Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Short Communication(ISSN: 2690-5752)

A Finding that Will Take the Anatolian Caravan Routes Back to Much Earlier Times Volume 6 - Issue 2

Haldun Aydıngün and Şengül Aydıngün*

- Department of Archaeology, Kocaeli University, Turkey

Received:November 24, 2021; Published: December 15, 2021

Corresponding author: Şengül Aydıngün, Department of Archaeology, Kocaeli University, Turkey

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2021.06.000232

Short Communication

A small, humble-looking terracotta animal figurine, which is found during the excavations at Can Hasan in south central Anatolia shows the potential of pushing the historical depth of the caravan routes in Anatolia (Turkey) further back in time, to late 5th-early 4th millennium BC. This Paper discusses why and how this figurine may be very important.

Discussion / Archeological Problematic

The oldest incontestable evidence of the use of donkeys as load carriers in Anatolia was provided by the correspondences of Assyrian merchants, which is dated to the first quarter of the 2nd millennium BC. But when reading the correspondences, contracts and other documents of these Assyrian trade colonists one is surprised to find a very mature tradition of “international” trade well comparable to the practices of our time, with its trade laws, courts, commercial contracts, deferred payments and even export insurances provided by special establishments. Such a degree of maturity could only be reached after practising trade for many centuries, or rather many millennia.

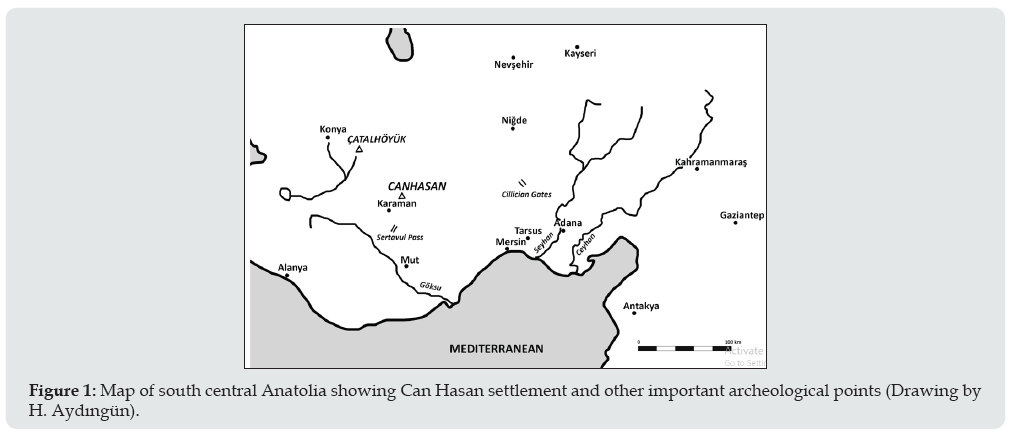

When we try to find out earlier evidence for the existence of such a long distance trade, the earliest we can go back is arguably the 23rd century BC; Naram-Sin of Akkad tells us the victories of his grandfather King Sargon of Akkad in Annatolia, who had organized an expediton upon the requests of Akkadian merchants possibly already resident in Anatolia, they had problems with local rulers. It can be postulated that these merchants probably were working under conditions comparable to those of the Assyrians four centuries later. And also, it can be said that, they were shipping their trade goods from Akkad to mid central Anatolia, much like the Assyrians of the later period, which entails a transportation distance of about 1000 km. In these conditions the use of pack annimals was a must. This leaves us with the existence of a long distance trade in Anatolia seemingly many millenia old but without the evidence for the means of transportation of the goods involved, matching its historical depth (Figures 1-5).

Figure 1: Map of south central Anatolia showing Can Hasan settlement and other important archeological points (Drawing by H. Aydıngün).

Animal domestication in the Near East and its use in transportation

In our popular culture the word “caravan” brings to our minds a series of camels moving in a single row in a desert or some semiarid region. It seems that the words of caravan and camel are bound to be pronounced together. However, camels, oxen and horses were domesticated much later than donkeys, and we learn from Assyrian sources that the oldest caravans in historical record were entirely made up of donkeys [1]. Where and when camel and also horse were fully domesticated and put into the service of humans, are issues still disputed [2]. In this context, the earliest evidence for camel domestication is a terracotta model dated to ca. 2200 BC recovered at Altyn-Depe in west-central Asia, that shows a camel harnessed to a four-wheeled chariot. It is dated to ca. 2200 BC [3]. Around 1500 B.C., people started to benefit from the camel’s extraordinary abilities of carrying large cargos through very harsh environments such as deserts [4]. Marsha Levine [5] states that until the 2000s the place where horse was first domesticated was thought to be Dereivka (4570-3380 BC), an eneolithic settlement established by one of the tributaries of the Dnieper River. But this view is no longer accepted due to many methodological problems. Conclusive evidence of the domestication of horses beyond any doubt comes from the Sintashta-Petrovka culture south of the Ural Mountains, from around 2000 BC. The problem, however, is that the same evidence also shows that horses had already been domesticated here for a very long time [6]. Also coinciding with the same time frame, the peoples who migrated to the Greek peninsula during the 2100-1900 BC period brought fully domesticated horses with them [7].

Around 2500 BC, the Hurrians emerged from the south of the Caucasus Mountains. They established small kingdoms in northern Syria around 1725 BC and are said to have brought horses and light chariots with them from the northern steppes of the Black Sea [8]. Sagona states that horses were not immediately used for pulling heavy carts [9]. Such four-wheeled vehicles generally continued to be pulled by two oxen, and only after the middle of the 2nd millennium BC., we begin to see horses that are harnessed. Thus, it was not until the early 1st millennium BC, that horses took the place of oxen [9]. Donkeys, on the other hand, stand out as the earliest domesticated animals in the Near East and the surrounding regions. According to osteological and genetic studies carried out on finds from early archaeological contexts, donkeys were first domesticated from Nubian wild donkeys in the Chalcolithic Age (around the early 5th or early 4th millennium BC), in northeast Africa (possibly in Egypt) [10]. They became widespread first in Egypt in the 4th millennium BC and spread from there to the Levant. Thanks to the domestication of donkeys, it became possible to transport goods much “cheaper” over difficult lands and over long distances, which consequently reduced the real “prices” of traded goods [10]. For humans, the most basic benefit of donkey has always been its use as a pack or draw animal [10]. In Mesopotamia, evidence from written and iconographic sources shows that from the Sumerian period (approx 2700-2200 BC) onwards donkey was used albeit rarely, to plow fields or carry loads. One of the most important evidence is found on the Standard of Ur, which depicts donkeys pulling a cart [10]. However, the oldest evidence of donkeys’ use as pack animals is a donkey figurine with loads on its back, that is found in southern Levant and dated to the Chalcolithic period [10,11]. Donkeys continued to be depicted mostly as pack animals until the mid-2nd Millennium BC, indicating that they were the most commonly used animal for the transportation of goods in the well-established trade routes of the period [4].

Why is the use of pack animals important?

Trading of goods over very long distances was already a many millennia old practice when the people of Can Hasan created the donkey figurine. It has been determined by neutron activation analyzes that the obsidian of the Melos island in the Aegean Sea had been transported over long distances, especially around the Aegean basin, starting from 10,000 BC. It is also known that in the long time span from the Neolithic period to the Bronze Age, the Spondylus mollusk, which came from the Aegean Sea and was perceived as an important ornament and prestige item, was transported over central Europe as far as France and Germany. Thanks to these two important materials, it is possible to think that trade routes were established in a wide geography covering Europe and the Near East already in very early times [5].

At first one may think that in the Neolithic period people carried their goods within continental Europe commonly through overland routes. But a closer look at the distribution of both obsidian and Spondylus shows that they were generally transported by vessels moving at sea or on rivers. Major rivers such as the Danube, Euphrates, or Nile were like highways crisscrossing the continents. On the other hand, it is obvious that long land routes, without proper river systems were huge obstacles for long distance trading before the advent of the pack animal. However, there are two examples of early long-distance trade that seemingly contradict this argument. Obsidian from Göllüdağ in central Turkey were unearthed at from the PPN-B contexts (7600-6600 BC) of Nahal Lavan, in southern Israel, while those from the Lake Van region in eastern Turkey are similarly found at Ali Kosh in southwest Iran [12]. In a time when there could be no pack animals the distances involved in the transportation of these obsidian objects seems to be a great achievement. But then the quantities of the goods involved put the problem in its correct context; as Cauvin and Chataigner report, the total weight of the 356 pieces of obsidian recovered from Nahal Lavan reaches just a mere 452 gr and those from Ali Kosh totals to 104 gr. This proves to us that before the use of pack animals the trade of any bulky cargo was not possible over the inland routes.

1.1. The Can Hasan animal figurine and its importance

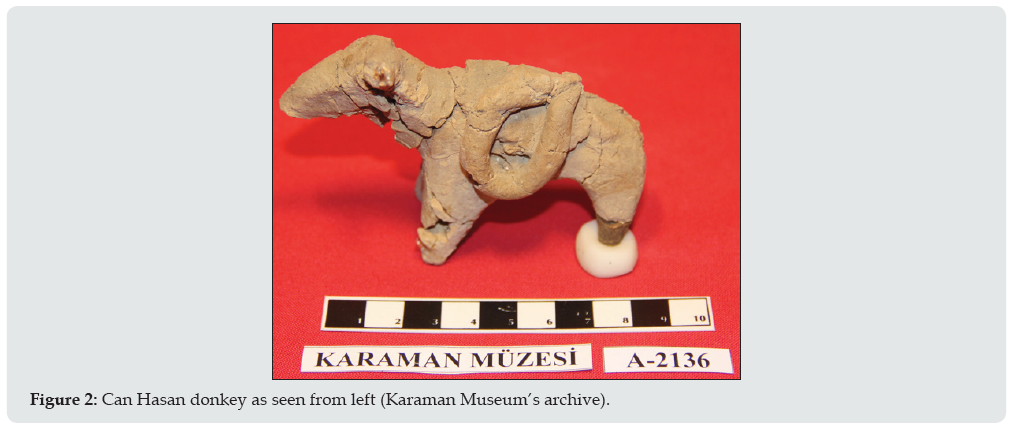

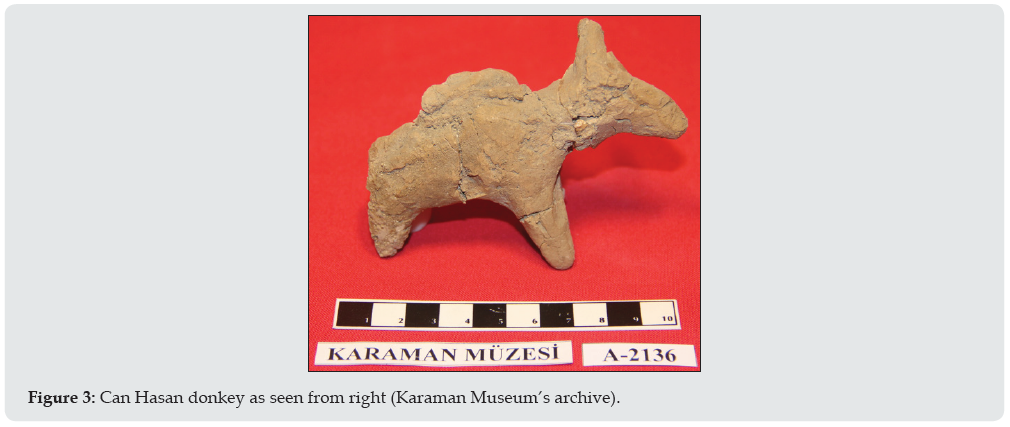

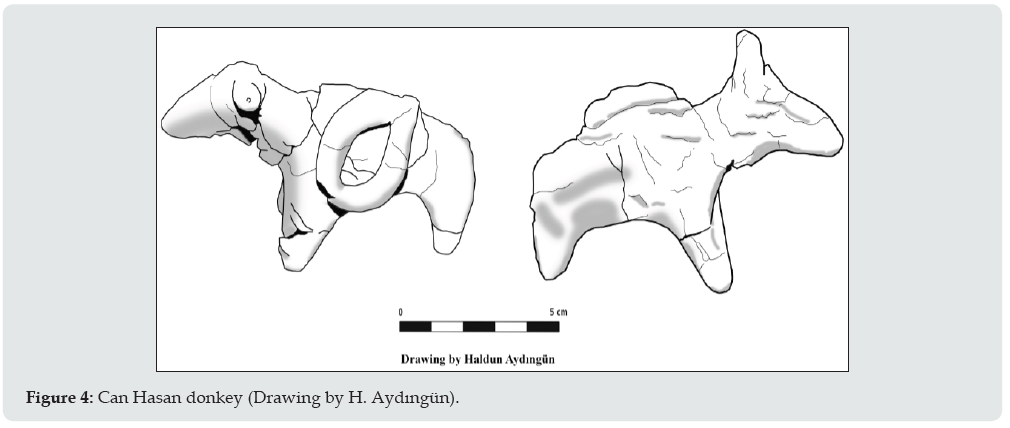

A 7.3 cm long, almost complete animal figurine made of terracotta, was unearthed during the Can Hasan excavations and is currently exhibited in the Karaman museum. The artifact’s inventory number in the museum’s records is 2136 and in the Can Hasan excavation records is CAN66/885. The excavation leader David French dated the figurine to the “Middle Chalcolithic / Late Chalcolithic transition period”. This dating gave us the confidence that we were holding the earliest depiction of any pack animal from Anatolia. David French’s description in his own words is as follows:

a) “One figurine, not quite entirely preserved, represents an animal, presumably domesticated, clearly used as a beast of burden or of agriculture. The upright “horns” could suggest an ox/bovid but, from an alternative point of view, the “horns” could also be interpreted as the prominent ears of a donkey or small equid” [13].

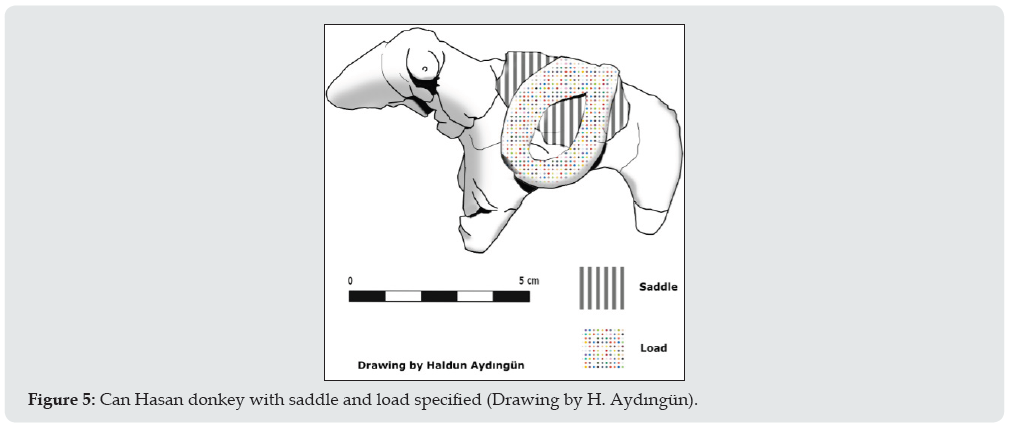

When the figurine was examined, it was seen that the load was not thrown directly on the back of the animal but there was already a primitive saddle under it. Based on this very important detail, it is possible to suggest that at the time of the production of this figurine, the people living in Can Hasan, had experienced in transporting their cargo with animals and they had sufficiently developed the relevant technologies.

Conclusion

In our opinion, the zoomorphic figurine from the Karaman Museum with, inventory number 2136 resembles a donkey the most. Based on our current knowledge It seems that right after donkeys were domesticated in Africa and started to be used to carry loads, this practice reached Anatolia in a surprisingly short time. The figurine stands contemporaneous with the oldest loadbearing donkey depiction from the Chalcolithic period, and thus emerges as the second piece of evidence for the domestication of this animal that is found out of its original region. Here lies one further importance of the figurine; it pushes the earliest possible use of pack annimals in Annatolia almost by two millennia back in time. This is no small feat and brings very important consequences concerning the historical depth of the caravan routes in Anatolia. It also gives us a possible glimpse of the 4th millennium Central Anatolia being on the fringes of the civilized world of Mesopotamia but in relations with it, nevertheless. As quoted above from David French, the excavators of Can Hasan also pointed out the possibility of the figurine depicting a cattle instead of a donkey [13]. This possibility would solve the problem of the almost contemporary appearance of domesticated donkeys in Anatolia and its original place in northeastern Africa. But we think that it looks much more like a donkey with long ears than some cattle with horns. On the other hand, the figurine depicting a bovine, an ox or a donkey would not make much difference because of the existence of the saddle. This small detail in the figurine proves that the people of Can Hasan were using annimals to carry heavy loads in Annatolia as early as 4000 BC.

References

- Larsen M T (1967) Old Assyrian Caravan Procedures. Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten Leiden.

- Heide M (2011) The Domestication of the Camel Biological, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence from Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel and Arabia, and Literary Evidence from the Hebrew Bible. UGARIT-FORSCHUNGEN Internationales Jahrbuch für die Altertumskunde Syrien-Palästinas, Band 42-2010, Ugarit-Verlag, Münster pp. 331-384.

- Kirtcho LB (2009) The Earliest Wheeled Transport in Southwestern Central Asia: New Finds from Altyn-Depe. Archaeology Ethnology and Anthropology of Eurasia 37(1): 25-33.

- Bernstein WJ (2008) Exchange How Trade Shaped the World. Atlantic Monthly Press, New York, USA.

- Séfériades ML (2009) Spondylus and Long-Distance Trade in Prehistoric Europe. The Lost World of Old Europe: The Danube Valley, 5000-3500 BC. Antony D W, Chi J Y (Eds.) Princeton N J, Princeton University Press, Woodstock , USA pp. 178-191.

- Levine MA (2012) Domestication of the Horse. The Oxford Companion to Archaeology, Second Edition. Neil Asher Silberman (Eds.) Oxford University Press, USA p. 15-19.

- Howe T (2014) Domestication and Breeding of Livestock-Horses, Mules, Asses, Cattle, Sheep, Goats, and Swine. The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life. GL Campbell (Eds.) 35: 99-108.

- Brooke JL (2014) Climate Change and the Course of Global History, Cambridge University Press, USA.

- Sagona A (2013) Wagons and Carts of Trans-Caucasus. Tarhan Armağanı - M. Taner Tarhan’a Sunulan Makaleler. Tekin O, Sayar M H, Konyar E (Eds.) İstanbul, Ege Yayınları 277-298.

- Shai I, Greenfield H J, Brown A, Albaz S, Maeir A M (2016) The Importance of the Donkey as a Pack Animal in the Early Bronze Age Southern Levant: A view from Tell es-Safi/Gath, ZDPV (132): 1-25.

- Epstein C (1985) Laden Animal Figurines from the Chalcolithic Period in Palestine. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (258): 53-62.

- Cauvin M C, Chataigner C (1998) Distribution de l'Obsidienne dans les sites arché M.-C. Cauvin A, Gourgaud B, Gratuze N, Arnaud G, Poupeau JL, Poidevin C, Chataigner (Eds.) L'obsidienne au Proche et Moyen Orient, BAR International Series 738, Maison de L'Orient Méditerranéen pp. 325-350.

- French D (2010) Canhasan Sites 3 - Canhasan I: The Small Finds. The British Institute at Ankara.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...