Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Mini Review(ISSN: 2690-5752)

The Heidelberg Model of Traditional Chinese Medicine-A Systematic View on Emotions Volume 7 - Issue 3

Maria João Santos*

- ICBAS-Institute of Biomedical Sciences Abel Salazar, University of Porto, Portugal

Received:November 28, 2022; Published: December 09, 2022

Corresponding author: Maria João Santos, ICBAS-Institute of Biomedical Sciences Abel Salazar, University of Porto, Portugal

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2022.07.000264

Introduction

Since antiquity, the scientific community has discussed the role of emotions in life and human health [1]. The development of bioengineering and neuroscience allowed us to glimpse the monistic mind-body relationship of the human being, which was confirmed with the interaction between the organic (including vegetative changes) and psychological dimensions of the humans [2-4]. Nowadays, models of emotional processing, such as the model proposed by the neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, assume that emotions are reflected in the body, and they have a crucial action in the coordination of behavior and physiological states during the events [5-9]. The current scientific evidence suggests that changes of state of the body are mapped topographically in the central nervous system (CNS) and are triggers for corrective physiological responses. These answers are interrupted when the homeostatic deviation has been rectified [6]. As stated by António Damásio, the awareness of emotions is based on the neural representation of bodily cognitions, with ‘somatic markers’ evoking feeling states that influence cognition and behavior [10,11]. Emotions arise, prevail, and mobilize this complex neural mechanism. They directly report the beneficial or disadvantageous nature of a physiological event that facilitates learning of the conditions that led to homeostatic imbalances and their respective corrections, allowing future anticipation of adverse (withdraw) or favorable conditions (approach) [6].

Traditional Chinese Medicine

Figure 1: Sinusoidal curve of postulated physiological mechanisms of the phases and vegetative functional mechanisms (adapted from Greten 2017).

For thousands of years, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) recognized emotions as part of patterns, in a continuum among body, biotypology and mind, which lead to systemic functional diagnosis and treatment strategies. The so-called Heidelberg’s model (HM) of TCM, defines it as a system of findings and sensations designed to establish the patient’s functional vegetative state [12]. In this model, the classic concepts of TCM are integrated into the knowledge of Western medicine [13,14]. The circular description of lifelong regulation processes is described throughout a sinusoidal curve and by analogy with human physiology, the “phases” (or elements) are described as vectors of physiological and functional action, in which the “earth phase” assumes the homeostatic target value (Figure 1).

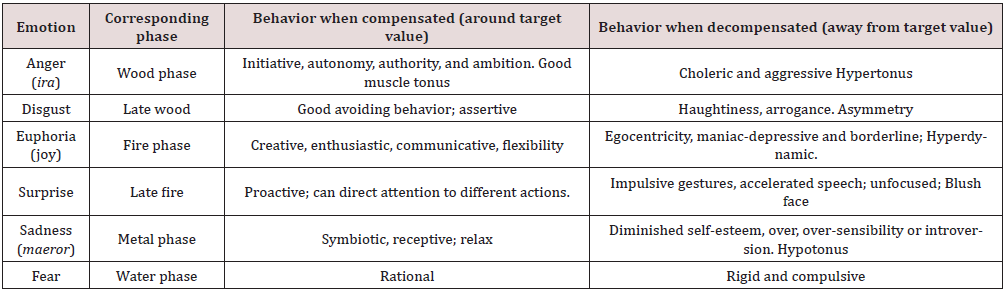

In terms of vegetative action, in the yang phases, sympathetic functions dominate more than in the yin phases whereas in the yin phases, parasympathetic activity is relatively more present (Figure 1) [13,15]. The application of this cybernetic model to the autonomic nervous system, results in a categorization of “organic patterns” called “orbs” (equivalent to Zang-Fu), a physiological response with neurovegetative origin [15,16]. In TCM, each “orb” is related to regions of the body, a somatotopic representation. Thus, each “phase”, “orb” and the corresponding emotion, will manifest itself in accordance with its characteristics in different somatotopic areas of the body, which reminds us of Carl G. Carus’ theory about constitutions. Therefore, TCM is essentially based on a system that describes functional anomalies through the analysis of signs and symptoms that arise from neurovegetative activity, also reporting the bio-psycho-behavioral activity (Table 1). The HM of TCM conceptualizes emotions as neuro-emotional vectors of the “phases”, which reflect a vegetative experience of being, exerting a network role in the overall of mental impulses [13,15,17] where emotions consist of vectorial movements arising from the center, (“e-motion”) expressing a certain “phase”, a vegetative functional tendency (Figure 2) [13]. Moreover, an emotion is the component that comes out of actions, whereas a feeling is the component that comes out of our perspective on those actions [13]. In addition, emotions are an integral part of reasoning and decision-making processes [18,19]. Paraphrasing, Henry Greten (2012), “emotions are vectorial movements that reflect the vegetative experience of being, and in turn interact globally and dynamically with neuro-cortical impulses” [20] (Figures 2 & 3). Within this system of the phases, a coordinate system of emotions can be elaborated (13), a two-part system of behavioral action and inhibition may be discriminated (Figures 2 & 3) as well as the analysis of compensated or decompensated behavioral manifestations of each “phase” (Table 1).

Figure 2: Emotion as a vectorial movement that arises from the center, in a direct relationship with the regulatory system of the phases. The homeostatic target value corresponds to the “earth” phase (Greten 2007).

Conclusion

In conclusion, there are numerous analogies between the Chinese classic model of emotionality and modern western psychology and neurophysiology. Considering the recent theories about emotions and the theories of TCM, especially the HM, we realize that the common points are more than the differences between the western/allopathic and eastern/holistic models of human health. In fact, in recent years these models tend to converge in their conceptions of emotions. This realization leads us to believe that future comparative studies should be carried out, as they will most probably allow a better understanding of the human mind.

References

- Hammer L (2002) Psicología y Medicina China. La Ascensión del dragón el vuelo del pájaro rojo. La liebre de marzo. Barcelona 1-19.

- Damásio AR (1999&2000) The feeling of what happens. Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. Harcout, New York, United States.

- Phelps EA, Delgado MR, Nearing KI, Le Doux JE (2004) Extinction learning in humans: role of amygdala and vmPFC. Neuron 43(6): 897-905.

- Craig AD (2008) Interoception and emotion: a neuroanatomical perspective In MD Lewis, JM Haviland Jones, LF Barrett (Eds), Handbook of emotions. The Guilford Press, New York, United States pp. 272-290.

- Craig AD (2002) How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nature reviews-Neuroscience 3(8): 655-666.

- Damasio AR, Carvalho GB (2013) The nature of feelings: evolutionary and neurobiological origins. Nature-Neuroscience 14(2): 143-152.

- Nummenmaa L, Enrico Glerean, Riitta Hari, Jari K Hietanen (2014) Bodily maps of emotions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111(2): 646-651.

- Regard J (2014) As emoções Simplesmente. Épigenese desenvolvimento e psicologia. Edições Piaget.

- Colombetti G, Evan Thompson (forthcoming) The Feeling Body: Towards an Enactive Approach to Emotion. In WF Overton, U Mueller, J Newman (eds.), Body in Mind, Mind in Body: Developmental Perspectives on Embodiment and Consciousness. Erlbaum.

- Bechara A, Damasio AR (2005) The somatic marker hypothesis: A neural theory of economic decision. Games and Economic Behavior 52(2): 336-372.

- Füstos J, Gramann K, Herbert BM, Pollatos O (2012) On the embodiment of emotion regulation: interoceptive awareness facilitates reappraisal. SCAN 8(8): 911-917.

- Greten HJ (2007) Kursbuch Traditionelle Chinesische Medizin. Thieme, Stuttgart, Germany pp. 1-696.

- Greten HJ (2017) Understanding TCM. The fundamentals of Chinese Medicine, Part I. Heidelberg School Edition, Heidelberg, Germany.

- Porkert M, Hempen Carl Hermann (1995) Classical Acupunture: The standard book. Phainon, Germany.

- Paiva C, Greten HJ (2012) Constitution and emotion-an east-western comparison. Can we parameterize TCM diagnostic criteria? Tese de Mestrado em Medicina Tradicional Chinesa. Universidade do Porto, Portugal.

- Ponte Sara, Greten HJ (2015) Potenciais efeitos do qigong médico na perturbação depressiva major.Tese de mestrado em medicina tradicional chinesa. Universidade do porto, Portugal.

- Ana Sofia, P Sousa, Greten HJ (2015) First steps towards a TCM-based music therapy. Vegetative Functions Induced by Music. Tese de Mestrado em Medicina Tradicional Chinesa. Universidade do Porto, Portugal.

- Reis Deidre L, Jeremy R Gray (2009) Affect and action control. Oxford Handbook of Human Action. Oxford University Press, Oxford pp. 277-297.

- Damasio Antonio (2003) Feelings of emotion and the self. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1001(1): 253-261.

- Greten H J (2012) From ancient Chinese medicine to Heidelberg model of TCM: Mental-emotion states, Personal communication (July 2012, ICBAS-University of Porto), Portugal.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...