Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Research Article(ISSN: 2690-5752)

New Perspectives on Xinjiang Kangjiashimenzi Petroglyphs (P. R. China) Volume 8 - Issue 2

Augustin FC Holl1* and Emma Borjigid Bohm2

- 1Department of Anthropology and Ethnology, School of Sociology and Anthropology, Africa Research Center, Belt and Road Research Institute, P. R. China

- 2Department of Anthropology and Ethnology, School of Sociology and Anthropology, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, P. R. China

Received:April 24, 2023; Published: May 16, 2023

Corresponding author:Augustin FC Holl, Department of Anthropology and Ethnology, School of Sociology and Anthropology, Africa Research Center, Belt and Road Research Institute, P. R. China

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2023.08.000283

Abstract

The Kangjiashimenzi petroglyphs discovered in the 1980s by Professor Wang Binghua and popularized by Dr. Jeannine Davis-Kimball have generated an extraordinary range of interpretations ranging from crude sexual overtone to more sophisticated ritual practices. The interpretation of past visual representations is fraught with theoretical and methodological difficulties, one of the most damaging being the projection of the present into the past. Selecting relevant images supporting the narrative one wishes to craft seems to be the common research strategy. Images or icons tend to be polysemic. This article offers a global iconographic approach to past visual representations that takes into consideration all the variables and parameters drafted by the “image-makers” in a kind of re-enactment of the image-making process. The analysis is articulated on a hierarchical systematics starting with

a. Drafting “element” (line or surface), combined to form.

b. Motifs, that are at their turn arranged in

c. Clusters, adjusted in

d. Scene, that finally generate.

e. A composition or narrative.

Read from such a perspective, and considered from the perspective of Xiaohe people cultural landscape, the Kangjiashimenzi petroglyphs appear to have been a “textbook” used in the performance of the rites of passage from childhood to adulthood for boys and girls in their distinct initiations.

Keywords:Xiaohe Tradition; Kangjiashimenzi; Petroglyphs; visual representations; Iconographic approach; Iconographic syntax; Rites of passage; Xinjiang; China

Introduction

Geographic and chrono-cultural Contexts of Kangjiashimenzi Petroglyphs

Kangjiashimenzi petroglyphs rock-shelter was discovered in the 1980s by Professor Wang Binghua. It is located in Quergou village in the southwestern part of the Hulubi county on a low hill cliff at the northern foot, at 35o 58’ 29.496” North latitude and 76o 33’ 21.24” longitude East at the northern foot of the Tianshan range in the Xinjiang province [1-8]. The site is a 50 m wide shallow rock-shelter located at the base of a 300 m wide and 180 m high vertical sandstone cliff (Figure 1). “The dripline is up to 28 m above the present shelter floor. Much of the shelter wall as well as some blocks on its floor are covered by hundreds of petroglyphs and some inscriptions” [8].

Figure 1: View of Kangjiashimenzi rock-shelter at the foothill. (Source: https//:www.farwestchina.comblogkangjiashimenzi-prehistoric-petroglyphs).

The recorded petroglyphs are carved at height ranging from 10 to 2.5 m above the present-day ground floor. “It is likely that this main panel was created when the floor was several meters higher, and the creek at the base of the slope below the site may have caused the erosion of the berm deposit” [8]. The sitting of the petroglyphs appears to have been selected very carefully based on its natural characteristics and potentials. It is located in a rock-shelter at the foot hill protected from cold winds, rain and snow. A spring providing water is about 30 m away. “The sanctuary was used over a long period of time as evidenced by a 2 m layer of ash found on the flat ground in front of the monument” [2,9]. The images drafted with chisel/hammer technique are carefully polished, some of them preserving evidence of red, yellow, and white paint. They are spread over a surface 14 m long East-West and 9 m wide from bottom to top. Most of the images are however concentrated on approximately 60 m2 [8,9].

The reported Kangjiashimenzi petroglyphs have been sub-divided into 8 main groups by Wang Binghua (1990, 2010). They are dated predominantly to the first half of the second millennium BCE, corresponding to the Middle Bronze Age and assumed to belong to the Xiaohe Culture [9,10]. The Xiaohe Culture or Tradition, documented principally from two cemetery sites, Xiaohe and Gumuguo, is considered as the most extraordinary of the Central Eastern Asia Bronze Age entities. It is predominantly aceramic, relying on wood, plant fibers and animal leather for its material culture products [11-14]. It emerged in the center and east of Tarim basin in southern Xinjiang, its earliest phase dated to 2200-1880 BCE.

Xiaohe people subsistence systems were essentially articulated on the exploitation of lacustrine and riverine resources, cattle husbandry, and small scale cultivation of wheat and barley. The excavation of 167 burials from Xiaohe Cemetery has produced an extraordinary array of material culture. It includes “numerous large phallus and vulva posts made of poplar, striking human figures and masks, well preserved boat coffin, leather hides, wheat and millet grains, and many artifacts” [15]. Paleo-environmental and aDNA research has started to shed light on the entangled population history of central-eastern Asia, with focus on the Tarim basin of Xinjiang province [15-19]. For Wang et al (2021) for exa of the Bronze Age Tarimmple, ancient Xinjiang mitogenomes reveal intense admixture with high genetic diversity. Fan et al (2021) look at the genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies. They sampled 13 individuals from the Tarim basin dated from 2100 to 1700 BCE and found, on the one hand that they display local ancestry with strong evidence of milk protein. And on the other hand, that the earliest Tarim basin cultures arose from a genetically isolated population that adopted agricultural and pastoral lifeways from their neighbors. Finally, [15] analysis of ancient human mitochondrial DNA from the Xiaohe cemetery revealed the presence of a wide variety of maternal lineages, originating from Europe, Centra/Eastern Siberia and southern Western Asia.

The Kangjiashimenzi petroglyphs are almost unanimously dated to the Middle Bronze (ca. 1900-1500 BCE) and attributed to the Xiaohe culture or Tradition. Since their discovery by Professor Wang Binghua in the 1980s, this extraordinary series of ancient visual representations has generated an endless cycle of interpretations including pornographic themes [20]. For [5] the cast of 100 figures presents what is obviously a fertility ritual. For [9] the site features “a giant tableau… essentially a detailed representation of ancient mystical ceremonies associated with ancestral and tribal cults and sacred ritual of marriage”. For Zabiyako and Wang [21], the phallic images and female signs are visual expressions of the fundamental to archaic consciousness idea of child bearing, reproduction, continuity, and unity of generations originating from one common ancestor”. For Davis-Kimball and Behan [3], it is a display of ancient fertility rituals in the Tien Shan. Generic interpretations of past visual representations, as plausible as they can be say a lot more about contemporary researchers views than about past societies worldviews. All ancient visual representations researchers are well aware of the theoretical and methodological difficulties and traps hidden in their efforts to decipher past peoples thought. “When interpreting ancient monuments of figurative art we often fail to understand the specific context of a scene that embodies an ancient mythologem. It is especially difficult to reconstruct the meaning of individual human or animal figures since they may act as symbols while the semantics of the whole image was dictated by lost context” [4]. However, one does not have to abandon the arduous task of searching for an accurate and deeper understanding of past visual representations. All contemporary researchers, even those from direct descent from the past societies under consideration are outsiders in regard to the meanings of the depicted images. The task of interpreting these past ideas shaped in images has to be anchored on sound and explicit falsifiable theories and methodologies [22].

Theory and methods: The iconographic approach

Theoretical Perspectives

It is crucial for past makers of visual representations to be taken seriously. A society does not create visual representations; some individuals belonging to that society do. The place and role of these creative minds in their respective societies has to be taken into consideration in any theoretical modelling of the role of visual representations in their respective and even contemporary societies. There are two complementary aspects to the production of visual representations: individual disposition and representational gift and learned technical skills [23]. Some artists succeed in initiating styles and mode of representation that become dominant and virtually synonymous to their societies within the dominant cannons.

The patterns of gesture and manual skills involved in the creation of visual representations mobilize a range of tools and body motions. In the case of Kangjiashimenzi petroglyphs they consist essentially of chisel and hammer for pecking and carving on the one hand and surface polishing on the other hand. The featured craftsmanship displays a high degree of carving expertise. The implemented operational sequence (Chaine operatoire) involved.

a. Pecking.

b. Successive pecking strokes to grove lines.

c. Successive grooving events to finish the outline et elements of the representation.

d. Fine polishing of the delineated surfaces; and finally

e. Use of white, yellow, and red paint.

All pictorial components, size, position, location, orientation, association, color, etc. matter in a visual representation and are used to convey a sense of the narrative to those having access to the cultural code. For outsiders, the optimal strategy to approach the plausible meanings of ancient visual representations is to patiently replicate the creation process, “deconstruct” the multiple levels of assemblages, and re-assemble the pieces in the most parsimonious explanation integrating the maximum of possible options.

The Iconographic approach

The iconographic approach to past visual representations was designed to move away from dominant typological and chronological taxonomies to insert agency, intentionality, uncertainty in this peculiar category of the archaeological record. All the case studies selected so far have been picked from Africa, in the Sahara as well as Southern Africa [24-33]. Images in visual representations as words in verbal communications can be ambiguous and/or versatile with multiple meanings. It is accordingly their context of expression that can assist in narrowing the range of options. Researchers are supposed to decipher what can be termed the “iconpgraphic syntax” used in any visual representation under consideration. Spoken language is made vowels and consonants. Words are made of variable combinations of phonemes [sound units]. And finally, speech is based on variable combinations of words to certain rules – syntax - that vary from one language to next. The concept of “iconographic syntax is based on that analogy and can be delineated as follows:

a. The drafting element: They consist of the elementary components of any image. Line segment drafted in quick succession, arm, fore-arm, lower leg, etc.

b. The motif: a combination of drafting elements produces a motif, an identifiable entity, a person, an animal, an object, etc.

c. The cluster: a cluster of motifs based on their spatial location and relative provides a sense of an action being carried out, choreography, combat, celebration, etc…

d. The scene: a scene features a combination of actions that can be either simple and straightforward or complex multi-iterated, dance performances, etc.

e. The Act: an act is an adjusted series of scenes that is generally designed as such by the maker(s) of the visual representation.

f. The narrative: It is the sum-total of the cultural messaging featured in a site with large-scale visual representations. It includes later additions and/or erasure of previous motifs, that may still make cultural sense [34,35].

The method outlined above is applied to the Kangjiashimenzi petroglyphs, through a conjecture and refutation procedure [22] in an attempt to derive a verifiable and falsifiable reading of the monumental composition.

Reading Kangjiashimenzi Petroglyphs

Act I

Act I is drafted at the top-left of the rock-shelter panel. It is made 29 images distributed in 4 categories: humans, masks, animals and objects. The representations feature 17 humans: 10 males, 4 females, 3 ungendered; 7 masks, 2 animals and 3 objects (Table 1, Figure. 2). Act I visual representations choreography is organized in 3 scenes, from the left to the right.

Scene 1

Scene 1 at the left end of Act I is made of 12 images, 5 humans: 3 ihtyphallic males and 2 females; 2 quadrupeds, and 3 bow-arrows sets, arranged in 4 narrative clusters (Figure 2). Cluster 1 includes Individual 1 and 2 engaged in intercourse. Individual 2 has a 2-antenna headgear, two parallel lighter vertical and parallel bands on the upper torso, a tail and an unidentified object hanging at his right elbow. Individual 1, the female faces individual 2 with spread legs. Cluster 2 is made of individual 3 and 10, and mask 4. The mask 4 is drafted under the raised right arm of the female Individual 3 who is drafted in plain face view. Individual 10, the male character drafted on the left side of the female, is headless. Cluster 3 is comprised of 5 images, two quadruped animals 6 and 9, drafted in profile view facing right [from the reader viewpoint] and 3 bow/arrow sets (5, 7, 8). Both long-tailed animals, clearly male, seem to feature an adult and a young specimen. The three bow/arrow sets are targeting animal 6 and not the younger individual. Finally, Individual 12 at the bottom right end of the scene replicates the posture of Individual 2. He is ihtyphallic, drafted with a tail, and appears to face off with the quadrupeds. All the represented humans display an identical arms posture, the left arm folded at elbow and turned down, and the right one, bent at elbow and turned up, with open palms. It is worth emphasizing that all three males present slightly flexed legs, oriented left.

Scene 2

Scene 2 is located at the center of Act I. It is comprised of 12 images, essentially humans and 4 masks (Figure 2, Table 1). The scene is focused on sexual intercourse, with all the humans drafted around the female Individual 14. She is drafted at the center of the scene with the legs widely stretched, with the standard arm posture, the left arm down, and the right one up, as if holding her head. The images are arranged in 3 distinct clusters, each combining a large and a small human. Cluster 1, in the top left, is made of the non-gendered small human 11 drafted behind and in direct contact with the larger male 13. The latter has a particularly long left arm, folded at elbow above the shoulder. The right arm is suggested but concealed by the head of individual 11. Cluster 2, in the center replicates the topology, with the small non-gendered small human 15 drafted under the right arm of the much larger male, Individual 16 (Figure 2). The latter is featured with some particularities. He is wearing a two-antenna head-gear and has two pairs of “arms”. The right arm’s set is made of one straight line connected to individual 13 left elbow, while the other is bent upward at elbow, holding an unidentified object, the hand palm wide open with 7 “fingers”. The left arm’s set includes a straight fore-arm pointing down from the shoulder and a complete specimen, folded at elbow slightly above the shoulder, pointing down with the hand palm open and featuring 7 “fingers”. Finally, a relatively large mask (17) was carved on the torso and chest of Individual 16. It features the “2-antenna” headgear and a beard. Cluster 3 is located at the bottom right of the scene. It includes the large male Individual 20, the smaller non-gendered Individual 18, and mask 19. Individual 20 featuring the standard arm’s posture has a peculiar head-gear. His right arm represented up to the elbow was carved on top of Individual 16 (Figure 2). Mask 19, may have been an attempt to replicated the duos 11-13 and 15-16, but was aborted because of the lack of space. Individual 18, non-gendered and displaying the standard arm posture was carved instead where there still some space available. Finally, Image 21 (Figure 2), considered as a Mask in the description but featuring a neck, was very clearly an aborted human representation. It did not fit in the iterated narrative and was stopped short.

Scene 3

Scene 3 is drafted at the right end of Act I. It is comprised of 10 images featuring humans and masks (Figure. 2, Table 1). As indicated by motifs superimpositions, scene 3 was drafted in two distinct and successive episodes. The initial episode is made of 9 images arranged into two sets. The top cluster 1 with individual 23, 24, 25, and mask 22 features what look like sexual intercourse between female Individual 23 and male Individual 24. The latter presents an arms posture opposite to the standard one recorded so far, with a raised shortened left with an open hand palm and a right one bent at elbow and turned down. Individual 25, drafted from the hip up is ungendered, wearing a twin-antenna headgear, features the standard arms motion, the left arm bent at elbow and turned down, and the right one folded and raised. The bottom cluster, partly obliterated by latter superimpositions is made of 3 more or less comparable size ihtyphallic males 27. 30 and 34, and two “horn-like” (31) undetermined representations. Male 27, with his left arm partly concealed features the standard arm posture, has a twin horn representation above his right shoulder. Male 30 is almost entirely obliterated with only his legs slightly bent rightward and erected penis visible. And finally, Individual 34, also featuring rightward slightly bent legs is drafted with the standard arm posture.

The mask 28, the double-head Individual 29, and Individual 35 were drafted in the second episode and painted in red (Figure 2). Mask 28 was carved on Individual 27 torso. The arms of Individual 29, drafted in the standard posture were proportionally reduced in size to fit in the available space and above the head of Individual 27 of the right and 34 on the left. The twin-head are adorned with a two-antenna head-gear and the hour glass body shape point to a female representation. Finally, Individual 35, drafted at the right end of the scene, very likely representing a female based on the body shape, wears a twin-antenna headgear, the arms in the standard posture, with however a tail tilting toward the male organ of Individual 34. The celebratory tone of scene 3 suggested by the choreography of Individual 27, 29, 30 34, and 35 legs is unmistakable. Act I is comprised predominantly of male representations even for the both quadrupeds (Figure 2). Each scene includes a single depiction of sexual intercourse, Individual 1 and 2 in scene 1, 14 and 16 in scene 2, and 23 an 24 in scene 3. If female individuals 29 and 33 and mask 28 drafted in a second episode, as well as all the represented mask are not taken into consideration, all 3 scenes are made of 7 images each. The females from Act I are clearly represented in diminutive size and the whole imagery appears to gravitate around the central sexual intercourse of male individual 16 and female Individual 14.

Act II

Act II drafted in the top right side of the previous one is made of 13 images, 1 mask, 2 pairs of horses (stallions), one male, and 9 females (table 1, Fig. 3) that appear to be arranged into 2 bi-laterally symmetric scenes. Different but complementary readings of the staged choreography are possible. In the first one, the male Individual1 drafted in the left margins is withdrawn from the stage choreography. In that perspective, scene 1 and scene 2 are perfectly symmetric on the left and right of Individual 7. Individual 1, at the left end of scene1 is tilted as if laying on his back. He is wearing a twin-antenna headgear and feature a unique posture with both arms raised. Individual 7, at the center of the act is singled out by a double twin-antenna head-gear (Figure 3) and appears to play a key structuring role in the act.

Scene 1

Scene I in the left half of the act is made of 4 females, one mask and 1 pair of fighting stallions (Figure 3). Remarkably, the size of the drafted characters increases from the left (Individual 2) to the right (Individual 6). All females perform the standard arm posture. The smallest individuals 2 and 3 are devoid od head-gear. The larger one, Individual 4 and 6 have twin-antenna head-gears. The fighting stallions (Image 5) and the mask (Image 13) are drafted on the left of Individual 6, the former under her bent right arm, and the latter along her right knee.

Scene 2

Scene 2, drafted in the right haft of the act, made of 5 images, 4 dancing females and a pair of fighting stallions (Figure 3), replicates the patterning observed in scene 1, with the size of the drafted representations increasing from the left (Individual 8) to the right (Individual 12). The fighting stallions (Image 9) are drafted under right arm of Individual 10. Individual 8, 10, and 11 are wearing twin-antenna head-gears, while Individual one has a single antenna. In the second reading, the women choreography is structured in patterned triangular moves with shifting apex involving individuals of different size (Figure 3). It is the case for Individual 2-3-4 in the left, 6-7-8 at the center flanked on the right and left by fighting stallions, and finally, 10-11-12 in the right. Differential size may have been a technique to insert a third dimension in the representations, and in this case perspective. The movement inferred from this reading of the evidence which includes the male Individual 1 features a succession of wave-like riddles with increasing amplitude from the left (Individual 1) to the right (Individual 12). It starts with Individual 1, down to Individual 2, up to Individual 3, and down to Individual 4 in scene 1. Then followed by Individual 6, down to Individual 7, and Up to Individual 8 in scene 2. And finally completed by Individual 10, down to Individual 11, and slightly up to Individual 12 in scene 3 (Figure 3). The central triplet 6-7-8 from scene 2 is bracketed in bi-lateral symmetry by pairs of fighting stallions: pair 5 in the left with their sex attributes well delineated and pair 9 in the right without. It is also worth emphasizing the fact that male Individual 1, stallion pair 5 and pair 9 are equidistant from one to next, featuring “male principle” in this predominantly female act.

Act III

Act III is staged at the gravity center of the global Kangjiashimenzi petroglyphs narrative. Literally encapsulated, drafted on the right of act I and below act II, it is comprised of 13 images articulated in 3 scenes (Table 1, Figure 4).

Scene 1

Scene 1, located in the top-central part of the act is made of 5 images, 3 humans, 1 mask, and one undetermined representation (Figure 4). Individual 1, on the left side represent a male character, featuring the standard arms posture with his left hand holding his oversize penis directed at the female Individual 2. The later, represented in face view wears a twin-antenna head-gear and displays the standard arms’ posture with the left hand “holding” Individual 3. Individual 3, an un-gendered person with a single-antenna head-gear is drafted in an unusual horizontal position across Individual 2 torso, its head in the right and legs in the left. Its arms are in contact with Individual 2, the right one on the left shoulder and the left one on the torso. Image 7 is difficult to identify. It has the appearance of a “quadruped” long-tailed animal oriented left-right. Mask 8 is superimposed on the large quadruped 7 next to a small quadruped 9. Without having to over-stretch the imagination, scene 1 features a social microcosm made of the representations of an adult male (Individual 1), and adult female (Individual 2), possibly a grown child (Individual 3), domestic animals (7 and 9), and the mask as cultural symbol.

Scene 2

Scene 2 made of 3 representations is drafted in the top-right part of the act (Figure 4). It is made of 3 ihtyphallic males, Individual 4, 5, and 6 featuring the standard arms’ posture, and all turned left toward the female Individual 2.

Scene 3

Scene 3, located in the bottom half of the act is made of two clusters. Cluster 1 in the right is comprised of 3 humans engaged in intercourse (Figure 4). Individual 10, in the bottom left of the trio is androgyne, and combines female body shape with an elongated penis. Individual 11, the female character represented with legs wide open features the standard arms’ posture. Finally, Individual 12, a male character is represented with flexed legs and both arms raised as is the case for Individual 1 in Act II scene 1. Cluster 2 features a farandole, an open-chain dance of miniature humans, originating from the female Individual 11 (Figure 4). It is arranged in two parallel lines proceeding from the right to the left, with the upper line made of 23 and the lower one of 20 shadowy small humans. The metaphor of biological and social reproduction is clearly stated in this cluster.

Act IV

Act IV is drafted on the right of the previous one, below Act II, and along a top-left – bottom-right diagonal. It is comprised of 31 images distributed into 16 humans, 9 male, 4 female, and 3 un-gendered and 15 masks arranged in four aggregates articulated on s distinctive central character (Figure 5).

Outlier 1

Outlier 1, made of three images, 2 humans (Individual 2 and 3) very likely male and mask 1 are drafted at the top-left center of the act (Figure 5). Both humans represented with tails display the standard arms’ posture, with Individual 3 either an exfoliated head or headless character.

Outlier 2

Outlier 2 in the top-right center part of the act is the female counter-part of Outlier 1 (Figure 5). It features two females with the standard arms’ posture, one complete (Individual 1) and the other legless (Individual 2) drafted in sub-horizontal position and oriented left-right.

Scene 1

Scene 1, staged in the bottom left half of the act is comprised 11 images, 7 humans and 4 masks (Figure 5). The different orientations of the male characters, Individual 5, 8, 10 and 11 are drafted in the bottom-left and top-right of the diagonal axis connecting female Individual 4 and 12. The later drafted at the center of the configuration with arms in the standard posture holds a stick-like object in her left hand. The large male Individual 5 wears a triple-antenna head-gear, a horse-shoe-shaped collar, and a tail. His right arm is forked at elbow suggesting the presence of a stick-like object. Individual 7 with the neck and shoulder line drafted and partly superimposed on Individual 6 is very likely an abandoned initiative, not a mask. The spatial distribution of masks 6, 9, 13, and 14 seem to delineate the perimeter of the scene (Figure 5).

Scene 2

Scene 2 is drafted in the bottom-right half of the act. It is made of 4 humans and 13 masks. The featured humans include two males (Individual 5 and 14), an androgyne (Individual 4), and an un-gendered person (Individual 8). Both males, one with a tail, are turned toward the androgyne Individual 4. The later, wearing a twin short antenna head-gear, displays the standard arms’ posture, with the extended left arm put around Individual 5 shoulders (Figure 5). As reported on scene 1, masks 3, 6, 7, 10. 11, 13, 15, 16, 17. 18, and 19 delineate the perimeter of the Scene 2 too.

The Central Character

The recorded pattern of superimposition shows the Central character to have been drafted on top of a mask at the upper legs level, obliterated left arm of Individual 8 (Scene 1), and its penis superimposed on the same Individual 8. The body shape suggests the central character to a tailed androgyne, wearing a floating scarf (Figure 5) with both arms raised. The image was accordingly inserted skillfully in a pre-existing creation. The raised hands directed at Outlier 1 and 2 and in direct contact with scene 1 and 2 connect all four pictorial sub-units of Act IV.

Act V

Act V, drafted on the right flank of Act IV and comprised 15 images, 5 humans, 3 quadrupeds, and seven masks is articulated in 3 brief scenes (Figure 6, Table 1).

Scene 1

Scene 1 is located in the top-left part of the act. It is made of 1 human representation (Individual 2) in central position surrounded 7 masks. Based on body-shape, Individual 2 is likely female, drafted with incomplete limbs (Figure 6). The arms drafted up the elbow are stretched horizontally. The 7 masks are arranged in a horse-shoe pattern, Mask 6 under the right arm, Mask 1 and 3 above the shoulders, respectively on the right and left of the head, Mask 8 at the left hip flank, and finally, Mask 7, 9, and 10 in a vertical alignment under the left arm.

Scene 2

Scene 2 on the left of the previous one consists of 3 humans all in upright position with the standard arms’ posture (Figure 6). Individual 4 on the right is very likely female based on body shape. Individual 5 in the left is a male. And finally, Individual 11 drafted in the middle below Individual 4 and 5 arms is either un-gendered or androgyne.

Scene 3

Scene 3 is located at the bottom left of the Act. It made of 4 images, one human and 3 quadrupeds (Figure 6). Individual 12, drafted with the standard arms’ posture is represented from the abdomen up. The 3 quadrupeds, animal 13, 14, and 15, drafted on the right flank of Individual 12 are oriented left, and set in a diagonal bottom-left – top-right perspective. The represented mammals are difficult to determine, but based on Act 2 precedent, they may represent horses. Act V thus features a relatively large size female Individual 2 surrounded by 7 masks in scene 1, the microcosm of gender diversity in scene 2, and finally, human in company of animals in scene 3.

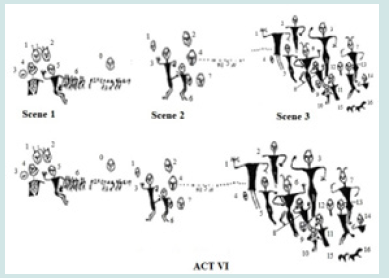

Act VI

Act VI is located in the center left of the composition, below act IV and V. It is clearly an “organic whole” designed as such by the makers of the petroglyphs. It is made with 31 images arranged in 3 scenes (Figure 7, Table 1).

Scene 1

Scene 1, staged at the right end of the act consists of 2 individuals, 3 masks (1, 2 and 3, and an alignment of miniature people (6). Individual 4 is sketchy and drafted from the hip up without limbs. Individual 5 on the left featuring the standard arms’ posture is a male represented with slightly flexed legs turned left (Figure 7). Finally, the miniature people alignment 6 on the left flank of the scene, featuring a left-right movement, is a direct connector to the rest of the act via the intermediate link 0. The latter is made of Mask 0 above, and the row of miniature people below.

Scene 2

Scene 2 on the left of the previous one and in the central portion of the act is made of 8 images, 2 humans (Individual 3 and 6) and 5 masks (1, 2, 4, 7 and 8), 1 row of dots (5) representing “potential” miniature people in the making. Masks delineate the upper and left perimeter of the scene around the humans’ representations. Both individuals feature the standard arms’ posture. Based on the slightly flexed legs orientations, Individual 3, the male and Individual 6, either female or androgyne are face to face (Figure 7). It is also worth noting that Individual 6 is partly superimposed on mask 8. Finally, 5 the last element of the scene, a connector between scene 2 and the next one features a “transformation process” that will be discussed later.

Scene 3

Scene 3 drafted at the left end of the act is comprised of 16 images, 12 humans, 2 masks and 2 quadrupeds (Figure 7, Table 1). Individual 1, 2, 3, and 7, set along the upper perimeter of the scene feature the standard arms’ posture, with however Individual 1 headless. The scene appears to be articulated around the episode of sexual intercourse between Individual 10, the female and Individual 11 the male, and Mask 9 set in the central bottom part. There are 2 clusters of 3 individuals each drafted on the right and left of this central episode.

The right cluster is made of Individual 5, 6, and 8, probably female for the former 2, and male for the later. Individual 6, wearing a twin-antenna headgear, was drafted above an anterior human whose slightly flexed legs are visible on her right flank (Figure 7). A closer look reveals that Individual 6 (the female) and 8 (the male) feature completely unusual arms’ postures. Individual 6 has her right arm folded at elbow and touching the torso. Individual 8 has both arms bent at elbow with both arms raised. The left cluster, with images 12, 13, and 14 is much more schematic. Individual 12 is represented by head and neck, Individual 13, armless with a tail, and finally Individual 14, with upper torso, right arm and head. Two unidentifiable quadrupeds, animal 15 and 16, drafted at the bottom left of the scene, are moving leftward. Scene 3 features a core cultural event, a core sexual encounter celebration that sustains social reproduction materialized by a row a small to larger dots to start with from Scene 3 to 2, then the emerging miniature to full miniature people from Scene 2 to Scene 1 (Figure 7). The allegory, “of biological and social reproduction”, framed in images in Act 7 is unmistakable. Some may call it “fertility rites” but as will be shown later such a generic interpretation can be misleading.

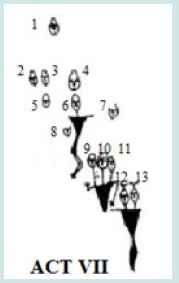

Act VII

Act VII comprised of 13 images an arranged along a top-right – bottom-left diagonal is located at the bottom left end of the composition. It includes 4 sub-sets. Sub-set 1 at the top-right is made of masks 1, 2, 3 and 5 (Figure 8, Table 1). Subset 2, also made of 4 images includes 3 masks (4, 7, and 8) and the un-gendered Individual 6 drafted with truncated arms and slightly flexed legs oriented left. Sub-set 3 consists of a three-headed Individual 9-10-11, represented from the torso up featuring the standard arms’ posture. And finally, sub-set 4 at the bottom-left end, displays a double-headed Individual 12-13 with truncated arms, likely female based on body shape, wearing twin-antenna head-gear (Figure 8). Act VII is overwhelmingly schematic with masks and heads representations as leitmotivs.

Structure of the Kangjiashimenzi Narrative

Kangjiashimenzi petroglyphs are clearly palimpsestic in nature, drafted very likely by different “artists” over a period of unknown duration. The complete composition is organized in 8 acts arranged from the top-right to the bottom-left, with Act VIII made of a single male Individual with oversize penis displaying the standard arms’ posture in the center-bottom (Figure 9). Interestingly enough and based on the recorded superimpositions,

a. Act I, without the twin-headed Individual 29 and Individual 33, was drafted with 3 scenes each including a sexual intercourse episode, with respectively 1, 2, and 3 masks.

b. Act II, overwhelmingly female, features a choreography of dancing characters arranged in a bi-lateral symmetry around a central character (Individual 7) wearing a unique 4-antenna head-gear. The male character Individual 1 and the equidistant “fighting stallions” insert the male principle in this predominantly female episode.

c. Act III, also articulated in 3 scenes emphasizes biological and social reproduction with a farandole of miniature people staged in two parallel rows, emerging from a sexual intercourse episode.

d. Act IV opens the massive entry of masks in the pictorial repertoire.

e. From then on, they became a constant of iconographic syntax crafted in Act V, VI, and VII.

The act features a bi-partition already recorded in Act II with a later addition of a central character displaying a unique arms’ posture. The displayed body language is strikingly different and meaningful, as if assigning equal weight to scene 1 and 2.

The schematization of the drafting style is accentuated from Act IV on, peaking in Act VII. Act VIII at the bottom-center of the composition is made of a single image of a male character with oversize penis, displaying the standard arms’ posture (Figure 9). It is remarkable that he is positioned in a vertical top-bottom axis connecting with the central female character 7 from Act II. In fact, that vertical axis appears to partition the composition into two iterations of the same iconographic narrative: Act I – Act II – Act III on the one hand, and Act IV – Act V – Act VI on the other hand, with Act VII as highly schematic outlier (Figure 9). Iteration 1 features three occurrences of sexual intercourse in Act I and 2 male quadrupeds. It is a predominantly women celebration articulated in two symmetric parts around a central character with two equally symmetric instances of fighting stallions in Act II. And finally, there is a choreographed sexual intercourse leading to the “production of miniature people” in Act III. The emphasis on “society” reproduction with the inserted representation of six animals is plain and unmistakable.

With some variation, Iteration 2 integrates a large number of masks features a predominantly male celebration also articulated on a male central character in Act IV, a display of masks, gender identities, and animals in Act V, and finally, a staged sexual intercourse resulting in the progressive emergence of “miniature people” in Act VI. In this sequence too, the emphasis on “society” reproduction with inserted representations of 5 animals is plain and unmistakable. The structure of Kangjiashimenzi narrative outlined above appears to have been set in place in two main time-sequences. It is above all an allegory on social reproduction, an education board and tool. To be more precise, the locality was very likely used for the performance of the rites of passage from childhood to adulthood for boys and girls. The past is “another country”, with different sensibilities. Nudity, currently ferociously demonized by monotheist religions was not an issue for our remote ancestors. It was a normal part of daily life.

Conclusion

There is a flurry of interpretations of the Kangjiashimenzi petroglyphs, some less empirically grounded than others. Komissarov [4] provide an extensive list of plausible reasons for the existence of the visual representations drafted in that rock-shelter at the foot of the Tianshan range. In so doing, they rightly dismissed all the connotations derived from some contemporary sexual behaviors in the following terms: “the ancient Kangjiashimenzi rock art site is not an example of primitive eroticism but a visual manual on sacred tribal and ancestral rituals [4]. Different parameters of the site have to be taken into consideration to narrow the range of its plausible use and outline the operational modes implemented by Xiaohe people that may have resulted in the creation of the archaeological record at hand. The rock-shelter is located at the foot hill in the southwest flank of the Tianshan range. It is exposed to winter sun, protected from rain, snow, and cold northeastern winds. There is a spring with water flowing nearby and a 2 m thick ash deposit suggest the use of bonfire. No other occupation debris have been reported and there is no documented habitation site in the vicinity. The remoteness of the locality was very likely what made it appealing as a key node of the Xiaohe communities cultural landscape. As suggested almost universally in cultural anthropology initiation events and rituals presiding over the passage from childhood to adulthood for both boys and girls are generally clouded in deep secrecy. Young people are withdrawn from their respective communities, educated and introduced to the secrets of human adult life in secret concealed localities. The performance of these rites of passage generally inserted in a ritual calendar do mobilize an extensive network of communities. The initiates, generally organized in age-sets, live secluded from the communities with their teachers. Bonfires are a crucial element of their daily life in the initiation camp. The iconographic grammar, lexicon, and syntax materialized in the Kangjiashimenzu rock-shelter wall was their pedagogic material, their textbook. Children are taught secrets of adult life and educated to sustain the smooth production and reproduction of the society. Due to its importance in Middle Bronze Age Xiaohe people cultural landscape, many subsidiary events and rituals probably took place at Kangjiashimenzi rock-shelter in the foot hill of the Tianshan range. However, the rite of passage from childhood to adulthood that subsumes almost all the site’s variables and dimensions appears to be the most parsimonious hypothesis.

References

- Wang B (1990) Hutubixian kangjiashimenzi shengzhi chongbai yandiaokehua [王炳华。呼图壁 县康家石门子生殖崇拜岩雕刻画 // 新疆古代民族文化论集]. Engraved petroglyphs with fertility worship in Kangjiashimenzi, Hutubi County. In: Xinjiang gudai minzu wenhua lunji [Collection of papers on the ancient peoples’ cultures of Xinjiang]. Urumqi, Xinjiang daxue chubanshe pp. 35–62 (in Chinese).

- Wang B (2010) Kangjiashimenzi yanhua toulude lishi wenhua xinxi [王炳华。康家石门子岩画 透露的历史文化信息 // 文史知识]. Discovered information about history and culture of Kangjiashimenzi petroglyphs. Wenshi zhishi 2010(2): 14–19 (in Chinese).

- Davis Kimball, JM Behan (2002) Warrior Women: An Archaeologist’s search for History’s hidden heroines. Warner Books, New York.

- Komissarov SA, AI Soloviev, DV Cheremisin (2021) Erotica without Eroticism. Science First Hand 58(2): 88-100.

- Frauenheim E (1998) Ancient Mystery - Jeannine Davis-Kimball investigate the secret of central Asia’s mummy people. The East Bay Monthly 29(3): 1-10.

- O Sullivan R (2017) Landscape and Connections: Petroglyphs of the Altai in the 2nd and 1st Millennium BCE. PhD Dissertation. Merton College, Oxford University, UK.

- O Sullivan R (2018) East Asia Rock Art. In C. Smith, editor, Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology.

- Tang H, G Kumar, J Anni, J Wu, W Liu, et al. (2018) The 2015 Rock Art Mission in China. Rock Art Research 35(1): 25-34.

- Komissarov SA, DV Cheremisin, AI Solovyev (2020) Petroglyphs of Kangjiashimenzi (Xinjiang, P. R. C.): Once again about the chronology and semantics of the site. Vestnik NSU Series: History and Philology 19(10): 9-22.

- Kwang Tzuu C, FT Hiebert (1995) The Late Prehistory of Xinjiang in relation to its neighbors. Journal of World Prehistory 9(2): 243-300.

- Betts A, P Jia, I Abuduresule (2019) A new Hypothesis for early Bronze Age Cultural Diversity in Xinjiang, China. Archaeological research in Asia 17(1): 204-213.

- Betts AVG, M Vicziany, P Jia, AA Di Castro (2019) The Cultures of Ancient Xinjiang, Western China: Crossroads of the Silk Roads. Archaeopress, Oxford, UK.

- Caspari G, A Betts, P Jia (2017) The Bronze Age in the Western Tianshan, China: A new model for determining the seasonal use of sites. Journal of Archaeological Science Report 14(1): 12-20.

- Lijing W, W Yongqiang, L Wenyin, M Spate, K Reheman, et al. (2021) Inner Asian agro-pastoralism as optimal adaptation strategy of Wupu inhabitants (3000-2400 cal BP) in Xinjiang, China. The Holocene 31(2): 203-216.

- Li C, N Chao, E Hagelberg, L Hongjie, Z Yongbin, et al. (2015) Analysis of Ancient Human Mitochondrial DNA from the Xiahe Cemetery: Insights into prehistoric population movements in the Tarim basin, China. BMC Genetics 16(1):78-85.

- Li J , Abuduresule I, Hueber FM, Li W , Hu X , et al. (2013) Buried in sands: environmental analysis at the archaeological site of Xiaohe cemetery, Xinjiang, China. PLoS ONE 8(7): e68957-e68965.

- Librado P, Naveed Khan, Antoine Fages, Mariya A Kusliy, Tomasz Suchan, et al. (2021) The origin and spread of domestic horses from the western Eurasian steppes. Nature 598(7882): 634-640.

- Wenjun W, Manyu Ding, Jacob D Gardner, Yongqiang Wang, Bo Miao, et al. (2021) Ancient Xinjiang mitogenomes reveal intense admixture with high genetic diversity. Science Advances 7(14): eabd6690- eabd6698.

- Zhang Y, M Duowen, K Hu, W Bao, W Li, et al. (2017) Holocene environmental changes around Xiaohe Cemetery and its effects on human occupation, Xinjiang, China. Journal of Geographical Science 27(6): 752-768.

- Trifunov D (2013) Prehistoric Porn created in China 3000 years ago. Global Post.

- Zabiyako AP, W Jianlin (2017) Shitouren Petroglyphs and Phallic images in Rock Art. Religiovedenie 2(1): 12-22.

- Popper K (2002) Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge. Routledge, London/New York.

- Gombrich EH (1995) The Story of Art. Phaidon Press, New York.

- Holl A (1995) Pathways to Elderhood: Research on Past Pastoral Iconography: the Paintings from Tikadiouine (Tassili-n-Ajjer), ORIGINI: XVIII: 69-113.

- Holl AFC (2000) Modes, Temps et Espaces des Images: Les Gravures Rupestres du Dhar Tichitt. Bulletin de l’IFAN Ch. A. Diop 49 (serie B, 1-2): 5-82.

- Holl AFC (2002) Time, Space, and Image Making: Rock Art from the Dhar Tichitt (Mauritania). African Archaeological Review 19(2): 75-118.

- Holl AFC (2006) “This is not an Image, just a Pretext” In Before Farming 2006/2. Online version.

- Holl AFC (2017a) Beyond Shamanism: Dissecting the Paintings from Snake Rock, Namibia. The Journal of Culture 1(1): 27-35.

- Holl AFC (2017b) Here Come the Brides: Reading the Neolithic Paintings from Uan Derbuaen, Tassili-n-Ajjer, (Algeria). Trabajos de Prehistoria 73(2): 211-230.

- Holl AFC (2004a) Saharan Rock Art: Archeology of Tassilian Pastoralist Iconography. Walnut Creek, AltaMira Press pp. 1-178.

- Holl AFC (2004b) Holocene Saharans: An Anthropological Perspective. Continuum Publishing Group, New York/London.

- Holl AFC (2018) Weapons, Tools, and Objects: Material Culture in African Rock Art. In Weapons and Tools in Rock Art: A World Perspective. Edited by AMS Bettencourt, M Santos-Estevez, HA Sampaio. Oxford/Philadelphia, Oxbow Books pp. 23-35.

- Holl AFC, S Dueppen (1999) Iheren I: Research on Tassilian Pastoral Iconography. SAHARA 11(1): 21-34.

- Zhang F, Chao Ning, Ashley Scott, Qiaomei Fu, Rasmus Bjørn, et al. (2021) The Genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim basin mummies. Nature 599(7884): 256-261.

- Qu Y, H Yaowu, R Huiyin, I Abuluresi, W Li, et al. (2018) Diverse lifestyles and populations in the Xiaohe culture of the LopNur region, Xinjiang, China. Archaeological and Anthropological Science 10(1): 2005-2014.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...