Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Opinion Article(ISSN: 2690-5752)

The Choice of Cultural Violence or Cultural Peace Volume 9 - Issue 4

David Whippy*

Intercultural Peacebuilding Program, Faculty of Culture, Languages and Performing Arts, Brigham Young University, Hawaii

Received: June 03, 2024; Published: June 18, 2024

Corresponding author: Intercultural Peacebuilding Program, Faculty of Culture, Languages and Performing Arts, Brigham Young University, Hawaii

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2024.09.000316

Introduction

The catchphrase “wake up and choose violence” was a popular tagline on social media a few years ago, usually indicating someone being mean and comically insulting another. However, the fact that there is truth in the idiom is no laughing matter. We, as human beings have the choice to choose violence or peace every day. Unfortunately, many of us choose violence. But how are we choosing violence over peace? The premise is a difficult one to fathom because it challenges our self-image of good, upstanding, and responsible ideals. One could argue that the choice for violence is made unconsciously and unintentionally, or that violence is necessary for peace, or that violence is uniquely framed for the culture. These points are valid and can be easily justified in the academic literature. However, this piece invites readers to ‘wake up’and make the conscious decision to choose peace in our diverse cultures.

Our choice between violence or peace is significantly framed by our culture. Within the extensive reservoir of definitions that social scientists use to explain culture, I will subscribe to Chris Jenk’s contribution to the field as the standard-bearer of the piece; culture is a cognitive social way of being, invoking collective intellectual and moral development in an identified society with its values, symbols, arts, and practices [1]. In layman’s terms, it’s the mental, emotional, and social lens through which a group of people sees, comprehends, and engages with the world around them. Culture shapes, connects, and gives meaning. At an individual level, it prescribes rules that unconsciously guide our thoughts and behavior. All our actions are shaped by our culture and the culture wherein they are enacted [2]. This viewpoint supports the narrative that we as human beings are products of our culture. Further adding to the complexity of culture are the constituent integrated parts that make up the whole. Religion, traditional customs, education, language, political and economic philosophy, science, and the arts are some parts of holistic culture. Viewing culture as an integrated system allows us to recognize how cultural traits fit the cohesive whole while facilitating understanding and meaning within the environment [3]. Culture is living, dynamic, and versatile. Moreover, it is in a state of constant change as we live our lives, navigating and negotiating values, beliefs, symbols, and meaning within different cultural spaces. Culture influences behaviour and when connected to violence, can justify its violent existence or undermine the validity of violence.

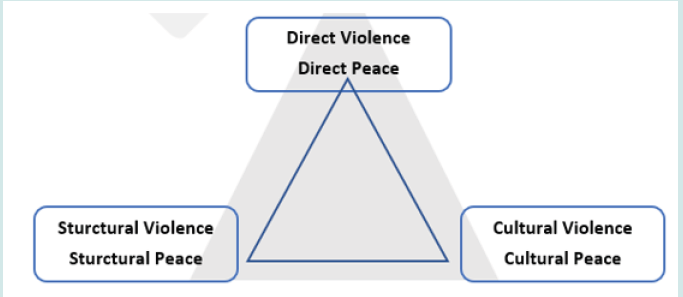

Figure 1: Visual representation of the Galtung’s conceptual triangular interplay of violence and peace.

Johan Galtung conceived of the triangular representation of cultural, structural, and direct violence [4]. He frames cultural violence as character traits from parts of culture that justify and legitimize direct and structural violence in society. In Galtung’s perspective, cultural violence encompasses the biases, negative narratives, assumptions, attitudes, and beliefs that we internalize. Our way of being, or how we choose to see others, is influenced by the integrated parts of culture as listed previously: religion, traditional customs, education, language, political and economic philosophy among others. The perspective is violent because it gives life to the discourse in individuals and communities the prevailing outlook that violence towards others, especially those we associate with outgroups, is normal and justified. When we embrace cultural violence, it’s ‘natural’ to implement and support legislation that discriminates, segregates, and favors a specific ethnic or religious group (structural violence). Cultural violence makes it easier to be racist, sexist, and xenophobic. When humans are culturally violent, it’s ‘right’ to engage in bullying, hate speech, domestic and sexual violence, and emotional manipulation (direct violence). In this way of being, others ‘deserve’ to be treated in this violent manner because my cultural bearings justify my actions towards them. This negative spiral shows how cultures can perpetuate violence, further manifesting itself in structural and direct violence. At its core in these circumstances, our cultures breed violence. The position is difficult to accept or even believe that a significant component of what makes us human can also be the root of violence towards others. As human beings, I believe that we are not inherently violent, but our culture and the behavior it dictates can lead to violent tendencies. It’s fortunate for us that our cultures can also influence peace.

Cultural peace is the opposite of cultural violence. It embodies components of culture that justify and can be used to build peace. Furthermore, cultural peace increases the probability of structural and direct peace. Cultural peace “engenders structural peace, with symbiotic, equitable relations among diverse partners, and direct peace with acts of cooperation, friendliness and love” [5]. Important cultural components include recognition of the tenets of nonviolence, respect, humanization, inclusiveness and the promotion of social justice, harmony, equality, and equity. These principles and beliefs are representations of the integrated components of culture and are grounded in religion, traditional culture, education, philosophy, and art. When these influence the values, attitudes and behaviours of individuals and communities, peace conditions become the norm. An example of this is the commonly held discourse in Christianity, that all humans are brothers and sisters. This religious-cultural belief then informs peaceable engagement around human rights, equity and equality (structural peace) and relationships built on respect, trust, collaboration and an understanding of the common good (direct peace). This way of being prescribes that we see and treat others in ways that is conducive to peace in the context. At its core, our cultures can invite peace. Closely connected to cultural peace is a Culture of Peace. Coined and adopted in resolution by the United Nations General Assembly in 1989, it is defined as the: …values, attitudes and behaviours that reflect and inspire social interaction and sharing based on the principles of freedom, justice and democracy, all human rights, tolerance and solidarity, that reject violence and endeavour to prevent conflicts by tackling their root causes to solve problems through dialogue and negotiation and that guarantee the full exercise of all rights and the means to participate fully in the development process of their society.

The development of a culture of peace starts with a foundation of cultural peace. Only through a balanced triangular interplay of cultural peace, structural peace and direct peace can a culture of peace be fully recognized.

Culture is living and dynamic. As we move through life gaining experience and education, our cultures influence how we see and engage with the world. We can focus on and prioritize cultural components that lead to violence or emphasize attributes that lead to peace. While the consequences of cultural violence can be harder to identify and acknowledge, they can be limited, managed, and stopped by actively seeking cultural peace. It’s paradoxical to think that culture can lead to violence and can also lead to peace. This conflict is the challenge and the opportunity of culture in building peace. If cultural violence leads to structural violence and peace and direct peace, then cultural peace can lead to structural violence and direct violence. To build a culture of peace, we as human beings need to consciously liberate ourselves from the tendencies of cultural violence and embrace the tenets of cultural peace. These cultural shifts are difficult to make because it requires self-reflection and self-analysis of our own cultures, in identifying the prevalent violent aspects. Beyond recognition and acknowledgement, the transition requires us to actively engage with the relevant stakeholders to eradicate characteristics of cultural violence and promote those that highlight cultural peace. This is commonly done through education, training, and awareness and advocacy campaigns at the grassroots through the governingleadership levels. In conclusion, I hope this article serves as an open invitation to readers to better acquaint themselves with their cultures, make the necessary changes if needed, and to consistently choose peace.

References

- Jenks Chris (2004) Culture. Taylor & Francis pp. 11-12.

- Walker Polly O (2004) "Decolonizing conflict resolution: Addressing the ontological violence of westernization." American Indian Quarterly 28(3): 527-549.

- Spencer Oatey Helen and Peter Franklin (2012) "What is culture." A compilation of quotations. GlobalPAD Core Concepts 1 no. 22 (1): 1-21.

- Galtung J (1990) Cultural violence. Journal of Peace Research 27(3): 291-305.

- Ibid, p 302.

- General Assembly resolution 52/13. 1998. Culture of peace, A/52/L.4/Rev.1 and Add.1. Accessed May 20, 2024.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...