Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Short Communication(ISSN: 2690-5752)

Technoculture and Language Models in Archaeology: Reconstructing and Preserving Cultural Narratives Through Digital Humanities Volume 10 - Issue 1

James Hutson*

Department of Art History, AI, and Visual Culture, Lindenwood University, USA

Received: September 14, 2024; Published: September 25, 2024

Corresponding author: James Hutson, Department of Art History, AI, and Visual Culture, Lindenwood University, USA

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2024.10.000328

Abstract

Technoculture, which examines the intersection of culture and technology, has increasingly permeated archaeological practice, transforming both scholarly research and public engagement [1-3]. The introduction of digital tools such as virtual reality (VR), geographic information systems (GIS), and large language models (LLMs) has democratized access to archaeological knowledge, enabling communities to engage more actively with their cultural heritage [4-6]. This short article explores the mutual influence of technocultural studies and AI technologies on archaeology, with a focus on the preservation and reconstruction of cultural narratives through digital means.

Keywords: Shambala, Buddhism; Time Wheel; Kalachakra; Sex Tantra; Union Practice; Trantrayana; Holy Bible

Technoculture and Public Engagement

Technoculture in archaeology emphasizes the reciprocal relationship between technological innovation and cultural expression. Digital tools such as GIS have been pivotal in the spatial analysis of archaeological sites, but their utility extends beyond research [10]. Through public-facing projects, communities can engage with GIS data, contribute local knowledge, and offer interpretations that reflect contemporary cultural values. A notable example of VR and GIS-based platforms allowing communities to engage with cultural heritage beyond traditional museums is the reconstruction of the Roman arch of Palmyra, Syria, destroyed by ISIS. Through the collaboration of institutions like Oxford and Harvard, the Institute of Digital Archaeology developed a 3D virtual model of the arch based on photographs taken by archaeologists and tourists before its destruction. This model was later transformed into a physical replica, carved in marble using robotic technology [11]. The virtual recreation of the arch not only preserves public memory but also provides a medium for communities worldwide to experience and engage with this cultural heritage site virtually. This demonstrates the potential of digital technologies, such as VR, in the preservation and dissemination of historical artifacts, especially in cases where the original sites are at risk of destruction or are inaccessible due to conflict.

Moreover, projects like Open Heritage by Google Arts & Culture expand this engagement by offering 3D views of significant world heritage sites, thus democratizing access to cultural history [12]. These digital initiatives not only preserve artifacts but also invite broader participation, allowing communities to contribute to the interpretation of their heritage, thus fostering a more inclusive dialogue around cultural preservation. This approach aligns with the concept of participatory GIS, where community knowledge and contributions are integrated into the mapping and interpretation of heritage sites. For example, participatory mapping projects have empowered indigenous communities to contribute land-related knowledge, thus reshaping the dialogue around cultural patrimony [13].

Furthermore, with the widespread availability of 3D scanning technologies, this potential of these technologies to bring communities into the dialogue is now more accessible than ever to non-specialists. Devices like iPhones and iPads (generation 10 and later) are now equipped with LiDAR, enabling users to easily capture detailed 3D models. Additionally, numerous free apps allow users to scan and upload 3D models, contributing to the broader sharing and interpretation of heritage [14]. This democratization of technology allows communities and individuals to participate in cultural preservation, creating a more participatory and inclusive approach to heritage management.

LLMs and the Preservation of Endangered Languages

While technocultural tools are reshaping public engagement with artifacts, LLMs are playing an equally influential role in preserving the languages associated with those artifacts [15]. Language is a crucial element in understanding the cultural significance of archaeological finds, and many world languages— particularly indigenous and minority languages—are under threat [16]. LLMs such as GPT-4, trained on vast amounts of data, can model these endangered languages, helping to reconstruct lost grammatical structures, vocabularies, and idiomatic expressions. A compelling example of this is the Endangered Languages Project [17], an initiative, which allows public participation, focuses on documenting and providing resources for the preservation of nearly 3,500 endangered languages worldwide. It offers a platform where linguists, researchers, and community members can upload resources, including audio samples, dictionaries, and texts, that contribute to language revitalization efforts. This openaccess project is supported by a global coalition that includes the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa and other institutions, ensuring a collaborative effort in preserving linguistic diversity.

This linguistic preservation is essential for maintaining the integrity of cultural heritage. Many artifacts, from ancient manuscripts to oral traditions passed down over generations, are tied to specific linguistic contexts. Through these new AI-powered technologies to reconstruct these languages, archaeologists can better interpret the cultural narratives embedded in these artifacts, providing a richer understanding of the societies that produced them. Additionally, AI-driven preservation can offer a resource for the descendants of these communities, ensuring that their linguistic heritage is not lost to history.

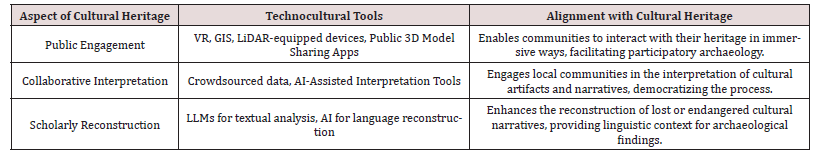

A Framework for Digital Heritage Technoculture

While both technoculture and LLMs have been used in anthropological and archeological contexts, brining the two together to inform a more holistic understanding of culture has yet to materialize. As such, the proposed framework here calls for a Digital Heritage Technoculture (Table 1), a comprehensive framework for preserving and understanding cultural heritage. By bringing together modern technologies such as AI-driven LLMs, VR, and GIS, this framework allows for both the physical and ephemeral aspects of culture to be documented, analyzed, and shared. On the one hand, 3D scanning, LiDAR-equipped devices, and GIS technologies provide a means for non-specialists and professionals alike to create detailed, immersive models of archaeological sites and artifacts. These digital reconstructions enhance accessibility, enabling communities to engage directly with their heritage and allowing for a more inclusive dialogue in the interpretation of physical cultural remains.

Simultaneously, LLMs play a vital role in preserving the intangible elements of cultural heritage, such as endangered languages and oral traditions, which are often inseparable from the physical artifacts found in archaeological contexts. AI models trained on linguistic data can reconstruct and preserve languages that are critical to interpreting cultural practices, beliefs, and historical narratives embedded in material culture. These technologies, when combined, allow for a more holistic approach to archaeology—one that integrates both the physical remnants of past societies and the linguistic and cultural frameworks that gave them meaning. For instance, the collaboration between Te Hiku Media and other indigenous groups to preserve the Māori language through AI tools [18] demonstrates how language preservation efforts can complement archaeological work, particularly when artifacts carry inscriptions or oral histories that are tied to endangered languages.

This framework of Digital Heritage Technoculture reflects a new paradigm where the physical and ephemeral elements of culture are brought together through the power of modern technology. 3D models of sites and artifacts offer tangible, visual ways to explore heritage, while LLMs preserve the intangible knowledge that offers deeper context for these objects. Together, these tools allow archaeologists and communities to co-create a living archive of cultural heritage that evolves as more data is added and more voices contribute to the dialogue. This inclusive, multi-dimensional approach transforms heritage from a static collection of relics into a dynamic, participatory space that encompasses both the material and immaterial aspects of human history.

Conclusion

The integration of technocultural tools and LLMs into archaeological and anthropological practices marks a significant evolution in how cultural heritage is preserved, interpreted, and engaged with. Through the combination of advanced technologies such as 3D scanning, LiDAR, GIS, VR, and AI-driven language preservation, a holistic framework for Digital Heritage Technoculture emerges. The framework not only preserves the physical remnants of past civilizations but also safeguards the ephemeral elements—languages, oral histories, and cultural practices—that are critical to understanding the broader context of those artifacts.

These technologies have democratized access to cultural heritage, enabling both specialists and non-specialists to contribute to its preservation and interpretation. The empowerment of communities to actively participate in documenting and interpreting their heritage has motivated the field of archaeology to move away from static preservation and towards dynamic, collaborative engagement. The preservation of endangered languages through LLMs further enriches this dialogue, ensuring that the cultural knowledge encoded in language continues to provide essential context for physical artifacts. In sum, this approach bridges the tangible and intangible aspects of culture, creating a participatory and evolving space where both material artifacts and the narratives they carry are preserved for future generations. The alignment of technocultural innovations with AI-driven methodologies, proposed in this framework, holds demonstrable potential for the future of archaeology and cultural heritage preservation.

References

- Huhtamo E, Parikka J (2011) Media archaeology: Approaches, applications, and implications. Univ of California Press 16(6): 1-7.

- Kozinets R V (2022) Understanding technoculture. In The Routledge Handbook of Digital Consumption, Routledge pp. 152-165.

- Del Prado P T N (2024) Andean audiotactility: transcultural interfaces elucidating a divergent history of technology. Artnodes 34(1): 1-9.

- Smith M L, Newton C (2024) Cartographies of warfare in the Indian subcontinent: Contextualizing archaeological and historical analysis through big data approaches. Journal of Big Data 11(1): 120.

- Moorhouse B L, Li S S, Pahs S (2024) Teaching with Technology in the Social Sciences. Springer Nature 1-6.

- Li J, Zheng X, Watanabe I, Ochiai Y (2024) A systematic review of digital transformation technologies in museum exhibition. Computers in Human Behavior p.108407-108407.

- Leslie C (2023) Archeology of the future. In From Hyperspace to Hypertext: Masculinity, Globalization, and Their Discontents, Singapore, Springer Nature Singapore, pp.175-235.

- Ginn M, Hulden M, Palmer A (2024) Can we teach language models to gloss endangered languages? p. 1-14.

- Ehret C, Posnansky M (2023) The archaeological and linguistic reconstruction of African history. Univ of California Press.

- Menéndez Marsh F, Al-Rawi M, Fonte J, Dias R, Gonçalves L J, et al. (2023) Geographic information systems in archaeology: a systematic review. Journal of Computer Applications in Archaeology 6(1): 40-50.

- Davidson L R (2023) Cultural representation and digital reproduction: a critical analysis of post conflict reproductions of heritage. Doctoral dissertation.

- Butts S (2019) Stereoscopic rhetorics: model environments, 3D technologies, and decolonizing data collection. In Mediating Nature, Routledge pp. 46-65.

- Di Gessa S, Poole P, Bending T (2008) Participatory mapping as a tool for empowerment: Experiences and lessons learned from the ILC network. Rome, ILC/IFAD p. 45.

- Mikita T, Krausková D, Hrůza P, Cibulka M, Patočka Z (2022) Forestroad wearing course damage assessment possibilities with different types of laser scanning methods including new iPhone LiDAR scanning apps. Forests 13(11): 1763-1763.

- Zhang K, Choi Y, Song Z, He T, Wang W Y, et al. (2024) Hire a linguist!: learning endangered languages in LLMs with in-context linguistic descriptions. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics ACL 2024 pp. 15654-15669.

- Majidi A (2013) English as a global language: threat or opportunity for minority languages. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 4(11): 33-38.

- ELP (2024) Endangered languages project. Retrieved.

- Jones P L, Mahelona K, Duncan S, Leoni G (2023) Kia tangata whenua: Artificial intelligence that grows from the land and people.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...