Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Review Article(ISSN: 2690-5752)

Formation of the Initial Villages of Gamasiab River Basin (Central Zagros Region, Iran) Volume 6 - Issue 2

Behzad Balmaki*

- Department of Archaeology, Islamic Azad University, Iran

Received:December 15, 2021; Published: January 04, 2022

Corresponding author: Behzad Balmaki, Department of Archaeology, Islamic Azad University (Hamedan Branch), Hamedan, Iran

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2022.06.000234

Abstract

Harsin plain as a characteristic cultural and archaeological area in Central Zagros Region, is an important component of climate Harsin mountain steppe areas, with an average precipitation of 350 to 450 ml. The suitable average annual rainfall and the spacial morphological form of the Harsin plain has provided appropriate condition for establishment of new settlements. Hence, in order to study the cultural evolutions, archaeological survey conducted by the author. During this study, 9 Neolithic site with Initial Villages characteristics of Central Zagros region, identified and surveyed, and some were reviewed. This research show that the Harsin plain< not only has provided some stones needed resources for Neolithic chipped stone industry, but also has provided too broad-spectrum economy by suitable morphological and environmental conditions. In this paper, we introduce some newfound Neolithic sites and analyzing their evidences, and finaly explain the archaeology of Harsin plain and Initial Villages plains in the Central Zagros Region.

Keywords: Archaeology of Harsin Plains; Neolithic; Initial Villages; Central Zagros Region

Introduction

On the basis of archaeological studies, Harsin plain is located in the Central Zagros Region (CZR) and the term “Central Zagros” was first used by the archaeologists who work on the case study of Iran’s prehistorical periods in Canadians and Americans research maps. In topographic maps one camp believe that this area is located in a larger area rather than Kermanshah, Kordestan, Hamedan, Ilam and Lorestan province, But Young considers this area of the center of Kermanshah and Valleys inclined to the other sides [1, Figure 1]. Due to fundamental archaeological factors and the expanded research conducted in this totally archaeological region, it is indicated that this region is the fundamental key of many questions in cultural evolution of human beings, such as several conducted investigations toward the emersion of agriculture and ranching that were commenced in this region. Therefore, the further recognition of this region, especially Harsin plain as a key point of this complex, can be a major help for fundamental questions in case of the cultural evolution of today’s human being. The study of these newly found sites and the results of the scientific excavation at Ganj-Dareh [2- 10] and Sheikhi Abad [11] can be a probe in the process of Neolithic studies of this region.

Climate and Environmental Characteristics of Harsin Region

According to the climate change studies of CZR, we can synchronize today’s climate structure with 10000 years ago records until now [12]. It should be mentioned that the majority of these current changes are driven from changes that are caused by human, erosion, herds and abundant posturing during the current 100 years. The evidence can be the data which are obtained by the climate archaeologists who attempted to explain the environmental feature of this region from Pleistocene up to now. This information are gathered from natural basins of CZR such as Niloufar mirage near Kermanshah, Zaribar Lake in Kordestan and Mir Abad Lake in southern CZR of Lorestan. Based on the information, the type of the region vegetation was drier during the late Pleistocene and then it gradually converted to a more humid region by the early Holocene. Based on the results of these research between the years of 10000 and 6000, after the growth of trees such as oak, pistachio, the region converted into dense woods [13]. Whereas there has been short term drastic changes in the climate of the region from 3000 BC D onwards which definitely effects on the commuting and changes of populations. One of the most accurate information is obtained based on the interpretations and the new sedimentological studies of Zaribar lake sediments with the method of Palaeolimnology and also includes more precise information of climate change [14]. Hence, some of these natural features are mostly considered in this study due to their impact on attracting the residents of aforesaid region in Neolithic period and will be mention as following.

Stratigraphical and geomorphological features of region

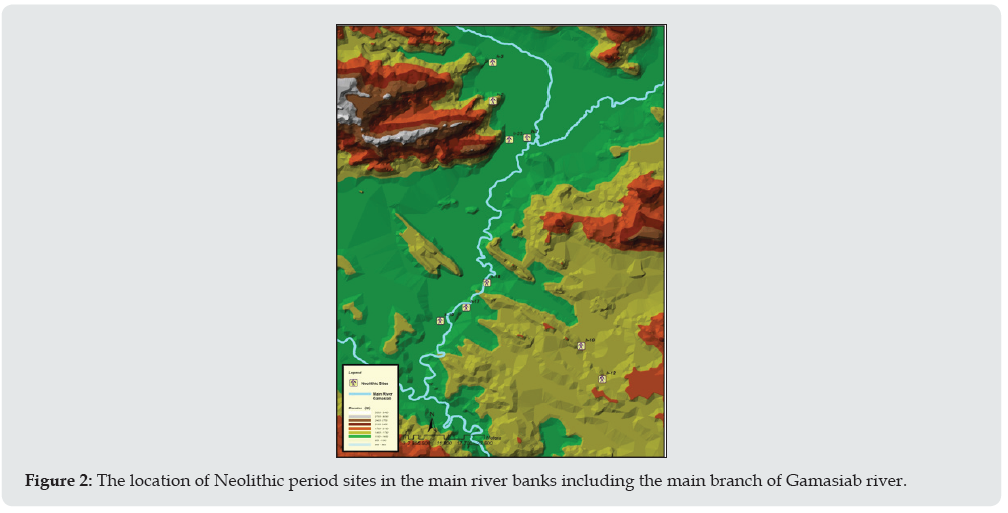

One of the debates of study field of Neolithic period is adjacency to mineral sources and required stones to provide stone tools and meeting basic needs which could be centralized in the place of production or communities would commute by possible ways to provide their required stones. Harsin region is considered as a section of Zagros basement due to its location in the CZR and geomorphology and accordingly the aforesaid region and its mountains were the focus of communities of Neolithic period. Regarding this fact, Zagros basement is the continuance of North, North-east and Arabian Nubian shield which has entered Hejaz from the North-east of Africa and appeared in the western part of this Land and afterwards has gone underneath of the sediments of Eastern Arabia and is placed under the basin of Zagros in the Dezfoul region. The petrological combination of Zagros basement is a crystalline complex of transformed granite and might include Granite, Granodiorite, Granitoid, Schist and probably ophiolite, Marble and other transformed sediments [15]. However, seems that, this morphological structure provides the conditions here for Neolithic settlements (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The location of Neolithic period sites in the main river banks including the main branch of Gamasiab river.

Weather and climate structure

Cold and rainy mountainous areas of Iran plateau is known as favorable mountainous steppes. This part of basin has cold winters with low temperature which is 25°C below zero with cool summers. The precipitations are often in the form of snow, approximately 300 mm, but will reach to 600 mm per year. This part of the basin (mountainous areas of Iran plateau) and the main areas of auriferous form the main source of producing Iran’s plateau water. These areas possess relatively moderate water balance and rich water sources. The most fertile soil resources for formation and evolution, the most suitable plant sources for pasturage and livestock and the most prepared area to produce strategic crops including cereals are all related to this aforesaid steppe area [16]. Therefore, these areas can be considered as a suitable location to start sedentism (Figure 2).

Introducing Initial Villages (Neolithic Sites) in Harsin Region

In the superficial survey of this region between the years of 1386 and 1387 by the author et al, 9 sites possessing findings of Neolithic period were identified. The significant findings of these sites that were possible to identify through surveys in the site, were chipped stone, flake and tools. To produce identification codes sites in the survey, the letter “H” was put at the beginning of each site numbers. Some of the most important sites to be introduced. These sites are as following:

Najoobaran tepe (H-2)

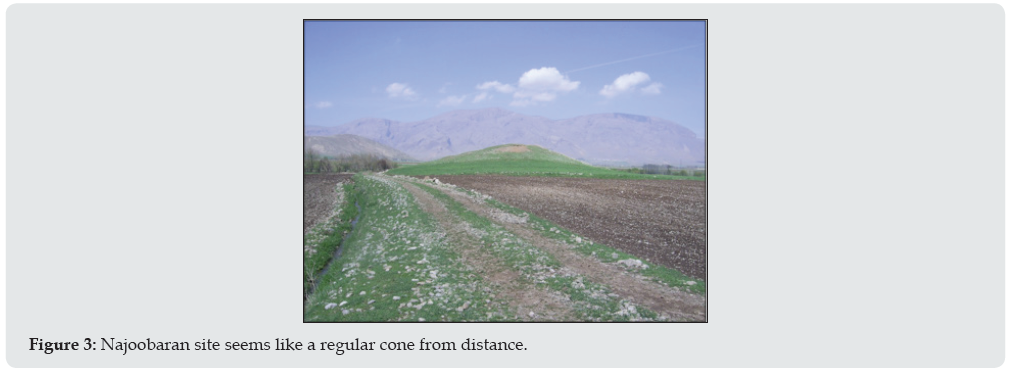

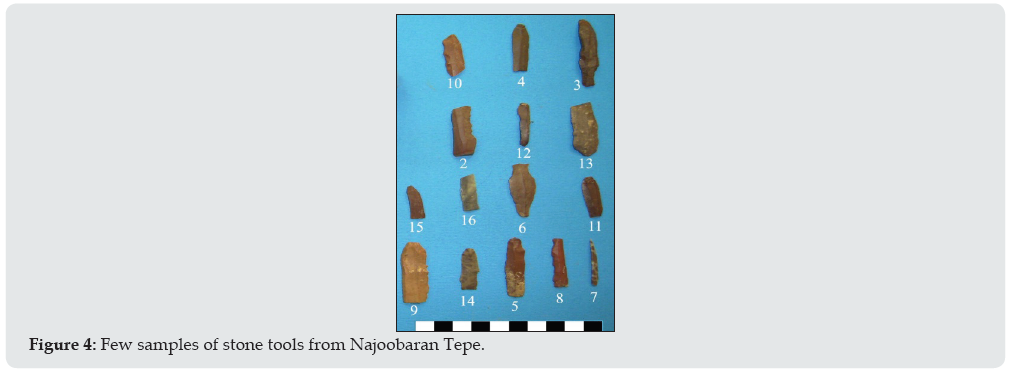

The altitude of this site is 1508 m and is located the eastern side of Najoobaran village. The length and width of this site is 75*90 and its height from the surroundings is 10m. The site attracts attentions with its regular cone shape from distance (Figure 3). Due to the existence of Najoobaran spring as the source of Dinvar river near, this site is turned into a settlement area of Dinvar basin. Here in addition to Neolithic wares, a set of stone tools made of flint were obtained. This set includes Microlith and blades in which the used stone resources are approximately of one type of high quality radiolarites in the color of Brown, light brown and different hues. In this set of 15 tools, 7 has denticulated retouches, notch and retouches made as the result of being utilized and others in the set lack these retouches. In some of the cases, notched retouches are in reverse in surface with microlith shape. Regarding the symmetric edges and the previous removal level, it seems that microlith are produced by pressing method in this site [17,18; Figure 4).

Sohbat Abad Tepe (H-17)

Tepe locates at the height of 1317m above the sea level, in the lands of Gamasiab riverbank and 300m away from Sorkheh-Deh crypt and the western side of Shams-Abad Road. Its dimensions are of 110m length, 70m width and 2/10m height. The tepe is situated in the east of Gamasiab and in front of the great stone mine of Shams Abad. This tepe can be considered as one of the settlement basins of Gamasiab river due to the adjacency of river in 50m. During the excavations conducting in the site, tools such as stone flinders of Neolithic period which were similar to stone tools of Ganj-Dareh and some significant samples of eastern fertile crescent were observed [Figure 5; 18-20].

Figure 5: Some samples of stone tools of Sohbat-Abad site, including flake, chipped stone and flint tools (to compare see: Kozlowski 1994, pp.153-4).

Shams Abad Tepe (H-18)

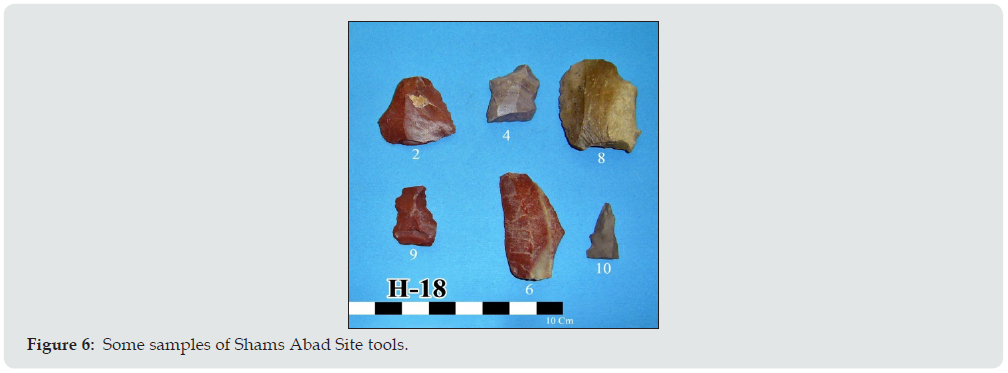

The site locates at the height of 1335m above the sea level, next to Shams Abad village and its dimensions are of 83m length, 73m width and 11m height. The southern side of tepe is surrounded by rural residents and its northern side is embraced by farmlands. due to the situation of Kamish and Gamasiab rivers, this site can be accounted as one of the settlement basins of these rivers. During the excavations conducting in the site, stone tools such as flakes and blade. The stone by which their tools are formed with, is Radiolites and the blade is probably broken y heat. There is also a fully retouched tool and antiquities of erosion apparent on it (Figure 6).

Shad-Abad Sofla Tepe (H-23)

The shad abad Tepe is located at the height of 1451m above the sea level, adjacent to Shad-Abad village with 150m length and 50m width and 20m height above the surrounding lands. By conducting surface survey, a number of stone blade pieces were obtained. three types of radiolites were in the composition of this set. The prevailing type of Radiolites is brown and opaque. Considering technology, the set might be divided in two groups of Flinders (8 pieces) and Blades (2 pieces). The trace of retouching in 4 samples belong to blade. One of the flinders has retouching which is made of using it in one edge and the other finder has connected retouching in addition to hammering trace. One of the blades is retouched in reverse at one end and is similar to a rough drill. There is one regular blade in the aforesaid set which is retouched connectedly in both ends and is cut by the lower end (Figure 7).

Conclusions And Archaeological Analysis of Harsin Plain During Neolithic Period

A part of our knowledge of the Neolithic period of Harsin region is affected by Ganj-Dareh excavations. The famous Ganj-Dareh Tepe is located at the height of 1409m above the sea level, next to Kermanshah-Harsin Road. This site is cone-shaped with 40m diameter and approximate area of 1300 square meters. In 1965, Filip Smith from Montreal University of Canada started to excavate test trenches in the above-mentioned Tepe. By studying the newly found sites introducing in this paper and existing similarities of them due to settlement patterns and approximately similar findings with Ganj-Dareh it can be concluded that such sites had the condition of agriculture and ranching, with the hypothesis that the climate of region had been more humid in early and middle Holocene comparing to now. Based on the conclusions made by the pollenological studies, variant areas of Zagros have transformed into dense woods between years of 10000 and 6000 by increasing the growth of oak and pistachio trees [13].

The average height above the sea level for newly found sites and also Ganj-Dareh Tepe is about 1400. The fact is that, nowadays regions having such height possess an adverse condition in winter and enduring such condition has been difficult for people with lesser experience of settling and could have lead them to live as nomads, whereas archaeological evidence declares another result and pollenological evidence proves the humidity of climate of region in early Holocene. This fact indicates the emersion of changes in climate from early Holocene until now. Though, there exists some instances of keeping livestock in cold seasons including Boz-Mordeh phase (earliest phase), Ali-Kosh in Dehloran plain in which the goats were kept in small cottages 500 years after Ganj Dareh [17]. In this regard and by reviewing the patterns of region settlement of Harsin near Gamasiab, as the main branch, in Harsin plain and based on topographic maps, its location in lower levels of height, are the evidence of existing settling leanings in this plain (Figure. 8).

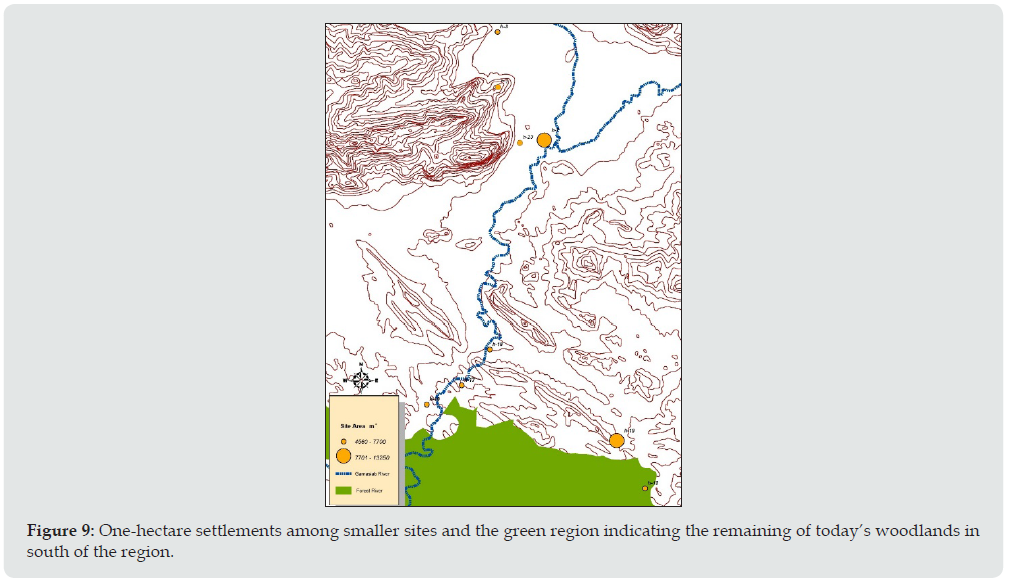

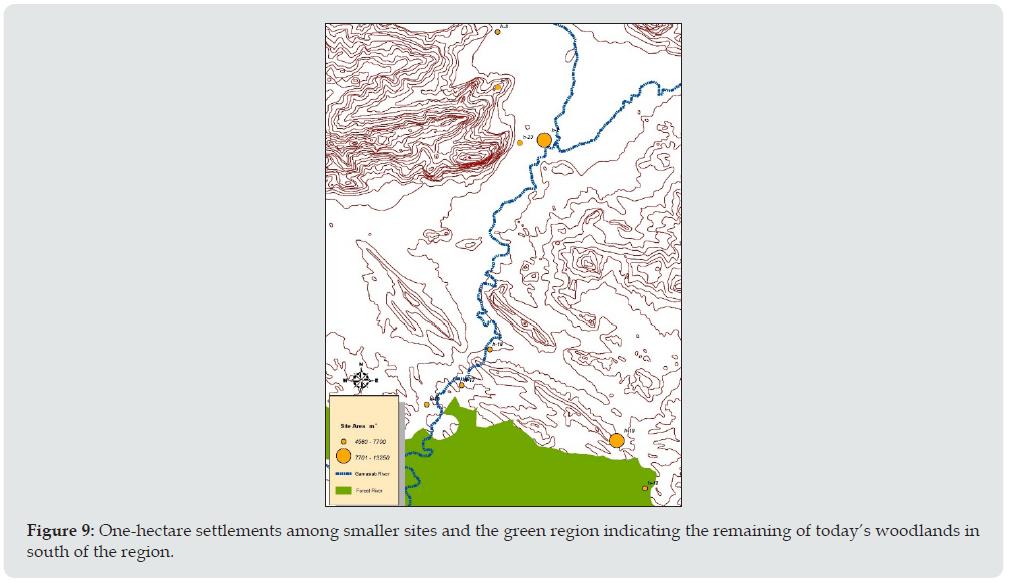

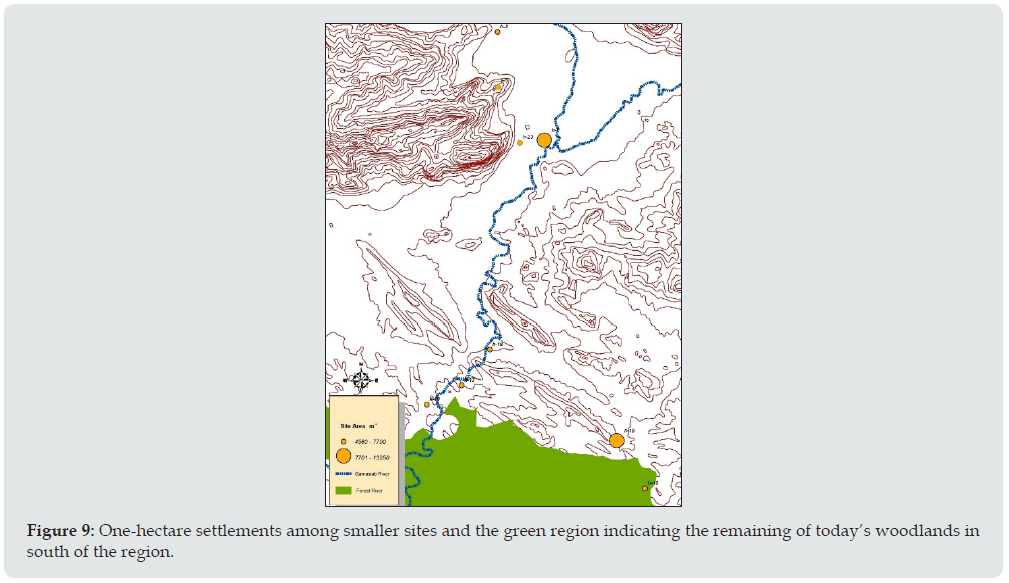

In addition, a twofold living style can be considered for a number of sites including Qal-qeshvand-Vosta site which locate in levels of 1500 and as we review the the extent of this site, we will realize the issue of decreasing the risk of permanent life. The aforesaid site and Ghoozivand region possess the total area of more than 7000 square meters and approximately can be considered as one-hectare sites. The more expansion in these areas can denote the further dominance of people on these regions of even further population Figure 9. In these two areas, the signs of expert and focused production of stone tools in the form of core is observable. Production and dependence of tools means meeting the basic needs permanently besides having a better understanding of Geological conditions of the region. Perhaps in focused studies, we will be able to indicate some signs of trading these expert productions with other smaller surrounding regions. The settlements have achieved the best environmental conditions. Because by regarding the other existing natural phenomena we can count for the following factors: adjacency to woods (even with covering maps), fertile slopes, adjacency to rivers and etc. that can all be move in the event of reaching a vast spectrum of economics, further population and central places.

Figure 9: One-hectare settlements among smaller sites and the green region indicating the remaining of today’s woodlands in south of the region.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the members of the survey team for their kindly cooperation. Grateful thanks to the Cultural Heritage Organization of Kermanshah that provided access to site locations and Dr. Saeedi Harsini from SAMT, Humanities Research Centre, Tehran, Iran.

References

- Young TC (1963) Dalma painted ware. Expedition 5: 38-39.

- Smith P (1967) Ghar-i-Khar and Ganj-I Dareh. Iran 5: 138-9.

- Smith P (1968) Ganj Dareh Tepe. Iran 6: 158-60.

- Smith P (1970) Ganj Dareh Tepe. Iran 8: 178-80.

- Smith P (1972a) Ganj Dareh Tepe, Iran X: 165-68.

- Smith P (1972b) Prehistoric Excavation at Ganj Dareh Tepe in 1967. 5th International Congress of Iranian Art & Archaeology 1: 183-91.

- Smith PEL (1975) Ganj Dareh Tepe. Iran 13: 178-90.

- Smith P (1976) Reflections on four seasons of excavationsat Tapeh Ganj Dareh, in Bagherzadeh F. (ed.) proceedings of the IVth annual symposium on archaeological research in Iran. Iranian Centre for Archaeological Research Tehran 11-22.

- Smith P (1990) Architectural innovation and experimentation at Ganj Dareh, Iran. World Archaeology 21(3): 323-335.

- Mellaart J (1975) The Neolithic of Near East, Thames and Hudson, London, UK.

- Matthews R, Matthews W, Mohammadifar Y (2013) The earliest neolithic of Iran 2008 excavations at Sheikh-e Abad and Jani Central Zagros Archaeological Project, CZAP reports, volume 1, Oxbow books, the british Instituete of persian studies archaeological monographs series IV.

- Stevens LR, Ito E, Schwalb A, Wright JHE (2006) Timing of atmospheric precipitation in the Zagros Mountains inferred from a multi-proxy record from Lake Mirabad, Iran. Quaternary Research 66(3): 494-500.

- Aqrawi AAM (2001) Stratigraphic signatures of climatic change during the Holocene evolution of the Tigris–Euphrates delta, lower Mesopotamia. Global and Planetary Change 28(1-4): 267-283.

- Wasylikowa K, Witkowski A, Walanus A, Hutorowicz A, Alexandrowicz SW, et al (2006) Palaeolimnology of Lake Zeribar, Iran, and its climatic implications. Quaternary Research 66(3): 477-493.

- Giese P, Makris J, Akashe B, Rower P, Letz H, et al (1983) Seismic Crustal Studies in Southern Iran Between the Central Iran and Zagros Belt. In Madelat V (Eds.) Geological Survey of Iran 51: 71-89.

- Qobadian AA (1990) Natural landscape Iranian Plateau, in relation to agricultural uses, conservation, and restoration of natural resources, Tehran, Shahid- Bahonar University of Kerman: (In Persian) p. 12-13.

- Hole F, Flannery KV, Neely JA (1969) Prehistory and Human Ecology of the Deh Luran Plain, Memoir no.1, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Museum of Anthropology.

- Kozolowski SK, Gebel GH (1994) Chipped neolithic Industries at the eastern wing of fertile crescent, In neolithic chipped stone industries of the fertile crescent, proceeding of the first workshop on PPN chipped Lithic Industries, edited By Hans Georg Gebel and Stefan karol Kosolowski, Berlin, ex oriente pp. 143-171.

- Smith P, Young TC, Philip EL (1972) The evolution of early agriculture and culture in greater Mesopotamia implications. by D J Sporer Cambridg Mass: Massa Chuseh Institute of Technology press pp. 1-59.

- Smith P, Mortensen P, Philip EL (1980) Three new early Neolithic sites in western Iran. Current Anthropology 21(4): 511-512.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...