Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Research ArticleOpen Access

Serpent King Zahhak, a Reality or a Myth? Theorysfields of Literature and Archeology Volume 2 - Issue 1

Hassan Kamali Dowlat Abadi, Mohammad Sadegh Davari* and Hammed Hoseini Rezaei

- Department of Archaeology, Faculty of Humanities, Neyshabur University, Iran

Received: March 12, 2020 Published: May 19, 2020

Corresponding author: Mohammad Sadegh Davari, Master of Archeology, Department of Archaeology, Faculty of Humanities, Neyshabur University, Iran

Abstract

With the discovery and unearthing of signet rings, seals and imprints of these seals remaining from the second and third millennia before Christ, in the eastern regions of Iran, Central Asia and Afghanistan, that carry images and designs similar to the serpent king, and given the fact that these seals are of high documentary credibility for different governments, and even for ordinary people, at present, there is a need for the review and attention of the realistic ideas with respect to the physical life of the serpent king (and the dynasty of Serpent Kings) and presentation of a new image of the Book of Kings. In a new point of view, that is the result of the combination of literature, sociology, archeology, politics, and psychology, a differentiated image of this character has emerged. The results of the research suggest the existence of such a person in real life with two snakes on his shoulders, in view of the throne similar to a snake, interest in charming snakes as pets, and existence of a snake design on the king’s clothing, inculcating in the simple minds of the people of the antiquited that the king is a being of a different entity. Little by little due to his inhumane acts, his opposition with human wisdom, and suppressing heresies that mostly consisted of the young people of the society, his real life changed into mythology, in the form of taking out the young people’s brains and feeding them to these snakes.

Keywords: Zahhak; Iconography; Animalization; Prehistoric; Seals; Material Life

Introduction

The Book of Kings, (shahnameh) is a book of poems in verse composed by Ferdowsi, whol lived in the fourth century after hegira, in the reign of Sultan Mahmoud Ghaznavi, and an Iranian book of historical reference. Shanameh contains many stories that correspond to the Iranian kings, including stories about the rule and kingdom of Zahhak, the serpent king. Ferdowsi says that Jamshid, the king, began to exercise cruelty in the second fifteen years of his kingdom. The people rebelled against him and transferred the kingdom to Zahhak, who had killed his father, Merdas, a farmer and a nice man, and made him the king of Iran. Devil, guised as a skillful cook who cooks diverse and delicious foods for him. After a while, Zahhak asks the cook for a gift. Devil asks Zahhak to let him kiss his shoulders, which is consented. The devil kisses his shoulders and disappears. Two snakes grow out of his shoulders and give the king a lot of pain.

This time the devil appears to Zahhak in the guise of a curandero, and prescribes the brains of two young people to be fed to the snakes so that they would stop irritating the king. So Zahhak kills two young people every day and feeds their brain to the snakes to keep them calm and do not disturb him. It is noteworthy that due to the lack of space in the discs in the ancient times, words of mouth played an important role as a reference in addition to boards. Some of these narrations have been kept in the minds of the people in for form of verse and oral stories which have sometimes been mixed with myths as a representation of reality. Since most of the mythologies have roots in the beliefs of the people, which in turn originate from reality, it is possible to reflect on them and think about the real origins of these mythologies.

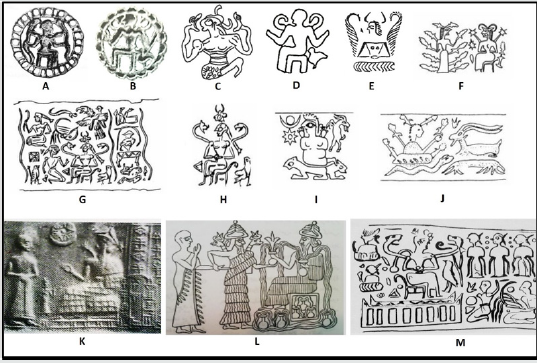

Here, we have different designs of a person with two snakes on his shoulder in some artifacts and figures remaining from the bronze age in Iran and neighboring countries, particularly in Afghanistan and Central Asia, which is suggestive of a character similar to Zahhak from the second and third millennia before Christ.

Adopting the iconological approach of Ervin Panofsky, and anthropologic approach, particularly animatism, this paper seeks to analyze and interpret these artifacts, including the seals, and to analyze the real origin of Zahhak, the serpent king and the dynasty of Serpent Kings, and the metonymy of two snakes on shoulders and their eating of young people’s brains.

Research Background

In terms of art and literature, many researchers have analyzed the story of Zahhak and its relationship with a powerful and cruel king with gods of death and cruelty, but no research has been carried out with respect to Zahhak as a real personality and his life, and this study shall deal with it in the form of a new hypothesis. On the other hand, the research background and the approach taken by this study is iconology and comparative analysis.

Research Method

This research adopts a descriptive-analytic method, and relies on anthropological interpretations and description of the real levels of the artifacts with Zahhak’s designs on them. The population cohort of the present research has been gathered using the library information on the two disciplines of literature and archeology.

Theoretical foundations

It should be admitted that the artifacts of different civilizations represent mythologies and legends that have been popular in those societies and has formed the intellectual and moral legacies of their future generations. In their iconological studies, researchers seek to face the reality of the artifact and try to find out what is that has been carved out in the artifact. Also, they seek to specify the resources indirectly (using literary and religious and ritual sources) or directly (through visual sources and individual ideologies) that has been used by the artist [1]. Iconology poses the question “Why has this artifact been created?” or in more precise terms, “why has the artifact been made this way?” iconological research focuses on the social and historical values of the artifact instead of focusing only on the history of art. Here they discuss how real social developments and the real aspect of the mythologies have been reflected in the artifact. On the basis of such an approach, the artifact is considered an evidence of its own time (ibid: 9-10). Many definitions have been given with respect to ‘myth’ and as such, a myth has a multi-layer meaning, and each time it takes up special definition, and there are different perceptions among every person or every society. These perceptions may play a vital role in the comprehension and identification of the ethnic subconscious structure and pattern of an ethnic group [2]. It should be borne in mind that each of the three levels may be of an ethnic or local origin. This is important to study the iconological studies of the mythologies. Additionally, it should be noted that designs fall into the four categories of 1. Mythological designs, 2. Designs symbolizing gods and divinity, 3. Special symbols that originate from an individual, a group or a special human society and 4. The real position of animals in the everyday lives of he people.

Zahhak, the serpent king, in the pre-historic artifacts (sealses)

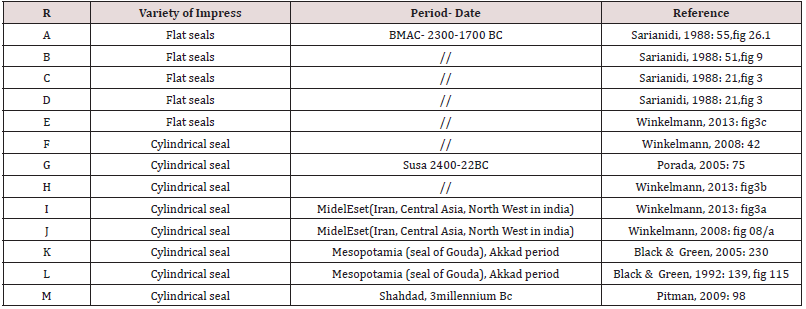

The main research instrument in the present study consists of the signets and signet prints that belong to the third and second millennia before Christ in the Iranian plateau, including Elamite, Shahdad ancient city, Jiroft, Tape Yahya (in Kerman province, Iran), Mesopotamia, Turkmenistan and Afghanistan, and particularly, he cultural zones of Balkh and Marv in Central Asia, that came to highest social, economic and political proliferation, where the rcheologists consider this period as the period of city-dwelling during which social classes, religions, political economy, roads, special transaction networks, such as Khorasan Highways play an important role in the homogeneity of these communities. This homogeneity changed the social structures, beliefs, industrial products, final products, and artifacts or icons of this era in communities. The merger of structures and above factors among different city-dwelling communities led to the formation of integrated and widespread ideologies among the people and elites of these communities, the evidence of which can be seen in the designs and iconographies of the civilizations [3]. Among the most important cultural materials of the city-dwelling and cultural exchanges period is the artifacts that signify ownership, mostly consisting of signets with designs specific to a certain kind of activity, whether political, economic or social, that each had its own proprietor that served as the owner’s signature. From the period under study, signets and signet prints have remained in the process of archeological explorations with personalities with two snakes on their shoulders that refer to the person or persons who used them, and it constitutes a strong evidence in favor of the existence of the real entity of Zahhak with the metonymy of two snakes on their shoulder, which originates from reality and later on, they appeared in Avesta texts and the history of the ancient Iran and in Ferdosi’s Book of Kings, among other few written sources; narrations which have been transferred through the word of mouth and transformed into myths and mythlikes. The mythological levels of these character did not only exist in their overall appearance, but were also manifested in the actions and deeds of the character, his tastes, and favorite objects, as well as from the people’s perception and fear of these characters and their traits. To keep to the scope of the text, one can say that some of the signets with designs of Zahhak, the serpent have been studied in detail by BitaMesbah [4] with briefings on the design. The following section will analyze the designs and the real facets of Zahhak life and the two-snake metonymy and the feeding of young brains to the snakes. Some researchers have attributed these designs to Indo- European gods and goddesses that exist in the traditional beliefs of these people [4,5] (Figure 1&Table1).

Discussion and Analysis

Mythology is the result of the stories of thousands of years ago which have been made available to us through the word of mouth or through the written literature. In myths and mythologies we deal with supernatural heroes and characters that do amazing things. People of the antiquity generalized their mindsets to the whole nature, whether animals, or lifeless things, and personified them in order to justify their interactions. This means animalization. This type of analysis relies mostly on the theories of the school of Nature- Mythology. In the view of the followers of this school, any mythology or reality that is dealt with by mythology is a phenomenon of the natural phenomena [6]. Existence of signets with serpent king designs on them and the proprietorship application for the holder of the signet denotes a reality of the existence of the serpent king as a political figure. Also the existence of a castle in Afghanistan and a castle in the Iranian Azarbayjan in the name of Zahhak Castle (Ghaleh Zahhak) denote the existence of a person or even kings of one dynasty symbolized by the design of a person with snakes on his shoulders stamped on coins , and according to Book of Kings (Shahnameh), with the killing of the last king of that dynasty after a thousand years human societies of that period experience another political and social structure, and such a symbol is vanished afterwards. Animalization has been in the minds of people from thousands of years ago and all of the elements of nature such as inanimate objects, plants and animals were given life and sanity and good or evil spirits who were talked to.

In some parts of the world, such as India, there are still people who believe in these myths. In lexical terms, animalization or giving spirit stem from the word ‘Anim’, translated into ‘Farrah’ in Persian, which as been referred to by Tiller, a British anthropologist in his theory related to the origin of religion [6,7]. In this approach, man deals with this perplex by personifying God and gods and makes stories for them, or even forms families for them and gives them wives, while personifying the natural elements and begins to pray them and sacrifice for them, which is the manifestation of the myths in different regions [6]. Conversely, people, due to their ignorance of the appearance of their kings and the perplexity of the actions of the king, his political and intellectual structures, they visualized the king to be something like a god and describe him with adornments similar to gods, for example of gods of evil and gods of good as viewed by the people that a king may be good or bad as there have been good gods and bad gods. Such a view plays an important role in the analysis of the real life of Zahhak, the serpent king, in the third and second millennia before Christ. Snake is in two ways associated with Zahhak. On the one hand, Zahhak, himself is called a dragon. As it can be seen from Avesta texts, Zahhak is a human being like a dragon or vice versa, that is a dragon in the form of a human, with snakes grown on his shoulders, which is the result of the devil’s kissing them. Snakes that do not calm down unless when they are fed human brains, with the natural consequence of the vanishing of the human species. In most of the ancient Iranian and Islamic texts, snake has been introduced as a devil animal. The design of snake in the Pre-Islam Iran symbolized immortality, fertility, spirit, water, welfare and wealth, land, plants, woman, renaissance and eternity, life and death, moon and sun, and even goddesses. The molting of the snake symbolized immortality and continued life-cycle [8- 12]. Since the snake symbolized death, the immortality lifecycle, and renaissance [8-12]. Its position in the mythological design, especially the prehistoric ones, is indicative of the unique divine power of kings signifies the eternity of their power and the authority of ending the people’s lives by the order of kings. However, with the passage of time, this concept undergoes changes in the eastern Iran and Central asia, because the iconography of these regions snakes are in struggle with animals such as eagles, leopards, and hawk, the latter symbolizing the athlete, which is also indicative of the temporariness of the power of the king [13]. It should be borne in mind that the people of the lower class and ordinary people have played their own role in the narration of the stories by increasing or decreasing the real dimensions of the stories and rendering them myth-like.

With these details and by referring to the administrative evidences (the signets) one may consider Zahhak and his real life as authentic. A person, an elite, with the power of the king ruling a community, who has not been in the view of the ordinary people and even people residing very distant from the throne and has been thought of as myth because of the lack of audiovisual and communication facilities. This has formed a mythological personage because of mixing up his personal traits. It is evident form some of the signets that show a person in the throne of the kings with two snakes upright from both his shoulders. In a realistic analysis, three reality levels may be considered for the explanation of the snakes on the shoulder of the king.

A. The shape of the throne the king was placed in is a high one with ornaments of animals such as horse, lion, snake and so on its armrests. Some thrones had two sculptured snakes on the handle in a three dimensional way. These sculptures sat on top of the king’s shoulders appearing to be grown out of the kings shoulders.

B. On the basis of the existing iconologies remaining from different civilizations and recordings of the kings’ lives in different historical periods, also from the paintings remaining from the medieval period of the kings and the aristocrats interested in pets of different kinds in different periods of time, and considering the real dimension of the snakes in its three dimensions we can conclude that snakes at that time were used as pets, and that Zahhak was interested in keeping and breeding snakes.

C. Most of the clothing of the kings and the elite are made in numerous designs and colors, and a glance at their clothing, particularly clothing of the eastern and far-eastern kings, including Ghour, where Zahhak was born, the design of snakes and dragons on their clothing was quite common.

Therefore, the mythological role of Zahhak and concepts involving different levels of Zahhak’s story, in social, political, literary and ideological terms should not be ignored. The interpretation of the reality levels of Zahhak, evidenced by administrative and political documents proves the existence of such a person, which has been mythologized by the existence of the snakes existing on the throne, pet snakes, and snake iconographies on the king’s clothing, as well as stories made by the ordinary people, with descriptions of the appearance of the kings in them, and the horror felt by the people from the king and its position have turned his real life into a myth. This mythologizing also originates from the cruel acts of the king and his hostility with the people of the community and his pretention of immortality. He mixed the classes of the people by destroying the class system of the previously reigning system (Hassouri), which created abnormalities, such as placement of ordinary people with individual or familial inferiority complexes rising to the ruling class, lack of administrative capabilities among these for ruling the community, which resulted in severe disturbances in the economic and social management of the society. With the destruction of the social classes and occupation of the positions by non-professionals, and existence in the ruling class of people from the lower class of the society that resulted in fluctuations in relations with adjacent governments, the way was paved for the destruction of the social frameworks, increased economic pressures and dissidences in the that was though as improbable in the beginning of his rule, but rising to top of power of a man from non-professional class, lack of competent consultants in politics and international relations, and his absolute rule and limitless power resulted in his hostile reactions, psychotic behaviors. with this perception of this level of cruelty in the king, the people of that time attributed him to subterranean gods or god of death, and due to the horror they had with him, and his eternal power the people may have visualized him a person with snakes on his shoulders. Since the youth are the think tank of the society and due to the fact that these are the people who constitute most of the dissidents among the nations and throughout history due to their idealism, and Zahhak killed, imprisoned his dissidents or changed them into people with no thoughts and aspirations that did not protest the cruel conditions and they were young people who made no difference with dead people, and they and according to a notorious saying, they were resting in vertical graves. This opposition with intellect and wisdom and hostile reactions of Zahhak was transferred through the word of mouth and this condition is manifested in the mythologized story of feeding young people’s brains to the snakes, a symbol of suppressing wisdom and thinking [14-18].

Thus the artifacts and printed evidence of the signets that only belonged to the elites, evidence the realities of the lives of mythological people, particularly Zahhak, the serpent king. Numerous signets from ancient cultural sites signify the existence of a wisdom-fighting and cruel dynasty and the use of iconography as a symbol of their dynasty and an emblem for their governance.

Result

The results of our study, given the reference to the story of Zahhak, the serpent king, appearing in Ferdosi’s Book of Kings, as well as description provided by Ferdosi of the attribute of such a king and similar kings and their dominance over the communities as wished by the people, and kings who consider ruling as an absolute right without thinking about their precedence and their original social class, and who believe in their eternity and immorality. They consider the only way to defend themselves as opposing with the young people and their brain, ideas and thoughts. So they always seek to destroy and decade the young people and deplete the community from the brains of the young people and intellectuals. And Zahhak, the serpent king and the Zahhakian (Zahhaks) dynasty with the emblem of snakes represent these kings. In addition, animalization as iconoclastic analysis, it is possible to prove the material life of such person or persons who used the snake symbol for his own personal preference and, in three cases used in the royal throne, raised snakes as Pets or even icon paintings on the king’s clothing, he is merged into the legend of the people of the lower classes of society and, for lack of a realistic picture of the king of society, his symbol and iconography are introduced into the mythical creature’s beliefs. This belief has gradually formed the symbol of this person or dynasty in the form of a bead appears on her shoulders in a personal role with two snakes.

Result

- Nasri A (1391) Image reading from the perspective of Ervin Panofsky. Chemistry of Art Quarterly, (6): 20-7.

- Taheri S (1394) Exploring the concept of a symbol (an ancient study of the snake pattern in Iran and neighboring lands). Journal of Fine Arts - Visual Arts 20 (3): 25-34.

- Basfa H, Davari MS, Rezaei M (2015) Assessment of Serpent Iconography in Cultural Zones of Iran and Central Asia in Bronze Age: Emphasis on Stylistic Changes and Mythical Concepts. Study pre-Islamic archaeological 1(2): 17-30.

- Mesbah B (2018) Ancient depictions of the Zahak myth in Iran based on motifs on the seal of the periodElamite (3rd millennium BC). Art and Urban Garden Magazine 14(56): 43-56.

- Khatibi A (2001) Again, the story of Zahak Mardoush. Art Month Book, p. 56-58.

- Tahani T, Tavakoli D (2016) A Study of means animalization in Iranian Myths and Literature. Quarterly Review of Literary Criticism. 11( 43): 95-109.

- Soleimani Ardestani A (2003) Primary and Silent Religions. Qom: Love Ayat.

- Van Buren E D (1934) The God Ningizzida. Iraq 1(1): 60-89.

- Golan A (2003) Prehistoric religion: Mythology, symbolism. Ariel Golan, Jerusalem.

- Frazer JG(1919) The folklore in the Old Testament. Macmillan, London, United kindom.

- Moradi H (1394) The origin of the role of the snake in the cultural materials of the third millennium BCE southeast of Iran: A sign of connection with Elam and Mesopotamia. Archaeological Studies 7 (2): 148-131.

- RafiFar J, Malek M (2013) Iconography of the leopard and snake icon in Jiroft, the third millennium BC. Iranian Archaeological Research 3 (4): 7 -36.

- Basafa H, Davari MS (2019) Khorassan Intercultural relations with southeast of Iran and Western Central Asia in the Late Bronze Age Case Study: The Silver artifact of ShahrakFirouze in Neyshabour. Archaeological Research of Iran 9(21): 79-96.

- Black J, Green A (1992) Gods, Demons and Symbols. Trancelate in PeymanMatin. Ancient Mesopotamia, London, United kingdom.

- Pittman H. (2013) Imagery in administrative context: Susiana and the West in the fourth millennium BCE. Ancient Iran and Its Neighbours: Local Developments and Long-range Interactions from the Late 5th to the Early 3rd Millennium BC. pp. 293-336.

- Sarianidi VI (1998) Myths of ancient Bactria and Margiana on its seals and amulets. Pentagraphic Limited, Moscow, Russia.

- Winkelman S (2008) Animali E Meti Nel Vicno Oriente Antico: Un,analisiAttraverso I Sigilli. I disegni a corredo del testosonostatieseguitidall’Autore.

- Winkelman S (2013) Trasformation of Near Eastern Animal Motifs in MURGHABO-BACTRIAN Bronze Age art. Animals, Gods and Men from East to West Papers on archaeology and history in honour of Roberta VencoRicciardi. BAR International Series 2516 p. 47-64.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...