsocieties of Chalcolithic period in the mountain valleys of the Laran district, along with other Zagros valleys, have taken to complex societies, so that there is a two-rank pattern in the middle Chalcolithic period and there is a three-rank pattern in the late Chalcolithic period.

Keywords: Zayandeh-Roud Basin; Hierarchy; Central Place; Settlement Patterns; Chalcolithic Sites; Iran

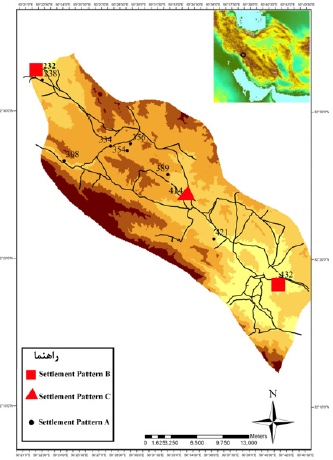

Geography and Ecosystem of Laran

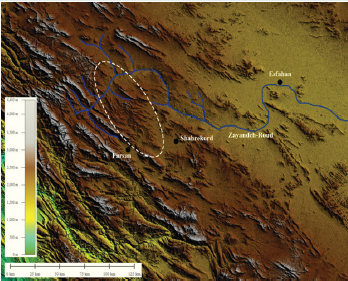

Laran district with a total area of 516.28 km2 is adjacent from north with Isfahan province, from northwest and west with Kuhrang city, from east and south with Shahrekord city and southwest with Farsan city (Figure 1).The region is originally a valley with a northwest-southeast direction along with smaller sub-valleys, which have environmentally, permanent water resources including the Zayandeh-Roudbasinin the north and the southern parts of the Karunbasin and permanent and seasonalsprings, and now it is a countryside and one of the routes and roads of the migration of tribes of Bakhtiari. The altitude of the area is more than 2036 m and the subsistence of the today’s people of the region is low due to the lack of level and flat lands, herding, nomadism, permanent agriculture and aquaculture. According to the data and statistics, the average rainfall in the stations of the region for the past 19 years in March was 72.2 mm and the average of the lowest rainfall in 19 years was in August with an average of 0.7 mm. The coldest month is also in Novemberand December with an average temperature of -24 °C and the highest recorded temperature in July and August with an average of 46 °C [1-8].

Theoretical foundations of Central Place and Hierarchy

One of the most scientific models of construction of settlements that affects socio-economic development programs in different countries and regions is the central place theory of Walter Christaller (1969-1873) 1which was published in 1933 in his book Central Places in the South of Germany.This theory is closely related to hierarchy and originates from the human and economic geography2. Christaller, inspired by von Thünen’s scientific theories (agricultural landuse), Alfred Weber (the location of industries), and Wangglender (transport fare) developed the theory of central place. This theory was not considered until the 1950s until it was translated into English and published in 1966, and since then it has become the basis of urban-regional studies and has gained world renowned. In 1940, he produced the Economic Spatial Organization, along with August Lösch. The basis of Christaller theory is based on the order in the number, size, distance and spatial arrangement of the central places according to their functions and hierarchies in their habitat3. This theory was based on a model in which settlements were classified according to the amount of communication, service, delivery and accessibility, and each one was placed in a particular rank. The main purpose of the central place theory is to explain the spatial organization of the settlements and their sphere of influence4. About two years later, in the toughest conditions of the Second World War, “AugustLosch”, changed a part of the hypotheses of Christaller model and established an urban system that was more consistent with the truth5. Contrary to the Christaller model in the Losch model, cities of the same size can produce and supply various goods and services. The urban hierarchy system is the result of the theory of central places can be demonstrated in its simplest form by using mathematical tools, and there is usually a direct relationship between the number and diversity of activities and the city’s population. Therefore, it can be said that cities that are located on higher levels have more population. In this case, the city on the first level is the smallest city in the urban hierarchy, and the city on the top level has the largest city in that urban system. From the other features of urban hierarchy based on the theory of central places, the distance between the cities in each level with the class in which those cities are located has an opposite relation. So that the distance between the cities on lower level is less than the distance between the two cities that are on the upper level [8-10].

The central places in one geographical area in each region are one of the larger population centers than the other centers, and the amount of goods and services provided in this larger center is more than the centers around it6 and the direct relationship between work, the size of the population centers with Volume of goods and services provided. In other words, the centers that do production activities in order to produce, supply and service are there. Now these centers can either be subordinate and main centers within a city or the city itself is considered as a production center in an urban distribution system. The central place model only has the ability to explain the trading relations of the settlement. It is important when these centers may be in a region, but not necessarily all or some of them are centralized in a settlement, but also have different settlements of different centers and different rankings in the hierarchy7. In this model, the first class settlements and the settlements located at the nearest distance to the center have the most common cultural interactions with the center, and as the distance from the center increases, settlements become smaller and less important where the proportion of local production increase to the productions affected by the center8. Walter Christaller, bases his theory on a set of assumptions, summarized in the following: the existence of a flat plain, in which, equally, transportation is possible in all directions. There is only one vehicle in the plain. The population has spread evenly throughout the plain. In central places in the plain, for spheres of influence, goods and services are prepared and administrative functions are created. Consumers go to the nearest central place that supplies the goods and services they need. Here, consumers traversed minimum distance to receive goods and services. The suppliers of goods and services economic people and they always try to achieve maximum profits in the plain, and as people considering economic advantage come to the nearest center, the suppliers of goods and services get away from each other to attract more consumers9. In this plain, in some central places, more functions are offered. These central places are at the higher levels of the central hierarchy system, while places that only have multiple functions, work at lower levels of the hierarchy system. At higher levels of the Central places and Hierarchy system, all functions, including functions of lower levels of the system, are also offered. All consumers are in the same position in terms of income and demand for goods and services. In this model, different centers of the settlement system are only known and explained by the type and number of goods, the market for the sale of goods, services, employment and population [11-14].

This theory is presented in the form of spatial view and space, local and temporal volumes of all activities that human beings do to dominate nature and survive. In summary, for the use of the central place model in archeology and for the ancient settlements, the following discursive-hypothetical steps are considered and taken into account in accordance with the available information from archaeological surveys and population estimates:

I. The hierarchy is based on the functional size of the settlements.

II. There is a direct relationship between the functional size and the number of types of goods and services produced in a settlement.

III. The functional size has a close and positive relationship with the population.

IV. The area of a settlement is according to its population. As a result, based on the area of settlements, the population of the sites is estimated and the functional size of the settlement determined based on the population size and then the hierarchy of settlements in the central place model determined by comparing the functional sizes10. Another thing that,in addition to the above, can turn a site to a central place, the geographic factors of the location of the site, such as close distance to mineral resources, rich soils, permanent water resources, can also be a factor in turning a site into a central place11. In archeology, there is a close relationship between the size of the ancient places and the degree of their social and economic complexity (not necessarily), without understanding and studying it, archaeologists cannot understand the cultural structure of the region. In this hypothesis, the location of larger settlement, it provides more administrative and social services and therefore it has more complex administrative and economic structure than the smaller onesand usually the role factor and function of the sites and the extent of the ancient sites are determining factor of the settlement ranking position13, because in sites with more area, more goods and services are provided than areas with less space14, But this is true only about the farmers and urban communities15, and the herdsman -Mobile Pastoralism communities had not the advanced government institutions and their social and economic hierarchy manifests in dignified things, which first appeared in the fifth millennium BC cemeteries of Hakalan and Parchineh have been documented16. According to ethnoarcheological studies, it has been specified that hierarchy and centers have different types of cultural, demographic, socioeconomic, administrative-governmental, and trial17 [15-17].

Cluster Analysis of The Central Plase and Hierarchy of The Middle Chalcolithic Settlement

In the Laran County, 16 sites of the middle Chalcolithic were identified, except for the three sites of Kouganak, Khan Yordi and Derazdarreh 1, which were also inhabited from the early Chalcolithic period, the remaining sites including the Ahmadabad 3 site, Ghokhmish Cheshmeh,Darrehbalamey 1 mound, Tang-e Gazi 3 site, Cheshme Qanbar 2 site, Karimabad site, GozalDarreh 1, Ourang 4mound, JubAsiab 5, Jub Nowrouz Ali 8 site, Qandil Darreh 1, Bidekan 2 and Gold arreh site settled for first time.

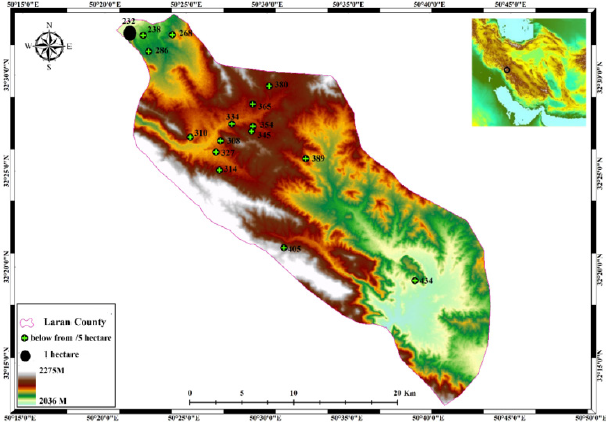

In this analysis, the area of the sites was considered as dependent variable and environmental factors such as distance from water resources, vegetation type and other cases as independent variables. In the analysis of the central place of the seven variables, the relationship between the area of the sites with the Above sea level, the distance between the sites from the communication paths, the distance between the sites from the permanent sources of water, the location of the sitesrelative to the direction and the slope, the location of the site relative to thevegetationand the cluster analysis method was used withWardmethodand Euclidean distance.The result of the cluster analysis of the middle Chalcolithic sites of the Laran district is presented in the form of a diagram (Figure 2). On the chart, each of the colors represents a pattern of settlement, which arein a cluster based on the similarity of the extent of the sites and the environmental features of the middle Chalcolithic sites. Based on these analyzes, two clusters have been obtained.

Figure 2: Diagram of the central place and hierarchy of settlements of the middle Chalcolithic sites.

Settlement pattern A

All sites of the middle Chalcolithic of the LaranCounty are outside the Kuganak mound with code 232, which are located in this settlement pattern and cluster (Figure 3). Altitude from the sea of this settlement pattern is between 2123 to 2547 meters and the distance from the communication routes between nine and 1460 meters. These sites are between 51 and 1757metersfrom permanent resources of water and at a slope of 4.5 to 19 percent. These sites have an area between 1050 and 3000 meters and in terms of slope direction, including slopes with grades 1 to 8, and in terms of land use, most of them in moderate pasture lands, are located in commondry farming lands, pasture and agricultural land. It seems that the hierarchical pattern of this cluster is linear [18- 21].

Settlement pattern B

This settlement pattern consists of a site known as the Kouganak with code 232 (Figure 3), located at an altitude of 2140 meters above sea level. The site is located 18 meters from the communication path and 143 meters from the permanent water resources. The extent of this site is 9100 m and its slope is 5° with the direction of the southeastern slope. This site is in terms of land use in common lands of irrigated agriculture and has the most extent among the sites of Laran district and because of the locating in a strategic and importantposition is in a separate cluster.

Regarding the central place and hierarchy of the Laran district, it should be mentioned that the theory of the central place of Christaller does not apply in this field, because, according to this theory, in each geographic area of a region, one of the population centers is larger than the other centers, and the number of goods and the services offered in this center are more than the other peripheral ones. Although this pattern can be observed in areas without natural obstacles and enclosing factors such as mountains, valleys, large rivers and deserts that prevent the dispersion of places, the size of a site cannot singly beconsidered an absolute indicator for determining a place as a central place, but it can be considered as an important factor in determining a central place. Although the Kouganak mound is located next to the communication path with an area of less than 1 hectare, it should be mentioned that the site is located along natural barriers, including the Zayandeh-Roud River and the mountaintops of the Darre Sib and the DarreBarik of the Isfahan province. On the other hand, the distance between each of the middle Chalcolithic sites with the Kouganak site in cluster B does not follow logical order and does not indicate a center and the peripheral settlements around it. On the other hand, as the peripheral site of first class and second and the other peripheral sites (ranking pattern) diverge from the central place, the extent should be reduced based on their ranking, their population, the distribution of services and vice versa18. This relationship is also not seen among the Laran Chalcolithic sites [22-26].

To analyze this model, the central place and hierarchy of tworank, we should search for other models or cultural, political and social factors in the region. It is worth mentioning that Alizadeh obtained a similar two-rankmodel in research activities in a number of valleys and mountainous plains of north and northeast of Susa in the 5th millennium BC. Many of the sites identified in these regions, which today are also part of the territory of the Bakhtiari tribes, are considered to be camp sites or Pastoral villages with short-term settlements. In some of these plains and valleys there are also central places larger than other sites, and in some periods there was only one single large site. This two-rank pattern with a larger population center is similar to the Qashqaei and Bakhtiari camp sites or castle of khan(tribal chief), which had administrative and settlement centralization in the 18th and 20th centuries19, and Zagarellhas gained this two-rank pattern in his surveys of Shahrekord, Rig Plain and Felard Plains in the Bakhtiari region in the 5th millennium BC20. Theresidence of the Khan or the tribal chief of any tribe in the countryside, in the castle, or in the best and the largestcampsite is close to the main road and the rest of the tribes are spread in the region and inown campsites(Vargah). It seems that this two-rank pattern of Kouganak in a cluster and the rest of the sites are located in a different cluster is similar to the settlement pattern of Bakhtiari nomads, and the Kouganak site can be considered to be somewhat similar to the location of Khan or the tribal chief. So you can call Kouganak a central place because the central person who is the Khan or the tribal chief is in a central place, even though this place is temporary21. However, what matters is the difference between the tribal chiefand other people, on the size of the pastures, the number of herds and the number of people of tribe22, which are not only a sign of power, but also a sign of wealth. The members of this group have a special economic, political and social position, as economically most agricultural lands, desirable pastures and springs23. These people usually live in homes or tents relatively bigger than other members [27-30].

The Cluster Analysis of The Central Plase and Hierarchy of The Late Chaalcolithic Sites

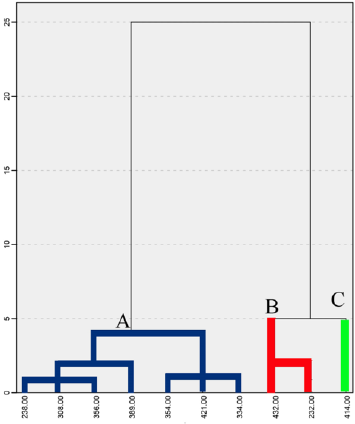

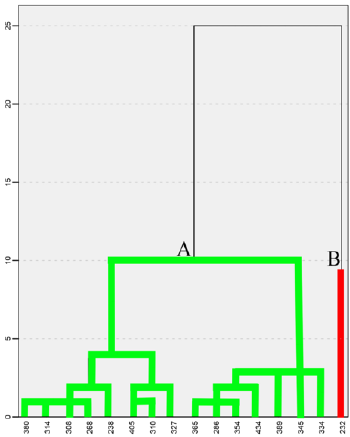

In the Laran district, 10 sites were identified from the late Chalcolithic period, four sites have been formed for the first time, and six sites continued from the middle Chalcolithic period. The result of the cluster analysis of the late Chalcolithic sites of the LaranCounty is presented as adiagram (Figure 4). In the cluster analysis of late Chalcolithic sites, seven variableswas used, the relationship of thesites area to altitude above sea level, distance between sites from communication paths, distance between sites from permanent sources of water, location of sites to direction and slope, The location of the sites to the vegetation and in the analyzes, cluster analysis method and the nearest neighbor method and Euclidean distance were used.In this analysis, the extent of the sites was considered as dependent variable and environmental factors as independent variable. On the diagram, each of the colors represents a pattern of settlement, which is in a cluster,based on the similarity of the environmental characteristics of the late Chalcolithic sites of Laran district. Based on these analyzes, three clusters have been obtained, each one is separately discussed below [31-33].

Settlement pattern A

This cluster consists of seven sites including Ahmadabad 3 (code 238), Tang-e Gazi 3 (code 308), Khanyordi 3 (code 356), QandilDarre 1 (code 389), Khanyordi 1 (code 354), JubNasab 1 (code 421) and Gozal Darre 1(code 334) (Figure5), which has the largest number than other clusters. The height from the sea level of this settlement pattern is between 2206 and 2523 meters and is between 51 and 1757 from the permanent sources of water.The distance of these sites is 9 to 676 meters from communication paths, with a slope between 4.5 and 11 degrees. These settlements have an area of 900 to 2400 meters, and in terms of the slope direction, including the slopes of the group three or eastern: two cases, group four means southeast: three cases, group seven or western: one case, and group eight or northwest also one case and in terms of vegetation, most of them are located in pasture lands and agricultural lands. The location of these sites in the internal system of the habitat and at a distance of 2000 meters from each other, four sites, at a distance of 3000 meters one site and more than 3000 meters two sites are located which have almost a regional focus. What more indicates the regional focus of these sites is locating in a variety of slopes and pasture vegetation that is common to all sites of this cluster. The small extent of the sites compared to other groups, high slope and the high altitude of the sea level compared with the other two groups, more distance from water resources than the other two groups and pasture vegetation seems that these sites are temporary settlements where the subsistence of their inhabitants isnomadic livestock. Zagarell calls these types of sites,”slope sites”.These sites are less than 0/4 hectares and are located in hills, slopes, and nonagricultural regions of poor soil. Zagarellattributes these types of settlements to moving nomads [34-37].

Figure 5: Pattern of the Central place and Hierarchy of the late Chalcolithic sites of Laran County.

Settlement pattern B

The settlement pattern B consists of two sites of the Kouganak mound (code 232) and Kholak(code 432)(Figure 5). Altitude from the sea level of this settlement pattern is between 2140 and 2232 meters and the distance from the communication paths is between 18 and 80 meters. These sites are located in a distance of 143 to 695 meters from permanent water resources and a slope of 5 to 8 percent. The area of this group of sites is between 8400 and 9100 meters, and the height of the cultural layers is to 14 meters. In terms of slope direction including slopes 2 and 4 means northeast and southeast, and in terms of vegetation, they are also located on lands with ability of irrigation agriculture. In terms of locating and distance of the sites in this pattern, it can be noted that these two sites are 41 km apart, so that Kouganak is located in the north and Kholak in the southernmost part of the region. As stated, these sites are located in the final parts of the region, in the vicinity of them are the main roads of the Kouhsefid and Täräz, and one of these sites, the beveled-rim pottery of the Kouganak mound has been obtained. The beveled-rim pottery and Uruk pottery from this site show that these types of sites have not been merely biological function and probably related to controlling the communication paths24. Usually, the distribution of Uruk materials is seen in sites that are capable of controlling high routes and in Zagros these routes are mostly East-West, and most of these routes are located along the river or in pathways and passages between mountains25. The other thing is that these sites are located on the sedimentary terraces of Zayandeh-Roud and Gorgak. Usually, the beds and edges of the rivers are considered to be the best location for agriculture because of the alluvial soils. In other words, the locating of fields along the permanent rivers with rich agricultural soils, lower altitude, proximity and easy access to communication routes, slopes less than ten degrees and rich surrounding pastures have the potential to establish settlements with agricultural economics26. As we know, the nomads are engaged in business activities in places called caravans or caravanserai, and sometimes also as commercial caravans at the time of migration, that means their livestock are sometimes traded as merchandise or sometimesthey are trading as tradespeople27. It should be mentioned that a number of sites located in the Zagros valleys are similar to this cluster are large but they have little attraction for residence and their local culture continues to flourish28. Considering what was said and very important settlement location of the Kholak and Kouganak, it seems that these sites are settlements that are related to commercial and agricultural activities at a low level.

Settlement pattern C

This settlement pattern consists of one site called Kopolikolah(code 414) (Figure 5), located at an altitude of 2232 meters above sea level. The site is located 70 meters from the communication path and 24 meters from the permanent water resources. The area of this site is 5600 meters and its slope is 9 degrees with direction of the eastern slope, and in terms of vegetation is located in pasture and poordry farming lands.The site is also similar to the pattern A considering the height from sea level, the breadth, the slope degree, the distance from the water resources and the communication paths, and the only factor that makes it stand in a separate pattern is its greater extent than the other sites in the settlement pattern A. Generally, these seasonal sites located in outlying regions are called “solitary site” which are made up of a few families29.

Regarding the central places and hierarchy of the Laran district, it should be noted that the theory of the central place of the Christaller does not apply in this field, because according to this theory, in each geographic area of a region, one of the population centers is larger than the other centers, and the number of goods and services is supplied in the center, is more than the other peripheral centers. Although this pattern can be surveyed in regions without natural obstacles and enclosing factors such as mountains, valleys, large rivers and deserts that prevent the dispersion of places, although the vast expanse of a site can not only be an absolute indicator for determining a place is considered as a central place, but it can be considered as an important factor in determining a central place. In late Chalcolithic in the central Zagros30, Islamabad31, Huleilan32, the highlands of the edge of Susa plain such as Izeh33, and Susa, also have a three-rank pattern similar to Laran, and include large, medium and small sites34, in this regions, Large sites such as Susa, covering about 11 hectares in this period, as a central site, average sites of 2 to 4 hectares are considered as small villages and small sites less than one hectare are considered seasonal. While all sites of the Laran district have an area of less than one hectare. The largest of them is the Kouganak and Kholak with an area of less than one hectare and, given the above, cannot be called a major central place such as the sites of Khuzestan plain. As we know, in the mountainous region, especially in the studied area, the relationships between the sites are more of an intra-regional type because of the distances between them, although the extra-regional type is also seen.In this way, most of the sites are centralized and the system of these sites is basically anethnical-tribal type. For this reason, habitants of such sites generally have inter-tribal relationships. The evidence of this type of relationship is best appeared in the standardization of their ceramics, which the author has observed among standard ceramics of Laran district. In Zagros studies, sites with less than one hectare with a geographic perspective, along with similar sites, have been considered as seasonal sites for nomads35. According to Zagarell studies in the Bakhtiari valleys, these types of settlements are usually similar to similar pottery findings, which have also regional correlations, and are kinship settlement, and sites such as the Kouganak, from which the beveled-rim pottery have been obtained, and in terms of Location are located alongside the main communication paths, calledsites with local centrality36.

With regard to the above, it can be concluded that the late Chalcolithic period of the Laran district are ethnical-tribal according to the centralized pattern. For this reason, habitants of such sites generally have inter ethnical-tribal relationships. In the writer’s studies in the region, similar to these inter ethnical and tribal relations among the Bakhtiari tribes, they are similar in terms of the settlement system with the settlement patterns of the Chalcolithic of the region.As mentioned, the Bakhtiari are one of the largest tribes in Iran, In the past not so long ago, thehierarchy of Bakhtiari tribe, unlike other nomadic societies, consisted of several levels and layers, some of which are still part of the Bakhtiari tribes today. According to Johnson’s research, in addition to the class system within a tribe, the size of the nomadic settlement site can also indicate the level of complexity and hierarchy of them, which means that the larger the size of these sites, they have more population and more complex hierarchy37. The Bakhtiari tribe social structure, from the hierarchy, follows a systematic and accurate traditional system that has a kind of constructive and functional relationship between branches based on the links and correlations of blood, relative, affinityor economic and live in a geographical area belonging to the tribe38. However, what is important is the difference between the great tribe with other people that this phenomenon appears among the nomadic population in the extent of the pastures, the number of flocks and the number of tribe people, and ultimately in the area of the settlement39, which are not only signs of power, but also a sign of wealth. The members of this group have a special economic and social position, as they have economically most agricultural land, desirable pastures and springs40. These people usually live in the settlements that are relatively bigger than other members. Another factor that leads to the rise of power or the appearance of leadership in the tribe is the limitation of the number of natural communication paths that formerly were from the deep valleys bed and in the river course41 and in the Southwest of Iran under the control of the BakhtiariIlkhanand Qashqai, and the Ilkhan had a great desire to control and commercially use these routes42. Compared to other tribes, the Bakhtiari have succeeded in developing and evolution a relatively complex social and economic system that was only one step up to the formation of the government, that means they reached a level of social complexity that maybe call it government with in the government43. Although there is no evidence of social complications from the archaeological excavations of the region, one of the most important signs of this complexity is the presence of beveled rim pottery, which is one of the signs of complexity in the lowlands44. It is also found on the Kouganak mound, and it seems that during this period, the nomads were controlling important communication routes between the central plateau and Khuzestan that crossed the area45; therefore, given the above, it can be said that Kouganak is a seasonal settlement that is located alongside the main route, and this route is probably controlled by nomads.

Conclusion

Christaller beliefs about hierarchical system of habitat relies more on commercial and transportation principles. These habitats are categorized at the national level into higher-ranking, lowerranking, the lowest-ranking, and certain central places. Then, the centrality of a place reflects its relative importance in ranking of hierarchy. The basis of Christaller theory is based on the order of number, size, distance and spatial arrangement of the central places according to their function and hierarchy in their habitat. Christaller believes that central places can be the result of the separation of socio-political or cultural issues. Major administrative centers and their subsidiaries are designed for administrative facilities that do not necessarily follow economic logic. In the same way, border towns that are largely built for defense purposes are settled in such a way that they do not have much sphere of influence. Regardless of these issues, the Christaller implements his viewpoint in a flat plain, while urban and rural settlements in their limited area have many physical and natural barriers to development, affecting environmental and topographical factors, while taking into account a flat region is one of the necessities of this theory. According to the above descriptions, it is not possible to justify the hierarchy patterns between the ancient sites of Laran County according to the pattern of the central place and hierarchy of Christaller, but it can be justified on the basis of the social and political structure by the allegory method in the region itself. The social and political structure of the Bakhtiari tribe in terms of hierarchy follows a traditional and accurate system and is based on the connections and correlations of the blood, relative or affinity, and economic that they have and living in a geographical limited area.The study of hierarchy and the central place of the sites ofthemiddle and late Chalcolithic period of the Laran district indicate that in the middle Chalcolithic period, like in other adjacent regions of the area, there is a two-rank pattern, and in the late Chalcolithic period, a three-rank pattern of that are similar to the present-day settlements in the region.Today, in theLaran district, the towns of Sudejan are located in the north and Sureshjan in the south of the region, which are considered to be the largest residential areas and are at the apex of the hierarchy pyramid. The remarkable thing is that the two Kouganak and Kholak sites, which are the largest sites of the Laran district, are located far away from these two cities. The second rank among the cities and villages of today Laran district is the newly established Haruni (the old big village), which still located next to the second rank site is called KopoliKolah with an area of half a hectare.Other villages in the Laran district are in the lowest rank or rank 3, which are similar to the same pattern among the Laran district sites with an area of less than 3000 square meters. In general, it seems that the Laran district, in accordance with its environmental conditions, in the prehistoric periods, synchronizedwith other Zagros valleyshas passed its cultural developments.

References

- Abdi K (1999a) “Archaeological research in Iran’s Islamabad Plain”. Journal of the Inter-national Institute of the University of Michigan 7: 8-11.

- Abdi K (1999b) “Archaeological research in the Islamabad Plain, Central Western Zagros Mountains: Preliminary results of the first season, 1998”. Iran 37: 33-43.

- Abdi K, Nokandeh G, Azadi A, Biglari F, Heydari S, et al. (2002) “TuwahKhoshkeh: A Middle Chalcolithic pastoralist camp-site in the Islamabad Plain, West Central Zagros Mountains, Iran”. Iran 40: 43-74.

- Abdi K (2003) “The Early Development of Pastoralism in the Central Zagros Mountains”. Journal of World Prehistory 4: 395-448.

- Alden JR, Heskel D, Hodges R, Johnson GA, Kohl PL, et al. (1982) “Trade and Politics in Proto-Elamite Iran”. Current Anthropology 6: 613-640.

- Algaze G (1993) The Uruk World System: The Dynamics of expansion of early Mesopotamian civilization, Chicago. The University of Chicago Press, USA.

- Alizadeh A (1992) “Reflecting the Geographical, Environmental, and Economic Role in Developments in Southwest Iran”. Asar 2: 29-49.

- Alizadeh A (1997) “A Preliminary Descriptive Report of Anthropological Archaeological Surveys in the Kur River Valleys and Northwest of Marvdasht Fars”. Archaeological Reports 1: 67-88.

- Alizadeh A (2010) “the Rise of the Highland Elamite State in Southwestern Iran”. Current Anthropology 51: 353-383.

- Alizadeh A (2013) “Combination of contradictory and complementary subsistence: Nomadic Agriculture and livestock in southwest Iran”. Iranian Journal of Archeology 3: 41-73.

- Bahraminia M, Khosrowzadeh A, EsmaeiliJelodar ME (2014) “Analysis of the Role of Environmental Factors in the Spatial Distribution of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic Sites of Ardal County, Chaharmahal VA Bakhtiari Province”. Pazhohesh ha-yeBastanshenasi Iran 5: 21-37.

- Barth F(1964) Capital and the Social Structure of a Pastoral Nomad Group in South Persia.In Capital, Savings and Credit in Peasant Societies .Edited by R Firth Aldin & BS Yamey PP. 69-81.

- Blench R (2001) Pastoralists in the new millennium. Overseas Development Institute, London.

- Brown S, Christaller K (1995) New My Father: Recycling Central Place Theory. Journal of Macromarketing 15(1): 60-72.

- Carr M (2003) New Patterns: Process and Change in Human Geography. Tomas Nelson, United Kingdom.

- Digard JP (1981) Techniques des nomadesbaxtyârid'Iran. CUP, Cambridge, England.

- Duffy PR (2015) “Site size hierarchy in middle- range societies”. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 37: 85-99.

- Gamble C (2001) Archaeology: The Basic. Taylor & Francis Library, London.

- Grant J, Gorin S, Fleming N (2002) The Archaeology Coursebook. Routledge, London.

- Garajian O (2003) “A critique of the theoretical function and the central place model in archeology and the design of a method with using toethnoarchaeology. Archaeological Reports 2: 173-188.

- Henrickson EF (1985) “Early development of Pastoralism in the central Zagros Highlands (Luristan)”. Iranica Antiqua 12: 1-43.

- Henrickson EF (1994) “the Outer limit: Settlement and Economics Strategies in the Central Zagros Highland During the Uruk Era”, in Chiefdoms and Early States in the Near East, the Organizational Dynamics of Complexity. Monograph in World Archaeology, edited by Stin G & Rothman M. Madison Wisconsin, USA, pp. 85-102.

- Hole F (1980) “Archaeological survey in Southwest Asia”. Paléorient 6: 21- 44.

- Hole F (1987) “Archaeology of the Village Period”, in The Archaeology of Western Iran. edited by Frank Hole, Smithsonian press, Washington, USA.

- Inomata T, Aoyama K (1996) “Central-Place Analyses in the la Entrada Region, Honduras: Implications for Understandingthe Classic Maya Political and Economic Systems”. American Antiquity 7: 291-312.

- Johnson GA (1983) “Decision-Making Organization and Pastoral Nomad Camp Size”. Human Ecology 11: 175-199.

- Khosrowzade A (2015) “The Chalcolithic Period in the Bakhtiyāri Highlands: Recently-discovered Sites in Fārsān, ChāhārMahālvaBakhtiyāri, Iran”. International Journal of the Society of Iranian Archaeologists 1: 71-92.

- Minc LD (2006) “monitoring Regional Market Systems in Prehistory: Models, Methods and Metrics”. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 25: 82-116.

- Mortensen P (1974) “a survey of prehistoric settlements in northern Luristan”. ActaArchaeologica 45: 1-47.

- Nakoinz O (2012) “Models of Centrality, etopoi”. Journal of Ancient Studies 3: 217- 223.

- Saydaei E, Dehghan A (2011) “the Role Peoples Participation in Rural Development: With Emphasis on Traditional and New participation”. Journal of Applied Sociology 21: 1-18.

- Silverman H (2002) Ancient Nasca Settlement and Society . University of Lowa Press, India.

- Wright Henry (1987) “the Susiana Hinterlands during the Era of Primary state Formation”, in the archeology of western Iran: Settlement and Society from Prehistory to the Islamic Conquest. edited by Frank Hole, Smithsonian Series in Archaeological Inquiry, Washington , USA pp: 140- 155.

- Zagarell A (1975a) An Archaeological Survey in the North-east Baxtiari Mountains. proceeding of the IIIrd. Annual Symposium of Archaeological Research in Iran. pp 23-30.

- Zagarell A (1975b) Nomad and settled in the Bakhtiari Mountains, Sociologus 25: 127-138.

- Zagarell A (1982) the Prehistory of the Northeast Bahtiari Mountains, Iran: The Rise of Highland Way of Life. Beihefte Zum Tubinger Atlas des Vordern Orients;Riehe BWeisbaden, Germany.

- Zagarell A (1989) “Pastoralism and the early state in Greater Mesopotamia”, in Archaeological thought in America. Edited by C Lamberg- Karlovsky. Cambridge University Press, England pp. 280-301.

1Inomata and Aoyama 1996.

2Nakoinz, 2012.

3Brown 1995.

4Nakoinz 2012.

5Inomata and Aoyama 1996.

6Hole 1980, p. 29.

7Garajian 2003.

8Minc 2006.

9Brown 1995.

10Garajian 2003.

11Gamble 2001, p. 145.

12Silverman 2002, p. 7.

13Hole 1980; Duffy 2015.

14Inomata and Aoyama 1996; Grant et.al2002, p. 175.

15Alizadeh 2010, p. 372.

16Alizadeh 2013.

17Garajian 2003.

18Carr 2003, p. 125.

19Alizadeh 2010, p. 364.

20Zagarell1989.

21Hole 1987.

22Barth 1964.

23Saydaei and Dehqani 2011, p. 15.

24Zagarell 1982, p. 64.

25Algaze 1993, p. 63.

26Bahraminia et al. 2014.

27Blench 2001, p. 14.

28Henrickson 1994.

29Zagarell1989.

30Henrickson 1985.

31Abdi 2003.

32Mortensen 1974.

33Wright 1987, Fig. 33a.

34Alden et al 1982.

35Abdi 1999a, 1999b, 2002; Abdi et al 2002, 2003; Zagarell 1975a, 1975b, 1982, 1989.

36Zagarell 1989.

37Johnson 1983.

38Digard 1981, p. 63.

39Barth 1964.

40Seydayi and Dehqan 2011, p. 15.

41Alizadeh 1997.

42Alizadeh 1992.

43Alizadeh 2010, P. 354.

44Zagarell 1989.

45Khosrozadeh 2015.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...