Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Research Article(ISSN: 2690-5752)

Striking Correspondences Between Plato’s Atlantis and Greenland Volume 10 - Issue 3

Felice Vinci*

Senior Research Fellow of ATINER, Italy

Received: February 4, 2025; Published: February 11, 2025

Corresponding author: Felice Vinci, Senior Research Fellow of ATINER, Italy

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2025.10.000339

Abstract

Ever since Plato in two of his Dialogues dwelt on a civilization born on a large island in the Atlantic, which in ancient times would have become master of the seas and then tragically disappeared, there have been discussions on the veracity of his story. In this article we will try to demonstrate that in reality there are many, convergent and detailed proofs of the real existence of Atlantis, which lead to its unequivocal identification with Greenland, the largest island in the world: the geographical position, the dimensions, the peculiar morphology, the mineral resources, and much more. Furthermore, it is no coincidence that this evidence is at least in part emerging right now. In fact, even if the first proposal for the identification of Greenland dates back to the seventeenth century, only now have the effects of incipient Global Warming, together with technological developments, allowed us to gain a deeper understanding not only of the geography and geology of the Arctic island (which is still largely covered by a thick layer of ice), but also of the quality and importance of its mineral resources. In addition to the latter, what has recently brought Greenland to the forefront of world politics has been its strategic position, which is potentially extraordinary in the prospect that in a short time the Arctic Ocean will once again be navigable, as it was during the expansion—mainly by sea, as has been verified by recent studies—of the megalithic civilization, of which impressive traces are found throughout the world. The extraordinary parallels between the island described by Plato and the current reality of Greenland promise further surprises as the gradual melting of the current ice sheet continues.

Keywords: Atlantis; Greenland; Narayana; Plato; Timaeus; Critias; Global Warming; Holocene Climatic Optimum (HCO).

Introduction

In this article we will try to demonstrate that the characteristics, geographical and otherwise, attributed by Plato to the mythical island of Atlantis actually correspond to those of Greenland, the vast island located in the North Atlantic. Not only that: these characteristics, in particular its strategic geographical position combined with its mineral wealth, explain the interest of global powers such as the United States, China and Russia. To this end we will use a methodology consisting of a new critical examination of sources not only classical, but also belonging to other literary and scientific contexts.

Plato exposes the myth of Atlantis in two of his dialogues, the Timaeus and the Critias, starting from the moment in which Critias, one of the interlocutors of the Timaeus, begins to recount the content of a conversation, reported to him by his great-grandfather, that Solon had had with an Egyptian priest.

In this narrative, later extensively developed in the Critias, Plato focuses on a vast island where in ancient times an advanced civilization would have developed, master of the seas and capable of great engineering feats, which would have expanded with its ships on both sides of the Atlantic.

The possible existence of an authentic Atlantis was actively discussed during classical antiquity. Almost ignored in the Middle Ages, it was then rediscovered by humanists in the modern era, and inspired the utopian works of several Renaissance writers, such as Francis Bacon’s ‘New Atlantis’, while most present-day philologists and classicists agree on the story’s fictional nature [1].

Thousands of books and essays have been dedicated to the theme, with the most disparate proposals for its location. In particular, the first to propose the identification of Plato’s Atlantis with Greenland was the French writer François de la Mothe le Vayer (1588-1672), who was known to use the pseudonym Orosius Tubero, followed by others [2].

The myth of Atlantis represents one of the most famous and debated themes of classical mythology: “Is what Plato narrates true? This is the question of anyone who approaches the story of Atlantis” [3]. This is how Enrico Turolla (1896-1985), one of the greatest Greek scholars of the last century, introduces the myth of the disappeared island. According to him, the answer is undoubtedly positive: in fact, as he states immediately afterwards, Plato “is the bearer of a voice that comes from further away. He received, he arranged; he did not invent; indeed, he faithfully preserved, as the reference to the continent beyond the sea undoubtedly demonstrates”.

Here this scholar refers to the passage from the Timaeus in which Plato says that in the Atlantic, beyond that lost island, there are other islands, beyond which the ocean is surrounded by “a land that absolutely, undoubtedly, most correctly can be defined as a continent” [4]. Therefore, according to Turolla, the fact that a great philosopher like Plato, whose prose is usually elegant, moderate, free from overstatement, puts his credibility at stake by using even three consecutive adverbs [5] (the last of which in the superlative) to convince his readers of the existence of a continent overseas that in his time was completely unknown to the ancient Greeks, attests to the reliability of his statements, given that today we know well that that continent beyond the ocean really exists.

Let us then read the whole sentence which contains that reference to the continent beyond the sea which convinced Professor Turolla of the historical reliability of what Plato says about Atlantis:

“For the ocean there (the Atlantic) was at that time navigable; for in front of the mouth which you Greeks call, as you say, ‘the Pillars of Heracles’, there lay an island which was larger than Libya and Asia together; and it was possible for the travellers of that time to cross from it to the other islands, and from the islands to the whole of the continent over against them which encompasses that veritable ocean. For all that we have here, lying within the mouth of which we speak, is evidently a haven having a narrow entrance; but that yonder is a real ocean, and the land surrounding it may most rightly be called, in the fullest and truest sense, a continent. Now in this island of Atlantis there existed a confederation of kings, of great and marvellous power, which held sway over all the island, and over many other islands also and parts of the continent…” [6].

Now, before continuing, we must immediately answer the understandable perplexities raised by this passage: is it reasonable to suppose that the Atlantic Ocean was navigable in remote times? In reality, we have already tried to give a rational answer to this question in a previous article [7], the salient points of which we now report here. In it we first pointed out that the Greek historian Plutarch (c. AD 46-120) mentions a “great continent” [8] surrounding the Atlantic Ocean and the islands that lie on that route, and then focuses on an ancient settlement of Europeans, called “continental Greeks” [9], in the Canadian region of the Gulf of St. Lawrence [10], of which he indicates the latitude with astonishing precision. Cross-referencing these data with the results of a recent study on European megalithism, which argues “for the transfer of the megalithic concept over sea routes emanating from northwest France and for advanced maritime technology and seafaring in the megalithic Age” [11], it follows that this haven mentioned by Plato is identifiable with the Gulf of Morbihan—a natural harbor in southern Brittany, France—considered by scholars a focal point of the European Neolithic during the mid-5th millennium BC. This is exactly where, near its “narrow entrance”, as Plato claims, the remains are still found of an extraordinary alignment of nineteen gigantic menhirs. Here are the Pillars of Heracles.

All this, of course, proves the reliability of the picture outlined by Plato, also considering that the memory of ancient European settlements on the American side of the North Atlantic—perhaps also linked to the extraction of copper from the ancient mines of Isle Royale, the largest island in Lake Superior—emerges from various clues (which we also discussed in the article mentioned above), such as the persistence of myths and legends comparable to those of the Old World, as well as the Caucasian traits of some Native Americans, which seem to corroborate the idea of ancient contacts between the two opposite sides of the Atlantic.

On the other hand, there are scholars who have linked the myth of Atlantis to megalithism [12], traces of which are actually found almost all over the world, together with myths and legends that are often very similar to each other and that are are present in civilizations that are even very distant. The Holocene Climatic Optimum (HCO) greatly favored this hypothesized prehistoric globalization through navigation, which preceded by millennia that achieved by European fleets starting from the sixteenth century. In fact, until the third millennium BC, the HCO simultaneously made the current Sahara Desert green [13], and the Arctic Ocean navigable during the summer [14]. This favored direct communications between the Atlantic and the Pacific through a polar route, following an easy coastal navigation along the northern Canadian coast, thus avoiding having to cross the dangerous and very distant Strait of Magellan.

Let us now return to the islands on the Atlantic route referred to both by Plato, who explicitly names Atlantis among them, and by the passage in Plutarch mentioned above, which outlines an ancient route to the American continent via four intermediate islands, located at a high latitude in the North Atlantic. Plutarch first mentions the island of Ogygia, located “five days’ sail from Britain, towards the sunset”; then he mentions three other islands located beyond Ogygia, “as distant from each other as from it”, and immediately after the “great continent” that surrounds the “great sea” [15]. Here it is important to underline that these are islands located at a high latitude, since, as Plutarch points out, there in summer travellers “see the sun pass out of sight for less than an hour over a period of thirty days, and this is night, though it has a darkness that is slight and twilight glimmering from the west” [16].

Given that in a previous work we identified Ogygia with one of the Faroe Islands [17] (which are actually located in the direction of the sunset with respect to the northern tip of Scotland during the sailing season, that is around the summer solstice, when the sun, due to the high latitude of that archipelago, sets almost in the north), those three islands in the North Atlantic along the route to the American continent correspond to Iceland, Greenland and Newfoundland, which in fact, as Plutarch states, are closer to the coast of America than Ogygia is.

This photograph by Plutarch on the geographical reality of the islands that are located towards the northern tip of the Atlantic on the route to the American continent, appears truly extraordinary. Furthermore, its reliability is corroborated by another astonishing statement, when Plutarch immediately afterwards tells us of the presence, on the coast of the overseas continent, of “a gulf no less extensive than the Maeotis (today’s Sea of Azov, near Crimea), whose mouth is exactly in a straight line with the mouth of the Caspian Sea” [18]. According to Minas Tsikritsis [19], here the reference is to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, on the Atlantic coast of Canada: in fact, the latitude of its mouth, 47°, is actually the same as the “mouth of the Caspian Sea”, that is, the Volga delta. All this says a lot about the geographical knowledge of the ancients and their ability to navigate across the oceans [20].

Plato’s Atlantis and Greenland

Plutarch says that on one of those northern islands along the route to the American continent “Cronus according to the mythology of the barbarians is held prisoner by Zeus”, adding immediately after that this part of the ocean bears his name: “the Sea of Cronus” [21]. Let us compare this sentence with what Plato told us a little while ago: “For the ocean there (the Atlantic) was at that time navigable; for in front of the mouth which you Greeks call, as you say, ‘the Pillars of Heracles’, there lay an island which was larger than Libya and Asia together; and it was possible for the travellers of that time to cross from it to the other islands, and from the islands to the whole of the continent over against them which encompasses that veritable ocean”.

But is it possible to identify this vast island with a real island? And what does it mean that it was “larger than Libya and Asia together”? To understand the meaning of this sentence we must keep in mind that in the past the size of an island did not indicate its area at all (the measurement of which requires rather sophisticated techniques), but the length of its coast, which can be easily calculated, at least approximately, by sailing around it.

As an example, here is how Diodorus Siculus indicates the size of Britain (today’s Great Britain): “Of the sides of Britain the shortest, which extends along Europe, is seven thousand five hundred stades, the second, from the Strait to the (northern) tip, is fifteen thousand stades, and the last is twenty thousand stades, so that the entire circuit of the island amounts to forty-two thousand five hundred stades” [22]. Moreover, many centuries later Christopher Columbus also proceeded in the same way, as can be seen from his ‘Letter to Luis de Santángel’, where among other things he states that there was an island larger than England and Scotland together. In this regard, Luigi De Anna specifies that “when Columbus says that the island of Juana is ‘larger’ he means, being a sailor, to refer to the coastal perimeter and not to its surface” [23].

At this point, to understand the true meaning of the phrase “larger than Libya and Asia together” just take a look at the geographical map. To indicate the size of the island of Atlantis, Plato compares its perimeter with the coastal development of Libya, that is, of Northern Africa starting from Gibraltar, to which he adds that of the Palestinian coast, Lebanon, Syria and Anatolia up to the Dardanelles Strait.

This length, corresponding to the development of the entire southern side of the Mediterranean coast from Gibraltar to the Dardanelles, is greater than the perimeter of all the islands in the world, except Greenland, which, with its surface area of over 2 million sq km, is by far the largest island [24]. Indeed, Greenland’s deeply indented coastline is 24,430 miles (39,330 km) long [25], a distance roughly equivalent to Earth’s circumference at the Equator, far greater than the length of “Libya and Asia together”!

At this point Greenland, which is actually on the route to the American continent indicated by both Plato and Plutarch, is the only island on Earth that can be identified with Plato’s Atlantis, both for its position and its size.

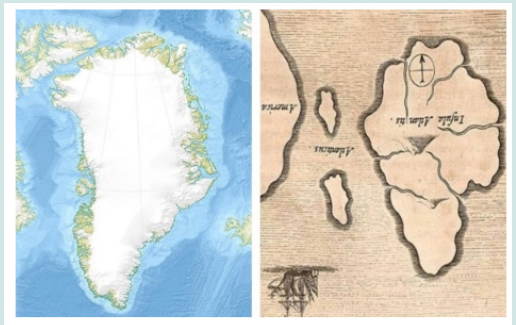

Another confirmation of this identification is found in its morphology. According to Plato, on the island of Atlantis there was a vast oblong central plain “surrounded by mountains that extended to the sea” [26] and indeed Greenland, under the ice cap that currently covers it, has a vast depression surrounded by mountain ranges (Figure 1).

This depression set between the mountains, which extends from north to south approximately between the 80th and 66th parallel, in its northern part is characterized by an enormous canyon (the “Grand Canyon of Greenland”), while below the 70th parallel it corresponds to that marvelous quadrangular plain, “which is said to have been the fairest of all plains” [27], the size of which Plato was keen to hand down to us: 3000x2000 stadia [28], corresponding approximately to 540x360 km.

Figure 1: Greenland in its geographical context (left) and beneath the ice sheet that currently covers much of it (right).

All this immediately explains the reason for the colossal system of canals that the Atlanteans had created both within the plain itself and along its perimeter, where they had built an enormous quadrangular trench, large enough to arouse Plato’s wonder:

“Now as a result of natural forces, together with the labors of many kings which extended over many ages, the condition of the plain was this. It was originally a quadrangle, rectilinear for the most part, and elongated; and what it lacked of this shape they made right by means of a trench dug round about it. Now, as regards the depth of this trench and its breadth and length, it seems incredible that it should be so large as the account states, considering that it was made by hand, and in addition to all the other operations, but none the less we must report what we heard: it was dug out to the depth of a plethrum and to a uniform breadth of a stade, and since it was dug round the whole plain its consequent length was 10,000 stades. It received the streams which came down from the mountains and after circling round the plain, and coming towards the city on this side and on that, it discharged them thereabouts into the sea” [29].

In fact, in that particular geographical situation, it was absolutely necessary to regulate the waters that, descending from the mountains towards the central depression of the island (especially in the thaw season), tended to periodically flood it.

But now it is time to focus on the capital city of the island, whose name Plato did not pass down to us, and on the strange circular structure of its port. However, first we should note a detail—the presence of a hot spring, which Plato mentions twice [30] on the hill in the center of the city—which fits well into the geographical framework outlined here. In fact, in Greenland, hot springs are a fairly common natural phenomenon [31].

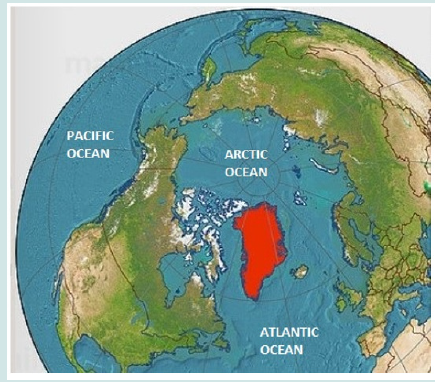

But where was this city located? Plato tells us at the beginning of the passage in which he tells us how the god of the sea built it: “Bordering on the sea and extending through the center of the whole island there was a plain, which is said to have been the fairest of all plains and highly fertile” [32]. Now, here you only have to take a look at the map of Greenland (Figure 1) to see that, while its eastern coast is completely lined with mountain ranges, on the western coast, level with Disko Bay (around the 70th parallel), the sea laps the plain for a stretch. Not only that: just as Plato states, Disko Bay is right in the centre of the western coast of the island (Figure 2).

This confirms what we are trying to demonstrate, that is, that Plato, or rather, his source, did not invent anything, but said true things with absolute knowledge of the facts (let’s also think about the three consecutive adverbs with which he declares himself absolutely certain of the existence of the continent beyond the ocean). Therefore, also considering its enormous dimensions, his Atlantis can only correspond to Greenland.

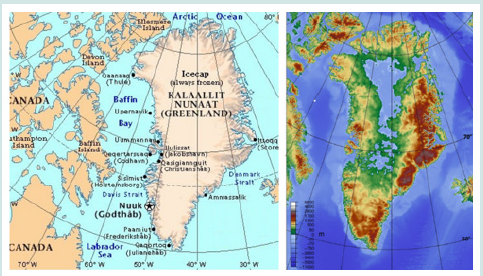

In further support of the hypothesis that the capital of Atlantis was located in the area of Disko Bay (which corresponds to the most important of the ancient settlements of Greenland, which even now enjoys a better climate on the western side), we note that there is a map of southern Greenland, made in 1747 by Emanuel Bowen, in which a very long channel is drawn that starts from the eastern coast, level with Iceland, and connects it with the western coast, flowing out right where Disko Bay opens up (Figure 3).

Figure 2: An image of Disko Bay, with the island of the same name, and (on the right) its location exactly in the Centre of the west coast of Greenland, right where the central plain reaches the sea, as Plato states.

Figure 3: Detail of Bowen’s map compared with the map of the southern Greenland soil currently under ice.

On this channel, Bowen’s map bears a revealing inscription: “It is said that these straights were formerly passable, but now they are shut up with ice”. Most likely the reference is to the “medieval warm period”, when the polar ice pack was significantly reduced within the Arctic Sea and floating ice became very rare both around Iceland—which then became a flourishing land—and in front of Greenland.

The latter, which is now largely covered by ice, was called “Green Land” around the year 1000 AD, when it was colonized by the Norwegian Vikings, due to the large extension of meadows that they found there upon their arrival. “Interpretation of ice-core and clam-shell data suggests that between AD 800 and 1300 the regions around the fjords of southern Greenland had a relatively mild climate, several degrees Celsius warmer than usual in the North Atlantic” [33], with trees and herbaceous plants growing and livestock being farmed. Barley was grown as a crop up to the 70th parallel [34].

Furthermore, as Prof. Franco Ortolani points out, at that time “paleo temperatures show a marked increase in the average temperature that allowed the cultivation of vineyards in Norway” [35]. At that time the vine also grew in England: “England was a leader in grape growing and winemaking through much of the Middle Ages. At the end of the 11th century there were perhaps 50 vineyards in the southern half of the country—most associated with the church—that produced wine. These vineyards prospered for more than 300 years, making England an important center of European winemaking” [36]. More generally speaking, “Change— large, rapid, and global—is more characteristic of the Earth’s climate than is stasis” [37].

Bowen’s map proves the possibility that in warm periods the ice sheet that envelops Greenland is significantly reduced, indeed, at least in the southern part of the island it retreats until it disappears completely. Now, in the medieval warm period such a significant effect was caused by an increase in temperatures that nevertheless remained somewhat below what had occurred millennia before, during the Holocene Climatic Optimum (HCO) [38]. To this we must add that the latter lasted much longer, for several millennia, with consequences on the thawing of the ice sheet that were certainly much greater.

It can be deduced that during the HCO, chronologically superimposable to the Neolithic period and the early Bronze Age, a conspicuous part of the Greenland territory must have remained free from ice, allowing the Atlantic civilization to develop, prosper and expand throughout the world, taking advantage of its extraordinary geographical position among the Arctic Ocean, the Atlantic and the Pacific.

Bowen’s map also tells us something else: in fact, already at first sight the almost rectilinear aspect of that channel—which started from a fjord on the south-eastern coast, almost opposite the NW tip of Iceland, and reached Disko Bay on the western one, for a length of over 600 km—could correspond to the northern side of the enormous quadrangular trench that, according to Critias, had been dug by the Atlanteans around the central plain of the island and intersected the outermost circular channel of the port of the capital of Atlantis. Indeed, that trench “received the streams which came down from the mountains and after circling round the plain, and coming towards the city on this side and on that, it discharged them thereabouts into the sea” [39].

Therefore, we have confirmation that the capital of the island, according to what the Critias and this map suggest, was most likely located at the intersection between the northern and western sides of the trench that surrounded the central plain, and precisely in the area of Disko Bay, on the western coast of the island, facing Baffin Island and the American continent, also considering the fact that the western side of Greenland enjoys a better climate than the eastern one.

In fact, it is no coincidence that most of the finds from that period, attributable to the oldest archaeological culture currently known in southern Greenland, the Saqqaq (2500-800 BC) were found near Disko Bay, including the site of Saqqaq, from which that culture takes its name [40]. Incidentally, it seems rather curious, and worthy of in-depth investigation, that the name Disko Bay corresponds to the Greek word “diskos” and the Latin “discus”, “disk”, which immediately recalls the look of the extraordinary circular port of Atlantis, described in detail by Plato and which we will focus on shortly.

Returning to the channel in Bowen’s map, it must have been very important for the ancient navigators heading to Atlantis, coming from the European coasts and the central Atlantic, who, after having made their last stop in Iceland (corresponding to ancient Thule), could directly reach the capital located on the western coast of Greenland through it, significantly shortening the route and without having to be forced to double the southern end of the island in a very treacherous sea.

As for the location of Thule, some writers of late classical times or the early Middle Ages, such as Orosius, Solinus and the Irish monk Dicuil placed it to the north and west of the British Isles, thus strongly suggesting that it was Iceland. This location, supported by Adam of Bremen: “Thule is now called Iceland, because of the ice that covers the ocean” [41], in our opinion is the most reliable.

Here we hypothesize that this name, “Thule”, could be traced back to the Proto-Indo-European root, *dhwer-, which means “door” (from which the Greek thura, the German Tür, the English door, the ancient Nordic dyrr and the Sanskrit duárah), presumably meaning “the entrance, the door” to Greenland (a bit like the name of the Florida Keys archipelago recalls that it is located in front of Florida). In fact, after the crossing of the Atlantic, for navigators coming from Europe Iceland represented the “door” to Greenland, from which it is separated by a stretch of sea, less than two hundred miles long (which at that latitude during the summer season enjoys uninterrupted light).

Opposite Thule, today’s Iceland, there was the mountainous eastern coast of Atlantis. In particular, in the Watkins Ridge, a large mountain range located on this side (it is the first image of the Greenland coast that appears on the horizon to sailors coming from Iceland), stand the three highest peaks of Greenland: Gunnbjørns Fjeld (3,694 m), Dome and Cone (Figure 4).

They remind us of a phrase from Critias (referring to the mountains that surrounded the central plain): “And the mountains which surrounded it were at that time celebrated as surpassing all that now exist in number, magnitude and beauty” [42].

Incidentally, we note that these three peaks are contiguous and almost aligned, with an arrangement that closely resembles that of the three pyramids of Giza. Here we should perhaps ask ourselves whether, as Robert Bauval proposed for the three pyramids, the Atlanteans did not associate these three great mountains with the stars of Orion’s Belt, considering how important and universally widespread the correspondence between heaven and earth was among ancient cultures. “As above, so below” is the famous formula traditionally attributed to Hermes Trismegistus. At this point one might even suppose that it was precisely the memory of these Greenland mountains that inspired the construction of the three pyramids in the valley of Giza [43].

As for the port of the capital, it consisted of three concentric circular canals, alternating with two circles of land, which surrounded a central island, five stadia wide (about 900 m), on which the royal palace stood:

“For, beginning at the sea, they bored a channel right through to the outermost circle, which was three plethra in breadth, one hundred feet in depth, and fifty stades in length; and thus they made the entrance to it from the sea like that to a harbor by opening out a mouth large enough for the greatest ships to sail through. Moreover, through the circles of land, which divided those of sea, over against the bridges they opened out a channel leading from circle to circle, large enough to give passage to a single trireme; and this they roofed over above so that the sea-way was subterranean; for the lips of the landcircles were raised a sufficient height above the level of the sea. The greatest of the circles into which a boring was made for the sea was three stades in breadth, and the circle of land next to it was of equal breadth; and of the second pair of circles that of water was two stades in breadth and that of dry land equal again to the preceding one of water; and the circle which ran round the central island itself was of a stade’s breadth. And this island, wherein stood the royal palace, was of five stades in diameter” [44].

Still on this port with such a particular circular look, Enrico Turolla, immediately after having declared his belief that Plato “is the bearer of a voice that comes from further away”, wonders whether “the coincidence with the structure of prehistoric Mexican cities is a coincidence (...) The island with a mountain surrounded by concentric rings of walls and canals is also depicted in the Aztec drawings of Aztlán, the homeland of the Aztecs. Where the consonance Aztlán with Atlas is notable”.

Furthermore, Norse mythology suggests a direct connection between Greenland and the Aztec world, a well-known characteristic of which was the torture of the heart torn from the victim’s chest. In fact, in the Greenlandic poem of Atli, ‘Atlakvidha in Groenlenzka’, Hogni is tortured in this very way. The Greenlandic dimension of Atli also appears in another poem of the Edda: ‘Atlamál in Groenlenzko’.

Still on Atli, it gives food for thought that his name recalls Atlas, the first king of Atlantis, who gave his name to the island (and to the Atlantic Ocean).

We also note another significant example of a circular port, that of Carthage, the city of Phoenician origin that gave so many headaches to the ancient Romans. It too recalls the concentric circles that Plato attributes to the capital of the Atlanteans. Furthermore, Carthage is the homeland of the mysterious character to whom Plutarch attributes the news about the overseas continent and the islands of the northern Atlantic that were along the route to reach it, first dwelling on the island where “Cronus is confined by Zeus, and the ancient Briareus, holding watch and ward over those islands and the sea that they call the Cronian Sea, has been settled close beside him”, and then adding that Cronus in Carthage “enjoys great honors” [45]. In short, the ancestors of the Phoenicians, ancient navigators whose origins are unknown, were probably linked to the Atlantic world.

Mineral Resources

Another important point of contact between Plato’s Atlantis and Greenland is the great wealth of mineral resources. As for the former, Plato states that “The island furnished most of the requirements of daily life, metals, to begin with, both the hard kind and the fusible kind, which are extracted by mining” [46].

As for Greenland, “The Center for Minerals and Materials (MiMa) at GEUS has just published a report which assesses the potential for critical raw materials in Greenland (…) The report shows that Greenland has a large untapped potential for critical raw materials—including the rare earth metals graphite, niobium, platinum group metals, molybdenum, tantalum and titanium, all of which already are or will become important for the green transition” [47].

More generally speaking, “‘During the Cold War, the Arctic was cold in all its guises; literally and also politically, it was a place apart’, says Caroline Kennedy-Pipe, head of politics and international studies at the University of Loughborough. Since the 1990s, as the Cold War melted away, so has Arctic melting accelerated. ‘What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. Just as melting Arctic glaciers lead to sea-level rise in the eastern Mediterranean, so are the emerging geopolitics of the Arctic impacting how the world’s major powers interact with one another’ (…) In Greenland, melting ice is exposing mineral belts that are highly likely to contain gold, nickel, platinum-group elements, copper, lead, zinc, molybdenum, diamonds and rare earth elements” [48].

Let us return to Plato, who, after having declared that among the resources of Atlantis there were all kinds of metals which are extracted by mining, points out that there was “also that kind which is now known only by name but was more than a name then, there being mines of it in many places of the island, I mean ‘orichalcum’, which was the most precious of the metals then known, except gold” [49].

This passage tells us that orichalcum was certainly a precious metal (and not an alloy of copper and zinc, as it is often usually considered today) and this is also evident from another passage in which it is mentioned in Greek literature. In the 2nd Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite’, the earrings on the statue of the goddess are of “precious orichalcum and gold flowers”. This confirms beyond any doubt that it was a noble metal, comparable in value to gold, as Plato claims. Furthermore, as we will see shortly, in the Critias it is mentioned, together with gold and silver, among the metals that decorated the sumptuous temple of Poseidon.

But what was orichalcum? In order to identify it, we must keep in mind that in the ancient classical world, gold and silver were the only precious metals known. On the other hand, platinum (whose main deposits are found in the Ural Mountains, Alaska and South America) remained unknown in Europe until Antonio De Ulloa discovered it in 1735 in Colombian deposits, although some pre- Columbian populations knew this metal and worked it. Since orichalcum is not an alloy but a true metal, and all existing metals are included in Mendeleev’s periodic table of elements, it follows that it is identifiable with platinum. Indeed, platinum is still today, as it was then, the most precious metal together with gold, also because of its scarcity in Earth’s crust.

As for the Platinum Group Element (PGE) resources in Greenland, they “attracted interest already in the 1960s and have been part of Greenland exploration since the 1970s” [50] (Figure 5) [51].

At this point, the fact that even such a rare metal is found in Greenland is a further indication that the latter is identifiable with the island Atlantis. It should also be noted that the assessments of the presence of raw materials in the Greenland subsoil are based on surveys limited to places (usually near the coasts) where there is no ice cover now. In short, as Global Warming in the coming years will increase the surface free from ice, there could be new positive surprises.

Furthermore, it gives food for thought that, as Plato states, at the time of the flowering of Atlantis the value of orichalcum was comparable to that of gold, just as it is now. In fact, currently “Platinum tends to out-perform gold during prolonged periods of economic growth or perceived monetary stability and to underperform gold during prolonged periods when confidence in the economy and the financial system is deteriorating” [52].

This seems to suggest that the commercial dynamics of the prehistoric civilization described by Plato, presumably based on trade even over long distances, despite the millennia that separate it from us, were perhaps, at least in some ways, not too different from those of today. In this regard, here is an exciting, lively, visual and sound “spot”, almost a television news image that, thanks to Plato, comes to us directly from the Atlanteans’ world, allowing us for a moment to open up like a tear in the wall that prevents us from seeing the daily life of the men of that time: “…The sea-way and the largest harbor were filled with ships and merchants coming from all quarters, which by reason of their multitude caused clamor and tumult of every kind and an unceasing din night and day” [53].

The Tragic End of Atlantis

All this set of correspondences—size, geographical position, morphology, large mineral resources—confirms that Atlantis is identifiable with Greenland, obviously in an era in which the Arctic Ocean was navigable.

At this point, however, an objection arises spontaneously. It is commonly believed that the island of Atlantis was suddenly swallowed up by the sea and therefore, contrary to what we have just seen, its remains should lie somewhere on the ocean floor. We must therefore examine the question in depth, rereading the passages of Plato’s two dialogues that deal with the end of the island to clarify this contradiction.

Indeed, here the two dialogues diverge. The Critias dialogue— from which we have drawn most of the information reported above, and in particular that relating to the great mountains that surrounded the central plain, which are absolutely incompatible with the sudden disappearance of the island—stops abruptly just before Zeus announces in the assembly of the gods what kind of punishment he would inflict on the Atlanteans for their growing, intolerable iniquity.

Instead, the Timaeus relates that “At a later time there occurred portentous earthquakes and floods, and one grievous day and night befell them, when the whole body of your warriors was swallowed up by the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner was swallowed up by the sea and vanished; wherefore also the ocean at that spot has now become impassable and unsearchable, being blocked up by the shoal mud which the island created as it settled down” [54]. It is evident that there is no trace of mountains here.

All this suggests that the myth of Atlantis was born from the superposition of two very different geographical realities: one, told in the Critias, corresponds to a very large island on whose coasts many very high mountains rise (which clearly cannot sink and disappear), while the other, that of the Timaeus, seems at least in part to refer to a flat island that in the end, due to a cataclysm, is swallowed up by the sea.

What appears to be the oldest of the two layers, described in great detail in the Critias, as we have just had the opportunity to verify, for many good reasons undoubtedly corresponds to Greenland, as does the part of the narrative of the Timaeus that we examined first, which refers to the route to the American continent and the intervening islands and underlines the enormous size of the island, “which was larger than Libya and Asia together”. But what can be said about the other part, the one relating to the war of the Atlanteans with Athens and their catastrophic end following a terrifying tsunami?

In this regard, there is a particular geographical reality, which thousands of years ago was actually “swallowed up by the sea and vanished”, to which one can associate some reason for identifying it with that low island, suddenly disappeared, mentioned in the Timaeus. We are referring to Dogger Bank, a large sandbank in a shallow area of the North Sea about 100 kilometres off the east coast of England, which extends over about 17,600 sq km [55] (Figure 6).

In the Mesolithic period it was still an emerged land, called by modern scholars the Island of Doggerland, which was located between England and Denmark, off the Dutch coast. It was what remained of a vast territory that in an even earlier era extended from England to the Jutland peninsula (i.e. over a large part of the current North Sea)—the existence of which had already been hypothesized by Otto Rydbeck [56] at the beginning of the last century—which gradually sank under water as the progressive melting of the ice after the end of the last glaciation raised the sea level.

Doggerland was a low land, without mountains, with lagoons, salt marshes, beaches, rivers, swamps and lakes, where traces of human activity have been found (including a 22 cm long bone harpoon), as well as remains of animals, such as lions and mammoths [57]. But it seems that the definitive disappearance of Doggerland was preceded by a sudden catastrophic event. Around 6200 BC the island may have been submerged by a terrifying tsunami, caused by an enormous underwater landslide, the Storegga Slide, which occurred in the Atlantic, off the coast of Norway. It has been hypothesized that coastal areas of both Britain and mainland Europe, extending over areas which are now submerged, would have been temporarily inundated by a tsunami triggered by the Storegga Slide. This event would have had a catastrophic impact on the Mesolithic population at the time [58]. It is estimated that up to a quarter of the Mesolithic population of Britain lost their lives [59]. However, the issue is controversial [60].

It can be assumed that after the disaster, which erased every trace of life on Doggerland, what remained of it continued to sink over time into the sea, whose level rose more and more, until its definitive disappearance; however, those sediments and muddy seabeds mentioned in the Timaeus remained on the surface for a long time, hindering navigation.

It is, therefore, not unreasonable to suppose that the memory of the tragic disappearance of the flat island of Doggerland (that it was an outpost of the Atlanteans on European territory?) over time was superimposed on that, certainly due to the frost, of the other island, Greenland, much larger and geologically completely different, as appears from the very accurate description given in the Critias.

Regarding that Athens with which the Atlanteans were engaged in a war shortly before the tsunami, Plato himself states that it was a city with a very different appearance from the current one. Indeed, this prehistoric Athens, founded and led by the goddess Athena and Hephaestus, was located in a territory completely different from that of Greek Athens: “But at that epoch the country was unimpaired, and for its mountains it had high arable hills, and in place of the ‘moorlands’, as they are now called, it contained plains full of rich soil; and it had much forestland in its mountains (…) The acropolis, as it existed then, was different from what it is now (…) But in its former extent, at an earlier period, it went down towards the Eridanus and the Ilissus, and embraced within it the Pnyx; and had the Lycabettus as its boundary over against the Pnyx” [61].

We note that the breadth attributed to this city by Plato corresponds to the adjective “broad” with which Homer defines Athens [62], a city that, according to our previous research (according to which the Homeric poems would have originated from sagas born in northern Europe before the descent of the Achaeans into the Mediterranean) [63] would be located in the territory of the current Swedish city of Karlskrona, overlooking the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, therefore not very far from the North Sea where the Dogger Bank is located. Incidentally, this also explains the strangeness of the plural name of Athens, a form that refers to the location of its Baltic counterpart, which extended over the mainland and the adjacent islands [64].

As for the end of the civilization of the Greenlandic Atlanteans, on which Critias is silent because it was interrupted just when Zeus was about to announce it—unless the interruption was wanted by Plato himself, who perhaps could not explain the divergence from the end of the Atlanteans of Doggerland, who fought against the Athenians and were then overwhelmed by the tsunami—perhaps we find the last memory of it in the Iranian world. According to the story of the Avesta (the complex of sacred books of Zoroastrianism), the god Ahura Mazda announced to Yima, the mythical first king of men, that a series of very harsh winters would destroy his country and that, after that, there would be ten months of winter and two of summer [65]. This is the current climate of the Arctic regions. It is also interesting to note that the name Yima is related to the concept of “twins”, typical of the kings of Atlantis [66]. In fact, in the Hindu world Yima becomes Yama (or Yamarāja), God of death and the underworld, twin of Yami [67].

Moreover, the memory of an ancient climatic disaster has remained vividly preserved in the memory of many peoples. Let us think for example of the terrible Ragnarok of the Nordic myths, the so-called ‘Twilight of the Gods’: “A terrible and frightening winter named Fimbulvetr will announce it; from every side the snow will fall whirling, the cold will be intense and the winds biting. The sun will no longer be enjoyed. Three winters will follow one another and there will be no summers in between” [68].

Another example is found in the Arthurian myths, of Celtic origin, where the ‘Wasteland’ is spoken of, “the ‘desolate land’, abandoned by its inhabitants, devoid of cultivation, immersed in an early winter” [69], to which perhaps the prophet Isaiah also alludes: “Behold, the Lord depopulates the earth, devastates it, alters its aspect, disperses its inhabitants” [70].

In any case, the arrival of the frost and the dramatic conclusion of an era are well suited to the tragic end of Atlantic civilization in Greenland, of which the interruption of the Critias at the very culminating moment has unfortunately deprived us of direct testimony.

The White Island and the Thigh Constellation

Now we will examine a text very far from the world of classical Greece. It is a passage taken from the Shanti Parva, which is the longest book of the Mahabharata, the great Indian poem:

“On the northern shores of the Ocean of Milk there is an island of great splendour called by the name of White Island. The men that inhabit that island have complexions as white as the rays of the Moon and are devoted to Narayana. Worshippers of that foremost of all Beings, they are devoted to Him with their whole souls (…) Indeed, the denizens of White Island believe and worship only one God (…) Eagerly desirous of beholding Him and our hearts full of Him, we arrived at last at that large island called White Island” [71].

Now, also considering that “The men that inhabit that island have complexions as white as the rays of the Moon”, the Ocean of Milk seems to be the North Atlantic, which often, due to cloud cover and haze, often appears white or gray [72], very different from the Indian Ocean.

As for the name ‘White Island’, it seems to us so appropriate that it represents in itself important evidence in favour of its identification with Greenland: in fact, those who arrived from Iceland when approaching the coast of Atlantis first saw the very high mountains of the Watkins Ridge looming on the horizon, which then as now were perpetually covered with snow and ice.

In short, this citation of the White Island in the Indian Mahabharata has all the air of being an ancient memory of Plato’s Atlantis, and being found in an ancient text very distant from both the classical world and the Egyptian culture from which Plato claims to have drawn his story, it represents another precious testimony in favor of the real existence of that civilization and its location on the “great island”, as that poem defines it, in the North Atlantic.

But this passage is also very significant for another reason. The god of the White Island, Narayana, “floated on the snake Ananta (“Endless”) on the primeval waters” [73]. Narayana is, therefore, the equivalent of the god of Atlantis, Poseidon, lord of the sea as well as father of Atlas and founder of the royal lineage that reigned over the island. And it is to Poseidon that the Atlanteans dedicated the sumptuous temple that Plato describes in detail: “And the temple of Poseidon was a stade in length, three plethra in breadth, and of a height which appeared symmetrical therewith; and there was something of the barbaric in its appearance. All the exterior of the temple they coated with silver, save only the pinnacles, and these they coated with gold. As to the interior, they made the roof all of ivory in appearance, variegated with gold and silver and orichalcum, and all the rest of the walls and pillars and floors they covered with orichalcum. And they placed therein golden statues, one being that of the God standing on a chariot and driving six winged steeds, his own figure so tall as to touch the ridge of the roof, and round about him a hundred Nereids on dolphins” [74].

On the other hand, the evident relationship (which seems to presuppose a primordial identity) between the figures of Poseidon and Narayana is undoubtedly enriched by the relationship that we had previously found between the Greenlandic Atli—who in Nordic mythology is subjected to a torture typical of the Aztec world (but Turolla had already warned us of the analogy between the singular circular port of Atlantis and the mythical Aztlàn)—and the name of Atlas.

In short, the myth of Atlantis is revealing an increasingly “international” dimension, which perhaps is not possessed to the same extent by any other myth in the world. Indeed, we find Greece, Egypt, India, Norse mythology, even the Aztecs involved! But this on the other hand appears consistent with the global, as well as very ancient, dimension that Plato attributes to the lost island, whose kings were the lords of the seas.

Furthermore, Narayana gives us another cue. From his thigh was born Urvashi, a beautiful celestial nymph, whose name could in fact derive from ūru [75], “thigh” in Sanskrit. This has a significant parallel in Greek mythology, where the god Dionysus was born from the thigh of Zeus, who saved him by placing him in his “thigh” after killing his mother, Semele, with a thunderbolt, who was still carrying him in her womb.

As for Dionysus, born from the thigh of Zeus, and another god of wine, Liber, who is his counterpart in ancient Roman religion, Pliny explicitly mentions their relationship with the “thigh” (“meros” in Greek): “Many attribute the city of Nisa and Mount Meru, sacred to the Father Liber, to India, from which comes the legend that makes him born from the thigh of Jupiter” [76]. But what does “being born from the thigh” mean?

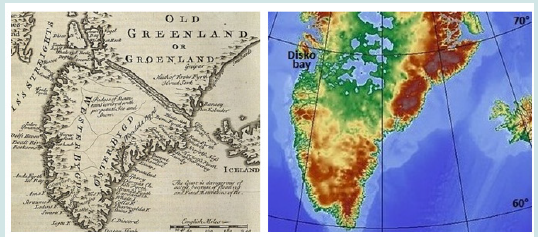

Here the comparison with the profile of Atlantis in the map by Athanasius Kircher (a German Jesuit of the 17th century) comes naturally, showing an enormous island, located in the Atlantic, with a vaguely ovoid profile with the tip pointing south, which presents a remarkable similarity to that of Greenland (Figure 7). Incidentally, in Kircher’s map the north is indicated downwards; therefore, to compare it with Greenland it is best to overturn the map so as to bring the north upwards.

Here the analogy between the appearance of Greenland and the shape of Atlantis reported by Kircher is evident, similar to a gigantic thigh with the attachment to the hip to the north and the knee to the south. However, Kircher, evidently misled by the traditional erroneous identification of the Pillars of Hercules with the Strait of Gibraltar, thought it necessary to place Atlantis in front of the latter, which obviously made this map (whose origin is unknown) lose credibility. Incidentally, in Kircher’s map two other islands are indicated between Atlantis and the American continent, one of which, the larger, could correspond to the Canadian island of Baffin, while the other, smaller and located further north, could represent the last memory of Ellesmere.

At this point we also note that Meropeis is the name of a mythical island mentioned by the Greek writer Theopompus of Chios and preserved in the fragments reported in the ‘Varia Historia’ by Claudius Aelian, who places it beyond the Atlantic Ocean. For this reason, but also for the large dimensions attributed to it, it has often been identified with Plato’s Atlantis. Furthermore, we find a Merops king of Cos, called “the city of the Meropes” [77]. To this network of correlations, so intricate as to make it unlikely that they are all due to pure chance, we could also add that the name of Cos, the city of the Meropes, in turn is almost identical to the Latin word “coxa”, “thigh”.

On the other hand, “the Egyptians (…) called our Big Dipper Khepesh, “the thig” or “the ox-leg” [78]. In fact, the shape of the Bear, consisting of a tapered quadrangle followed by three other stars, suggests a thigh that continues with a slightly bent leg. This may suggest that—based on the old saying that “what is below is equal to what is above”, which in turn could recall more ancient roots [79]— the Atlanteans considered their thigh-shaped island, very close to the North Pole, as the projection on Earth of the Big Dipper, which is actually close to the North Celestial Pole. Therefore, the Earthly Thigh, i.e. Greenland, was probably considered the correspondent of the Celestial Thigh.

In short, just as France is called “the Hexagon” because of its shape and Italy is “the Boot”, in the same way the island of Atlantis was perhaps “the Thigh”. Thus we can begin to read in a new light the symbolism hidden behind the bizarre episode, narrated by Iamblichus, of Pythagoras showing a “golden thigh” to Abaris the Hyperborean, as well as the image of Christ in the Revelation of John, where very ancient concepts often echo, “On his robe and on his thigh he has a name written, King of kings and Lord of lords” [80]. So, one can suppose that in the ancient world the “Thigh” at least in certain traditional circles continued to be the very symbol of royal power, also considering that the sacred value connected to the “thigh” also appears in the Bible, where in uttering a solemn oath it was necessary to keep a hand under the thigh of the person to whom it was addressed: “And Abraham said unto his eldest servant of his house, that ruled over all that he had, Put, I pray thee, thy hand under my thigh” [81].

The Seafaring Dimension of Atlantis and its Strategic Position

Based on this interpretation of the image of the thigh, it is also worth reflecting on the bizarre sentence that Saxo Grammaticus, a medieval Danish historian (c. 1150-1220), has Amleth, the character who inspired Shakespeare’s Hamlet, utter: “As he passed along the beach, his companions found the rudder of a ship which had been wrecked, and said they had discovered a huge knife. ‘This’, he said ‘was the right thing to carve such a huge ham’; by which he really meant the sea, to whose infinitude, he thought, this enormous rudder matched” [82].

Here Saxo, or rather his Amleth, offers us a complex allegory of images, among which the apparent oddity of that “huge ham” stands out, which together seem to evoke an idea of past grandeur and power in a maritime context, over which however looms the disturbing perception of an ancient shipwreck. They are all aspects of a discourse that perfectly fits the grand, tragic dimension of the lost island. Going into more detail, we can try to isolate four distinct metaphors: the enormous rudder of the wrecked ship, the huge knife, the huge ham, the infinitude of the sea. It is a coded language expressed with symbolic images, behind which we can glimpse the main aspects of the myth of Atlantis in the story of the Critias: the dominion over the seas, the military power, the vastness of the island, its tragic destiny. That “huge ham” plastically represents the image of Atlantis, the Thigh Island as the projection on earth of the Big Dipper, which reflects its shape and position in the sky.

In any case, Hamlet’s words bring us back to the maritime vocation of the Atlanteans, lords of navigation, favored, as we have already said, by the Holocene Climatic Optimum, which, during the megalithic age, allowed ships to transit between the Atlantic and the Pacific directly through the Arctic Sea, which was free of ice and navigable during the summer. Indeed, the strategic position of the island in the North Atlantic context (Figure 8) immediately solves the enigma of the worldwide diffusion of myths, legends and artifacts common to peoples even very distant from each other.

In fact, Atlantis, in addition to being, as Plato says, in front of the European coasts and adjacent to the American continent, also overlooked the Arctic Sea, from which at that time with easy coastal navigation ships were able to easily reach the Bering Strait, from where they flowed into the Pacific Ocean. There they then skirted the coast of Alaska for a stretch until they found the north-east trade wind, which pushed their ships towards Polynesia, where the first islands they encountered were Hawaii (it is here, in the Island Hawaii, that in a previous article we located the mythical Elysian Fields, called the Rush Fields by the ancient Egyptians) [83].

In this regard, it should be noted that impressive megalithic remains are scattered throughout the Polynesian islands, often surprising not only for their size but also for their analogies with similar monuments found everywhere around the world. Think for example of the enormous constructions, made with large blocks of basalt, of Nan Madol in the Caroline Islands, where the archaeological area extends for 18 sq km on a hundred or so artificial islands connected to each other by a dense network of canals. But, in addition to the famous moai of Easter Island, among the most striking monuments is the imposing trilithon of Tonga, which has even been compared to Stonehenge.

Very surprising is the account of one of the first encounters between Europeans and Polynesians, which took place in 1595 in one of the Marquesas Islands, when “about four hundred Indians appeared, with almost white skin and of good stature, tall, robust and strong (…) Many of them are blond” [84]. We have confirmation of these Caucasian characteristics of some Polynesian natives in the notes of the Frenchman Louis-Antoine de Bougainville when he landed in Tahiti in 1768: “Men six feet tall and even more. I have never met men so well made and proportioned (…) Nothing distinguishes their features from those of Europeans” [85]. This is in line with the fact that, “among the Marquesans, 7.2% of men and 9.5% of women were found to have blue eyes” [86].

To the megalithic remains and the features of the people are added myths, stories, customs and social structures: in Polynesia we find the myths of the Flood and the Tower of Babel [87], but also striking is the name of the Ari’i (Ali’i in some dialects), the nobles, considered descendants of the Polynesian gods. But also the kavu, the “priest”—called Kahuna in the Hawaiian Islands—is almost homonymous with the koes (kaves in the Lydian language), the Greek priest of the Kabiric rites (a name also comparable to the Hebrew cohen and the Norse godhi). A special case is then that of the extraordinary similarity, noted by Guillaume de Hevesy [88], between the ‘rongorongo’ writing characters of Easter Island and those of the ancient civilization of the Indus Valley, located exactly at the antipodes.

More generally, from all this one can deduce that the Atlantic coasts of Europe were directly connected to those of Polynesia, Australia, the Far East and the western side of the Americas, through a polar route that hinged on Greenland (by this route the Bering Strait, that is, the gateway to the Pacific, is about as far from Scotland as the Caribbean is from Spain, but a good part of the route here is along the coast). This was also Columbus’ dream, which in a few years will be possible again, following the current global warming. Therefore, the position of the island Atlantis at the northern end of the Atlantic Ocean immediately gives an account of the correspondences between the civilizations of the Old and New Worlds and in particular of the worldwide diffusion of both megalithic structures and mythical tales common to peoples even very distant from each other.

As for Greenland today, here is a lucid analysis by William Tan: “Located in the Arctic Circle, Greenland (…) is strategically positioned on the shortest routes connecting Asia, Europe, and North America (…) The effects of global warming have thawed Arctic glaciers, thereby increasing the island’s habitable surface area and unlocking new natural resources such as oil and minerals (…) Global powers such as the United States, China, and Russia are racing to extend military and economic influence in the region as it becomes more habitable (…) Controlling Greenland offers military, economic, and political advantages for these three superpowers looking to monitor their global opponents. Between military outposts, technological developments, and mining infrastructure, the possibility of securing the optimal geographic foothold transformed Greenland from a barren land of ice into a geopolitical hotspot (...) Climate change opened access to untapped oil and natural gas reserves and new shipping routes among Asia, Europe, and the United States. Since the Arctic contains 13 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil and 30 percent of its undiscovered natural gas, controlling Greenland facilitates access to these natural resources (…) The invasion of Ukraine proves that global powers will go to war over vital regions, precariously positioning Greenland as the next prime hotspot for future conflict as rival countries quietly build up their influence across the island” [89].

In this situation, it is of great importance to know the speed of the melting of the island’s ice cap. According to a study recently published in Nature Geoscience, entitled “Increased crevassing across accelerating Greenland Ice Sheet margins”, between 2016 and 2021 “Large and significant increases in crevasse volume occurred at marine-terminating sectors with accelerating flow (…) Changes in crevasse volume correlate strongly with antecedent discharge changes, indicating that the acceleration of ice flow in Greenland forces significant increases in crevassing on a timescale of less than five years. This response provides a mechanism for mass-loss-promoting feedbacks on sub-decadal timescales, including increased calving, faster flow and accelerated water transfer to the bed” [90].

If in the near future the melting of the southern part of the Greenland ice cap confirms the existence of the channel that thousands of years ago connected Disko Bay to the eastern coast of the island, level with Iceland, the extraordinary strategic and commercial value of this ancient maritime hub will appear even clearer, located at the center of a global network of ocean transport that from the Atlantic coasts of America, Europe and Africa, passing through the Canadian and Siberian ones, extended—and will soon extend again—towards the entire Pacific Ocean, as far as Asia and Oceania.

Conclusion

In this article we have verified that there are many valid reasons to consider the comparison between Plato’s Atlantis and Greenland plausible, such as their position, their enormous size—Atlantis was “larger than Libya and Asia together”, while Greenland’s coastline is almost equivalent to Earth’s circumference—their peculiar morphology, their thigh-shaped appearance, their great mineral resources (including platinum, a very rare metal in the Earth’s crust) to which must be added the astonishing precision of Plato’s and Plutarch’s geographical indications regarding the islands along the northern Atlantic route to the American continent (of whose real existence Plato is keen to declare he is absolutely certain).

But let us also think of other very precise geographical details, such as the correspondence between the point where the plain of Atlantis approaches the sea—which Plato correctly places level with the centre of the island—and Disko Bay on the western side of Greenland, or even the fact that with this key the meaning of the name of the White Island “on the northern shores of the Ocean of Milk” mentioned in the Mahabharata is immediately clarified.

In any case, the great distance that separates the cultures involved in this study attests to the antiquity of these conceptions, supporting the idea that there was a global prehistoric civilization spread across the planet, of which Plato left us the last memory by passing down to us the myth of Atlantis, of which what has emerged here represents further confirmation. This implies that in prehistory there was a civilization with adequate knowledge of the art of navigation, as confirmed by recent studies on megalithism. However, these themes require further studies and insights, which in the future may shed new light on the prehistory of humanity.

More generally, from this identification of the mythical Atlantis with present-day Greenland, recently brought to the forefront of geopolitics following the current prospects of Global Warming, also emerges the universality of the strategies and logics of behavior of men of all times, from remote prehistory to the contemporary world, who in different eras have found themselves cyclically facing substantially similar problems and situations. This is the concept synthetically expressed in the Latin phrase, taken from a biblical passage, ‘Nihil sub sole novi’ (“There is nothing new under the sun”).

We believe that the best way to close these reflections is to recall the phrase by Enrico Turolla that we cited in the Introduction, referring to the story of the island of Atlantis: Plato “is the bearer of a voice that comes from further away. He has received; he has arranged; he has not invented; indeed, he has faithfully preserved”.

References

- Cf Clay D (2000) The Invention of Atlantis: The Anatomy of a Fiction. In Cleary G, Gurtler G M. (eds) Proceedings of the Boston Area Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy 15: 1–21.

- Cf https://atlantipedia.ie/samples/greenland/ Moreover, among contemporary scholars who proposed the identification of Atlantis with Greenland, here we cite Marco Goti, author of “Atlantide: Mistero Svelato” (Atlantis: Mystery Revealed), Bologna 2017.

- Turolla E (1964) Dialogues by Plato 3: 142-142.

- 25a. In this article, for the translations of passages from Plato's Dialogues we stick to the translation by W.R.M. Lamb, “Plato in Twelve Volumes”, Vol. 9, Harvard University Press, London 1925.

- Here are the three consecutive Greek adverbs, elegantly translated by Walter Lamb as “most rightly (...) in the fullest and truest sense”: ‘pantelôs’ (“perfectly”), ‘alethôs’ (“really”), ‘orthótata’ (“most rigthly”). This attests to how certain Plato was of the existence of the continent beyond the ocean.

- 24e-25a.

- Vinci F (2024) A Hypothesis on the Pillars of Heracles and their True Location, in JAAS 9(3): 1254-1260.

- Plut De Fac 941a-b.

- Plut De Fac 941c.

- As for this topic, cf. also Tsikritsis M (2016) Travelling from Canada to Carthage in 86 AD, Conference Paper.

- Cfr Schulz Paulsson B (2019) Radiocarbon dates and Bayesian modeling support maritime diffusion model for megaliths in Europe, in PNAS 116(9): 3460-3465.

- Castellani V (2005) “Quando il mare sommerse l'Europa”, Turin.

- Gwin P (2024) This incredibly rare burial ground reveals new secrets about the Sahara’s lush, green past. in National Geographic Magazine (Italian edition), Sept. 2024, p. 84.

- Pinna M (1977) “Climatologia”, Turin.

- Plut De Fac 941a.

- Plut De Fac 941d.

- Vinci F (2006) The Baltic Origins of Homer’s Epic Tales, Rochester VT, p. 17.

- De Fac. 941c. Maeotis is the current Sea of Azov (whose extension, as Plutarch states, is actually smaller than that of the Gulf of St. Lawrence).

- Tsikritsis M (2016) Travelling from Canada to Carthage in 86 AD, Conference Paper 1-12.

- The excellent knowledge of geography in Plutarch’s time (1st century AD) is also attested by his statement that the distance from the Moon to the Earth is “fifty-six times greater than the radius of the Earth” (De Facie 925d). Indeed, multiplying the average radius of the Earth (6,371 km) by 56, we obtain an Earth-Moon distance of 356,776 km, while the effective distance of the Moon from the Earth at perigee is 356,500 km.

- De Fac. 941a.

- Libr. of Hist. 5.21.3.

- De Anna L (1993) “The Lost Islands and the Found Islands”, Turku, p. 110.

- The second largest island in the world is New Guinea, which covers 785,000 sq km, much less than half the size of Greenland (and its perimeter is also much smaller than the coastal development of “Libya and Asia together”).

- https://www.britannica.com/place/Greenland

- 118a.

- 113c.

- 118a.

- 118c-d. A stadium is approximately 180 metres, a plethrum is 30 metres.

- 113e; 117a.

- https://visitgreenland.com/about-greenland/hot-springs-greenland/e https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/hot-springs-coexist-icebergs-greenland.

- 113c. Given the importance of this detail, which proves beyond any doubt an accurate knowledge of the geography of Greenland, here we report the transliteration of the original Greek text of the Critias: “Pròs thaláttes mén, katà dè méson páses pedíon ên…”.

- Arnold C (June 2010) "Cold Did In the Norse", Earth Magazine, p. 9.

- Behringer W (2009) Cultural History of the Climate: From the Ice Age to Global Warming, Munich.

- Ortolani F (2001) Environmental integralism and scientific information, in Proceedings of the AIN Study Day 2001, Rome, p. 109.

- https://theinquisitivevintner.wordpress.com/2018/04/01/winemaking-during-the-middle-ages-and-the-renaissance/

- Alley R, Mayewski P, Peel D, Stauffer B (1996) Twin ice cores from Greenland reveal history of climate change, more. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 77 (22): 209-210.

- Pinna M (1977) Climatologia, Turin.

- 118d.

- Grønnow B (1988) "Prehistory in permafrost: Investigations at the Saqqaq site, Qeqertasussuk, Disco Bay, West Greenland". Journal of Danish Archaeology. 7 (1): 24-39.

- “Thyle nunc Island appellatur, a glacie quae oceanum astringit”; Gesta IV, 35.

- Critias 118b. One should consider that the highest mountain in the Greek world, Olympus, does not reach 3,000 meters.

- The pyramids of Giza are located in a place whose latitude, 30°, appears quite significant, also in light of the fact that it is almost the same as the place where the Potala Palace was built in Lhasa, the holy city of Tibet, whose religion presents singular affinities with the Egyptian one (just think of the 42 deities of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which correspond to the 42 ancient Egyptian deities charged with judging the souls of the dead in the afterlife). It is also curious that Giza and Lhasa, in addition to being on the same parallel at 30° latitude, differ exactly by 60° in longitude.

- 115d-116a.

- De Fac. 942c.

- 114e.

- “Great potential for critical raw materials in Greenland”, published 23-06-2023, in https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/greenlands-rich-largely-untapped-mineral-resources-2025-01-13/

- Rowe M (2022) Arctic nations are squaring up to exploit the region’s rich natural resources, in Geographical Magazine, https://geographical.co.uk/geopolitics/the-world-is-gearing-up-to-mine-the-arctic

- 114e. Plato subsequently states that it “sparkled like fire” (Crit. 116c).

- PGE deposits in Greenland, in Exploration and Mining in Greenland, Fact sheet no. 24, 2010. Cf. https://data.geus.dk/pure-pdf/2010_Fact_Sheet_24_PGE_deposits.pdf

- Figure from: PGE deposits in Greenland, in Exploration and Mining in Greenland, Fact sheet no. 24, 2010.

- Platinum versus Gold, in “The Speculative Investor”.

- 117e.

- 25c-d.

- Stride A (1959) On the origin of the Dogger Bank in the North Sea, in Geological Magazine. 96 (1): 33.

- Laviosa Zambotti P (1941) "The most ancient Nordic civilizations", Milan, p. 73.

- White M (2006) Things to do in Doggerland when you're dead, in World Archaeology 38 (4): 547-575.

- Weninger B, Rick Schulting, Marcel Bradtmöller, Lee Clare, Mark Collard, et al (2008) The catastrophic final flooding of Doggerland by the Storegga Slide tsunami, in Documenta Praehistorica 35: 1-25.

- Keys D (2020) How a giant tsunami devastated Britain's Atlantis, in The Independent, 16 July 2020.

- Walker J, Gaffney V, Fitch S, Muru M, Fraser A, et al. (2020) A great wave: the Storegga tsunami and the end of Doggerland? In Antiquity 94(378): 1409-1425.

- Critias 111b-112a.

- Od. 7.80.

- Cf Vinci F (2017) The Nordic Origins of the Iliad and Odyssey: an up-to-date survey of the theory. Athens Journal of Mediterranean Studies 3(2): 163-186. This hypothesis explains all the absurdities, geographical and otherwise, connected with the Greek localization of the Homeric poems, and furthermore allows us to place the Homeric world in its real historical context, that is, the Early Nordic Bronze Age.

- Cf Vinci F (2006) The Baltic Origins of Homer’s Epic Tales. Rochester, VT, p. 213. The fact that early Nordic Athens also extended to islands off the coast links it to the Homeric Thebes (now Täby, near Stockholm) and Mycenae (now Copenhagen), whose names in their Mediterranean counterparts also remained in the plural even though they no longer stood on the seashore. Incidentally, a city founded by Greeks in Sicily straddling the coast and an adjacent island had its name in the plural in both Greek and Latin: Syracuse. Of course, Greek Athens no more resembled its Nordic counterpart, apart from its name, than New York and New Orleans resemble the English York and the French Orléans.

- Tilak B (1994) The Arctic Home in the Vedas, Genoa, p. 263.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jamshid

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yama

- Chiesa Isnardi G (1996) I miti nordici, Milan, p. 186.

- Markale, 1982, p. 76.

- 24:1.

- Shanti Parva 337. Translation from Sanskrit by Kisari Mohan Ganguli.

- In fact, the Homeric poems, which according to our hypothesis mentioned above were originally set in Northern Europe before the descent of the Achaeans into the Mediterranean, often define the sea with the adjective ‘poliós’, “whitish, grey”.

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Narayana-Hindu-deity

- 116 d, e.

- Vemsani L (2021) "Urvashi: Celestial Women and Earthly Heroes". Feminine Journeys of the Mahabharata. pp. 229–241.

- Nat. Hist. 6.79. We also note that on the one hand Dionysus, the “god of Nisa”, as his name indicates, is closely linked to navigation (as appears from the Homeric Hymn dedicated to him), on the other hand in the Epic of Gilgamesh “Nisir” is the name of the mountain of salvation after the Flood. Corroborating this connection is the fact that the name of Liber, also a god of wine, corresponds to that of Mount Lubar, where, according to the Book of Jubilees, Noah planted his vineyard after the Flood.

- Homeric Hymn to Apollo, v. 42.

- Davis G Jr (1946) The Origin of Ursa Major, in Popular Astronomy 54: 111.

- For example, the Seven Hills of Rome were considered the projection of the seven Pleiades on Earth (the argument can also be extended to many other ancient cities on seven hills, such as Jerusalem, Tehran, Armagh, Mecca, Byzantium and many others). Cf. Nissan E; Maiuri A; Vinci F (2019) Reflected in Heaven, Part Two. MHNH 19: 87-166. See also https://www.editorpress.it/en/ovid-the-pleiades-the-secret-name-of-rome-and-other-cities-with-seven-hills

- Revel. 19:16.

- 24:2.

- Saxo, Gesta Danorum 3.6.10 (transl. by Oliver Elton B.A., 1905).

- Cf Vinci F, Maiuri A (2023) Some Striking Indicazionis that the Mythical Elysian Fields Were in Polynesia, in AJMS 9(2): 85-96.

- Surdich F (2015) “Verso i Mari del Sud” (Towards the South Seas). Rome, p. 50.

- , p. 171.

- Italian Encyclopedia Treccani, under "Polinesiani, Antropologia".

- Caillot E (1914) Myths, legends and traditions of the Polynesians. Paris, p. 10.

- De Hevesy G (1933) On an Oceanic writing appearing to be of Neolithic origin, in Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Française, 1933, 30-7-8, 1933, pp. 434-449.

- Tan W (2024) The Coldest Geopolitical Hotspot: Global Powers Vie for Arctic Dominance over Greenland, in HIR Harvard International Review. https://hir.harvard.edu/the-coldest-geopolitical-hotspot-global-powers-vie-for-arctic-dominance-over-greenland/

- Chudley T R, Howat I M, King M D, Emma J MacKie (2025) Increased crevassing across accelerating Greenland Ice Sheet margins. Nat. Geosci pp. 1-12.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...