Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2690-5752

Review Article(ISSN: 2690-5752)

Symbolical Approaches of Crocus in the Aegean Bronze Age: A New Proposal for the Crocus Gatherers Fresco from Xeste 3. Volume 8 - Issue 4

Alexandra Tranta*

- Department of Archival, Library and Information Studies, University of West Attica Athens, Greece

Received:March 20, 2024; Published: March 27, 2024

Corresponding author:Alexandra Tranta, Department of Archival, Library and Information Studies, University of West Attica Athens, Greece

DOI: 10.32474/JAAS.2024.09.000310

Abstract

The crocus is a plant with special importance as far as its symbolic character is concerned. Having grouped the depictions of crocus in categories, the present study aims to address its special connection with women (worshipers, priestesses, Pontia) and for the first time it will be supported that the rite shown in the wall painting of the crocus gatherers has four stages and that the landscape depicted is a peak sanctuary.

Shaping the Methodology

The present study concerning the crocus is part of my dissertation thesis, titled “Depictions of floral motifs in the aegean bronze age art” [1]. As it is shown from the title, the main interest concerns the symbolic dimension of the vegetative subjects and their role in the religious iconography of the period under study. Besides the undoubted difficulty of the undertaking [2], we must try “to add words in the book with the images” [3], following a severe methodology and theoretical frame, a process that has been outlined by C. Renfrew in his publication of Phylakopi [4], as there is no civilization that can be understood when cut from its religion [5]. On the basis of the acceptance that the symbols play a main role in the decoding of prehistoric religion [4], the choice that has been made on the material has in itself symbolic character.

The reasonable coherence of the thought and the stages of

reflection can be traced as follows:

1) The definition of the symbolic on the basis of the criterion

of repetition, i.e. the frequent repetition of the symbol and its

correlation. On that basis, we can understand the structural

characteristics of this ritual frame and recognize as having

an equally adorable character all other totals where the same

symbols appear [4-6]. It has to be noted that the correlation

obtains special importance as to other professed charged

motives, i.e. the griffins [7] which in our case have special

interest, because, as we will see below, they help us to define the

central female figure as goddess, accompanied by the demons

[8], the double axe [9].

2) The form of the object which is met and the kind of

imaging, as they do not all serve the same needs and they

are not all made for the same purpose, since certain pottery

categories are considered of special religious importance, i.e.

libation jugs, double vases [10], rhyta [11,12], kymbai [13].

3) After identifying the definition to which presentations,

the floral motifs take a symbolic dimension, I went a step

further and by grouping the common points of the partial

representations I tried to answer the question why certain

categories of people seem to have a closer relation with certain

symbols (as it is put in) [14].

4) Finally, within the frame of the formulation of a theory,

by means of evaluating of the archaeological material [15] as

part of the process of the expression of a proposal for the real

world [16] and on the basis of the prompt of P. Warren to try to

approach the believers of the Bronze Age as people in action

[17], I tried to answer the question that is put as what is actually

done [4]. Therefore, after careful observation of isolated

presentations, these were seen as pieces of a puzzle, as parts

of a total, especially of a rite, which, as has been underlined,

constitutes the marginal zone, that belongs both to the earthly

and to the supernatural world [18]. Adopting the view that

worship has specific stages [4-17], I identify the offering of

flowers as a rite with four stages each suggesting the aim for

which the actions take place within the frame of religion, which

is defined as an act or faith that aims at the satisfaction of a

divine force recognizing in it authority over people’s fate, who

owe faith, obedience and adoration [4].

Discussion: Crocus And Symbolic Correlations

Crocus and its Connection with Women (Worshipers, Priestesses, Potnia).

Gathering the images of crocus, it is noted that specific iconographic correlations appear in many of them. They are classified in a table [19], from which the close relation of plant with female figures, wild goats and apes becomes evident on the basis of the repetition of the correlation. The frescoes of the crocus gatherers (Figure 1) will constitute the core of analysis, because on the one hand this is the most “complete” image, as it includes most of the elements that are mentioned above (the absence of wild goats having no special significance, as the rock landscape is clearly depicted and direct reference to their presence is not necessary) and on the other hand it has been the object of study of many researchers. For these reasons it will constitute a pilot study of the specific fresco, according to which the correlation found in other presentations will be explained. Furthermore, a connection of the crocus with the peak sanctuaries will be suggested and finally the form (i.e. the reason, that is dictating it) in which the crocus gathering belongs will be shown together with the aimed result while it will finally be underlined that the peak sanctuary is presented in the frescoes of the crocus gatherers.

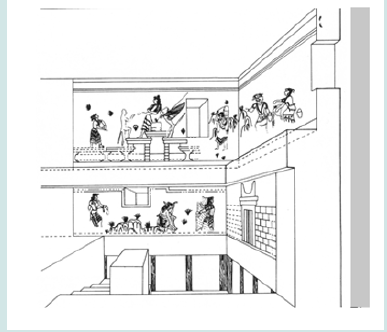

Some years later after the discovery of the frescoes of the crocus gatherers [20], their possible replacement has been proposed, where it is apparent that they constitute two compositions Figure 4 [21]. In the configuration of the east wall the background is a rocky landscape, where crocus grow. An architectural structure is shown, probably an altar or shrine [21]. Three female figures are moving towards that structure. The first figure, the breast of whom is totally uncovered, tends a necklace with beads of crystal. The middle figure, who is shown from the side, is seated and holds her bleeding left foot with her right hand. Her hair is decorated with an olive tree branch and a pin. It has to be noted here that the silver pin used to bind the hair with the decoration of a line of crocus that has been found in the Mavro Spelio of Knossos has on its posterior side the inscription “in order to bind the loose hair I put a pin, I, the high official, the mighty marshal” [22]. Apart from the information on the use of pins as bindings for hair, this element offers a significant witness for the connection of a woman and therefore high priestess with the crocus.

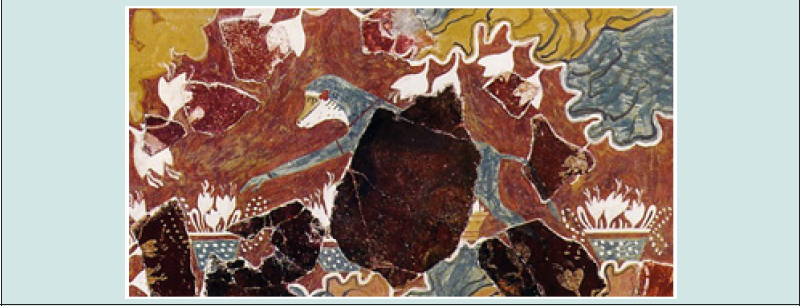

On the North wall, in the center of the representation, an imposingly female figure is seated on a raised scalene construction. She wears impressive jewelry and is flanked by an ape that tends his hand offering to the figure a bouquet of crocus and a griffin. The female figure can certainly be characterized as goddess, as she has a central place in the composition, her scale is higher of that of the others, she stands at a higher level, the offerings come to her and she is flanked by the griffin, the holy protector [7], and the ape (for the role of the apes see) [23]. She has been characterized as the Goddess of Nature [20-30] and yet possibly with a virginal substance, which it is concluded on the basis of the very young age of the girls that are shown to take part in the crocus gathering [31]. The parallelism of the figure with Artemis of the classical years has been underlined as well [31-32]. Behind the ape another female figure empties crocus from her basket in another bigger basket. The baskets, according to a certain point of view, had typical dimensions i.e. they contained the same number of flowers, so that the standardization of the production could be possible [33]. Let’s remember that additional indications of crocus offerings to a goddess are the dress plaques from faience (figure 2) from the Temple Repository [3, 5,34].

The correlation of the ape with crocus is very intense in the crocus gatherer fresco (figure 3), a representation that has been explained as a spectacular demonstration of holy apes related to the celebrations for the honor of the goddess [35]. This is shown by the fact that the gardens did not have simple decorative significance, but constituted areas, where the presence of the goddess was noticeable [36]. With their presence on frescoes, it is considered that the apes are shown to undertake worship activities for the honor of the goddess [37] whereas the view that this is a symbolic representation in the sphere of imagination, is not necessarily against the first.

The crocus is considered as a flower suitable for gathering and offering to the goddess or her representative: N. Marinatos says that the crocus gatherer cuts the crocus in order to offer them to the Goddess. The flowers of crocus, apart from being the sole objects of offer, were possibly also used for the making of garlands, as shown from the fresco of garlands [38] and attests the dance in Oedipus epi Kolono: «the golden blond crocus for our two big Goddesses old garland» (692-683). These elements deny the view that crocus is not suitable for garland [39]. Therefore, it seems possible that crocus was used for the fabrication of perfumes or cosmetics made from its oil aiming to become an offering to the goddess [28]. It is possible that crocus was used in perfumery, as the decoration of small as koi with crocus testifies [40] and possibly declares its presence in the fresco of the young priestess from Akrotiri, if the substance that is in the incense burner that the figure holds is crocus, as it has been proposed [21,41-42].

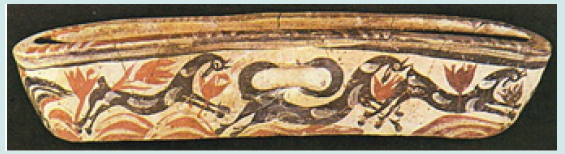

The symbolic character of the crocus is confirmed by its presence in special categories of pottery, as strainers, rhyta, kymbai (Figure 4), double vases, and a clay table of offerings [20]. The presence of crocus on them indicates that “an examination of the ceramic material shows that the crocus (and the pendant-petal motif)... not only can be linked with sanctuaries and cult but that these motifs were chosen for vessels intended to be used for ritual purposes” [43].

Apart from the fact that the pictures present only some moments of the celebration, leaving outside the events that took place before and after and a wide net of similar beliefs and symbolisms [25], the fresco of the crocus gatherers is one of the cases where there is an agreement among researchers that the ritual of initiation is presented. N Marinatos considers the fresco as the presentation of a ritual that aimed to prepare the young girls for the duties of women. Consequently, the presentation of blood aimed at the familiarization of women with it during menstruation and childbearing [37]. S. Immerwahr says that the artist tried to give the image of young women that are concerned with a transition ritual that took place at the borderline from adolescence to the adulthood [44]. E. Davis, judging from the four different types of hairstyle of the girls, suggested that the frescoes from Xeste 3 present the women in four stages of age-initiation with the basic differences of hairstyle [31]. P. Rehak says that within Xeste 3, crocus is a verifying theme that establishes a connection between the goddess and women of all ages, from prepubescence through adulthood [34]. According to anthropological elements the initiation starts with the changes of hairstyle and Chr. Doumas comments that when the hair is totally cut it could mean the first stage of initiation, whereas the partial cut is a more advanced step [45]. In the fresco of the crocus gatherers, the gathering of crocus may possibly be a process, a real fact that took place every autumn. N. Marinatos supports that a real performance and a real construction are depicted [13].

It has been noted that the “gathering of crocus-a very important activity for the economy of the community- takes the dimension of a religious celebration, exclusively for women, with all the relevant solemnity, which is a presumption based on the rich clothing and jewellery of the mature women and the young girls with their fancy hairstyling...” [46]. These characteristics (luxurious clothes, rich decoration, jewellery, fancy hairstyling) declare a high social class. According to one view the luxurious clothes of the women are the best clothing in order to celebrate the Goddess of Nature, and challenge her epiphany [47]. Here it has to be noted that the clothes of the young girls, especially the fine cloth, are decorated with designs that present crocus [48,49]. The correlation of the crocus with women that belonged to a high social class has been noted [14]. N. Marinatos says that it is a “mixture of the real and the imaginary”, an image at two levels, the real and the symbolic [18], whereas the offer of flowers to the goddess takes us to an unreal landscape [21]. It may be the representation of a real fact, the gathering of crocus at Thera, that ended with the symbolic offer of the product, which was precious for the island, to a goddess of nature [29].

Reviewing: during the crocus gathering, a product that was

significant for the island’s economy, the young women (probably

within the framework of an initiation ritual) dedicated a part

of their crop to the goddess of nature, in order that she would

return fertility to them. It is an offer for a good crop, aiming at the

expression of gratitude and reward of the people for the autumn

regeneration of nature after the summer drought. This act meets the

nature of Minoan religion, that has been characterized as a fertility

religion (Peatfield 1994, 227). Accordingly, the sole moments of the

celebration that are presented in the representation of the Crocus

gatherers can be put in the following outline:

1) Appeal to the goddess as a result of the visit of the adorers

(or priestesses) to the peak sanctuary.

2) The epiphany of the goddess as a responce to their

invitation.

3) Offer of crocus to the goddess.

4) Return of the goddess with rain/fertility.

What we have to do is to define that the place where the offer of crocus is made is a peak sanctuary.

The crocus and its connection to the peak sanctuary

The peak sanctuaries are considered to be the places where

the celestial goddesses, who affected the weather phenomena and

caused rain [50], were worshiped. Therefore, the rain, which is

considered the presupposition of fertility, is related to the fertility

of women, because as I have supported elsewhere, the fertility of

the earth is related to that of women [51]. This is very important of

the women with the crocus in this case, since for the first time an

answer is given to the question why certain symbols are related to

certain special human categories [14]. So, the botanic properties of

the plant (the fact that it blooms during the autumn in rocky places)

and its multiple uses in dyeing and pharmaceuticals (especially

its medicinal role against dysmenorrhea) constitute the starting

point for its association with the world of women, its correlation

with them and its operation as a symbol. Accordingly, once again

the decorative and symbolic characters co-exist. On the basis of

the representation of the peak sanctuary from Zakro [52] and the

excavation elements, three elements contribute to the recognition

of the peak sanctuary [53].

1) The rocky height is established in an area of evergreen

flora. Apart from the representation of the rocks in the rhyto

and the confirmation of the places by the excavation elements,

the rocky landscape is highlighted even more by the names

of the places of the peak sanctuaries: St. Alexiou explained

etymologically the name Petsofas as the rocky place, where

all those who came damaged the soles of their shoes [54].

Accordingly, the presence of wild goats in the rhyto of Zakros

witnesses the rocky place, as well as the name of the Traostalos

place, i.e. the stable of the goats, where a peak sanctuary is

found [55].

2) The scalene construction. At Mt. Jouktas, the arrangement

of the rooms is scalable both themselves among them and in

relation to the rest following the natural formation of the rock

[56].

3) The characteristic findings, mainly human figurines and

figurines of animals and votive offerings representing various

separate parts of the body.

Conclusion

Let’s see examine the relation of our representation to the above characteristics. The parallelism between Minoan Crete and Akrotiri is not strange since, as it has been proved, religious elements coming from the Minoan Crete are present at Akrotiri [13,37]. Additionally, Akrotiri shows rocky topography suitable for the existence of a peak sanctuary. The crocus is often present in rocky landscape. This has its starting point the botanical property of the plant to grow at rocky places and decorate rocky gardens. Apart from the representation of rocks at the crocus gatherer and the crocus gatherers frescoes, the rocky landscape is considered to be presented at the fresco of apes playing the lyre and holding a sword (cat. no 9) [20,44]. Goats are presented in the fresco in the wild goats that flank the olive tree, which is reference to the adoration of nature [44], and the kymbai [57]. Goats and wild cats are presented at the fresco from Ayia Triada, which has been characterized as symbolic. At this fresco, the correlation of the animals with the rocky ground may refer even indirectly to ritual scenes, while it can possibly be explained as peak sanctuary [14]. Additionally, the crocuses on the dress plaques from the Temple Repository aim to represent a peak sanctuary [44]. Finally, the possibility that the animals that are attributed to another fresco form Akrotiri are goats constitutes a significant element as S. Immerwahr considers that in that fresco a peak sanctuary is shown [44]. Yet, the epiphany of the goddess is realized in an outdoor place [44] whereas the peak sanctuary is considered the most suitable place for the goddess’s epiphany [53].

Certain remarks reinforce this supposition. If we accept that the goddess who is worshiped at the peak sanctuaries has rainmaker character, the crocus, as an especially autumnal flower is the most suitable offering after a summer drought. Additionally, the property of the plant to grow in rocky ground meets completely with the topography of the peak sanctuaries that, as we have seen above, are established in rocky places. Let’s remember as well that fruits as offering to the goddess were contained in the basket that appears placed at the peak sanctuary in the rhyto from Knossos [54,58].

Attention must be paid to the scalene construction in which the goddess is seated in the crocus gatherers fresco. As it has been noted, the height is a necessary element for the declaration of the divine epiphany [59]. This reminds one of the main characteristics of the peak sanctuary, which is the scalar construction.

One more element, reinforcing our position, is that the representations we refer to, come from the Middle Minoan III/ Late Minoan I, during which the peak sanctuaries flourish. We must remember here that most crocus representations appear during these periods.

Consequently, the first two characteristics (the topography and the scalar construction as well as the time) apply in the case of the crocus gatherer’s fresco of the peak sanctuaries. But what happens with the absence of figurines from the imaging? This cannot reverse our correlation for the following reasons: First, figurines are not found at Akrotiri as it is noted [37]. Consequently, this may be is a local peculiarity. Second, if we accept the view that the figurines represent the worshipers, their absence is not strange because the worshipers themselves are shown in the fresco. Third and most importantly: according to a recently expressed view, the statuettes at the peak sanctuaries are parallelled to the three-dimensional versions of the worshipers as participants of the rituals [60]. Therefore, since we are talking about fresco with the representation of certain moments, as we saw earlier, the represented worshipers play their role, and yet their absence is expected. Concluding, on the basis of the elements that are mentioned above [61-62], we support the view that at the fresco of the crocus gatherers moments of an offering ritual are represented in four stages and that the peak sanctuary constitutes its background.

References

- Τράντα Νικόλη Α (2007) Η φυτική διακόσμηση των προϊστορικών χρόνων. Διδακτορική διατριβή. Πανεπιστήμιο Ιωαννίνων, Τμήμα Ιστορίας και Αρχαιολογίας.

- Hawkes C (1954) Archaeological theory and method: Some suggestions of the Old World. American Anthropologist 56(2): 155-168.

- Nilsson M P (1950) The Minoan-Mycenaean religion and its survival in Greek religion, 2nd edition, Lund 22(4): 429-431.

- Renfrew C (1985) The archaeology of cult. The sanctuary at Phylakopi. Annual of the British School at Athens 18.

- Marinatos N Hägg R (1983) Anthropomorphic cult images in Minoan Crete. In O. Κrzyskowska and L. Nixon (eds.), Minoan Society. Proceedings of the Cambridge Colloquium pp: 185-201.

- Moore A D Taylour W D (1999) The temple complex, Well Built Mycenae fasc. 10.

- Tζαβέλλα Εvjen X (1970) Tα πτερωτά όντα της προϊστορικής εποχής του Αιγαίου, Αθήναι.

- Weingarten J (2000) The transformation οf Egyptian Taweret into the Minoan Genius. In Α. Καρέτσου and Μ. Ανδρεαδάκη- Βλαζάκη (eds.), Κρήτη-Αίγυπτος. Πολιτιστικοί δεσμοί τριών χιλιετιών, Μελέτες, Αθήνα 114-117.

- Νικολαΐδου Μ (1994) Ο διπλός πέλεκυς στην εικονογραφία των μινωικών σκευών. Προσεγγίσεις στη δυναμική του μινωικού θρησκευτικού συμβολισμού, αδημοσίευτη Διδακτορική Διατριβή, Θεσσαλονίκη.

- Καραγιάννη Ε (1984) Μινωικά Σύνθετα Σκεύη (Κέρνοι;), αδημοσίευτη Διδακτορική Διατριβή, Αθήνα.

- Koehl R B (1980) The functions of Aegean Bronze Age rhyta. In R. Hägg and N. Marinatos (eds.), Sanctuaries and Cults in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the First International Symposium at the Swedish Institute in Athens pp: 179-188.

- Koehl R B (1990) The rhyta from Akrotiri and some preliminary observations on their functions in selected contexts. In D.A. Hardy- C.G. Doumas- J.A. Sakellarakis- P.M. Warren (eds.), Thera and the Aegean World III. Proceedings of the Third International Congress, Santorini, Greece pp: 350-362.

- Marinatos Ν (1990) Minoan-Cycladic syncretism. In D.A. Hardy- C.G. Doumas- J.A. Sakellarakis- P.M. Warren (eds.), Thera and the Aegean World III. Proceedings of the Third International Congress, Santorini, Greece, 3-9 September 1989, London 370-377.

- Evely D (1999) Fresco: A Passport to the Past. Minoan Crete through the Eyes of Mark Cameron, Athens.

- Peatfield A (2011) Water, fertility, and purification in Minoan religion. In Klados: Essays in Honour of J.N. Coldstream, Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 40(63): 217-227.

- Clarke D (1968) Analytical Archaeology, London.

- Warren P (1988) Minoan religion as ritual action, Gothenburg.

- Marinatos N (1985) The function and interpretation of the Theran frescoes. In L’ Iconographie Minoenne. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique pp: 219-230.

- Angelopoulou Ν (2000) Nature scenes: An approach to a symbolic art. In S. Sherratt (ed.), The Wall Paintings of Thera. Proceedings of the First International Symposium, Petros M. Nomikos Conference Centre, 30 August- 4 September 1997, Athens, 545-554.

- Marinatos S (1976) Excavations at Thera VII, Athens.

- Marinatos Ν (1984) Art and religion at Thera. Reconstructing a Bronze Age society, Athens.

- Davis S (1973) The Minoan silver pin from Mavro Spelio: An interpretation.

- Vanschoonwinkel J (1990) Animal representations in Theran and other Aegean Arts. In D.A. Hardy- C.G. Doumas- J.A. Sakellarakis- P.M. Warren (eds.), Thera and the Aegean World III. Proceedings of the Third International Congress 327-347.

- Morgan L (1988) The miniature wall paintings of Thera, Cambridge.

- Μπουλώτης Χ (1995) Αιγαιακές τοιχογραφίες. Αρχαιολογία και Τέχνες 55: 13-32.

- Ντούμας Χ Γ (1987) Η Ξεστή 3 και οι κυανοκέφαλοι στην τέχνη της Θήρας. Ιn Ειλαπίνη. Τόμος Τιμητικός για τον Καθηγητή Νικόλαο Πλάτωνα, Ηράκλειο pp: 151-159.

- Ντούμας Χ (1992) Οι τοιχογραφίες της Θήρας, Αθήνα.

- Peterson S E (1982) Wall-paintings in the Aegean Bronze Age: the procession frescoes, Ph.D. Thesis, Minnesota p. 1-24.

- Amigues S (1988) Le crocus et le saffran sur une fresque de Thera. Revue Archéologique, 227-242.

- Goodison L (1989) Death, Women and the Sun, London.

- Davis E N (1986) Youth and Age in the Thera Frescoes. American Journal of Archaeology 90(4) 399-406.

- Marinatos N (1987) An offering of saffron to the Minoan Goddess of Nature. The role of the monkey and the importance of saffron. In T. Linders and G. Nordquist (eds.), Gifts to the Gods. Proceedings of the Uppsala Symposium 1985.

- Sarpaki A (2000) Plants chosen to be depicted on Theran wall paintings: Tentative interpretations. In S. Sherratt (ed.), The Wall Paintings of Thera. Proceedings of the First International Symposium, Petros M. Nomikos Conference Centre, 30 August- 4 September 1997, Athens 657-680.

- Rehak P (2004) Crocus costumes in Aegean art. In A. Chapin (ed.), Χάρις. Essays in honor of Sara A. Immerwahr, Hesperia 33(1): 85-100.

- Πλάτων Ν (1947) Συμβολή εις την μελέτην της μινωικής τοιχογραφίας: Ο κροκοσυλλέκτης πίθηκος. Κρητικά Χρονικά 1: 505-524.

- Πλάτων Ε (1987) Ελεφάντινα πλακίδια από το Ανατολικό Κτήριο στη Ζάκρο. In Ειλαπίνη. Τόμος Τιμητικός για τον Καθηγητή Νικόλαο Πλάτωνα, Ηράκλειο 209-226.

- Marinatos N (1984) Minoan Threskeiocracy on Thera. In R. Hägg and N. Marinatos (eds.), The Minoan Thalassocracy. Myth and Reality. Proceedings of the Third International Symposium at the Swedish Institute in Athens, 10-16 June 1982, Stockholm, 167-178.

- Warren P (1985) The fresco of the garlands. In L’ Iconographie Minoenne. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 11(1): 187-207.

- Hiller S (2000) Thera Ships Egypt and Homer. In S. Sherratt (ed.), The Wall Paintings of Thera. Proceedings of the First International Symposium, Petros M. Nomikos Conference Centre Athens pp: 334-343.

- Porter R (2000) The flora of the Theran wall pintings: Living plants and motifs-sea lily, crocus, iris and ivy. In S. Sherratt (ed.), The Wall Paintings of Thera. Proceedings of the First International Symposium, Petros M. Nomikos Conference Centre, 30 August- 4 September 1997, Athens 603-630.

- Marinatos S (1972) Excavations at Thera V, Athens.

- Morgan L (1988) The miniature wall paintings of Thera, Cambridge.

- Walberg G (1988) Problems in the interpretation of some Minoan and Mycenaean cult symbols. In E.B. French and K A Wardle (eds.), Problems in Greek Prehistory. Papers presented at the Centenary Conference of the British School of Archaeology at Athens 211-218.

- Immerwahr S A (1990) Aegean painting in the Bronze Age, Pennsylvania pp: 1-305.

- Ντούμας Χ Γ (1987) Η Ξεστή 3 και οι κυανοκέφαλοι στην τέχνη της Θήρας. Ιn Ειλαπίνη. Τόμος Τιμητικός για τον Καθηγητή Νικόλαο Πλάτωνα, Ηράκλειο pp: 151-159.

- Μπουλώτης Χ (1995) Αιγαιακές τοιχογραφίες. Αρχαιολογία και Τέχνες 55: 13-32.

- Immerwahr S A (1983) The People in the frescoes. In O. Κrzyskowska and L. Nixon (eds.), Minoan Society. Proceedings of the Cambridge Colloquium 1981, Bristol, 143-153.

- Τελεβάντου Χ (1982) H γυναικεία ενδυμασία στην προϊστορική Θήρα, Αρχαιολογική Εφημερίς 113-135.

- Tζαχίλη Ι (1997) Υφαντική και υφάντρες στο προϊστορικό Αιγαίο 2000-1100 π.Χ., Ηράκλειο.

- Rutkowski B (1986) The Cult Places of the Aegean, New Haven and London.

- Τράντα Νικόλη Α (2003) Η σημασία του φοίνικα στην Κρητομυκηναϊκή θρησκεία: μία νέα Προσέγγιση. Αρχαιολογία και Τέχνες 88: 80-85.

- Πλάτων Ν (1974) Ζάκρος Το νέον μινωικόν ανάκτορον, Αθήναι.

- Peatfield A A D (1990) Minoan peak sanctuaries: History and society. Opuscula Atheniensia 18(8): 117-131.

- Πλάτων Ν (1951) Το ιερόν Μαζά (Καλού Χωριού Πεδιάδος) και τα μινωικά ιερά κορυφής. Κρητικά Χρονικά (5): 96-160.

- Chryssoulaki S (2002) The Traostalos peak sanctuary: Aspects of spatial organization. Aegaeum 22: 57-65.

- Ιωαννίδου Καρέτσου Α (1976) Το Ιερό Κορυφής Γιούχτα. Πρακτικά της Αρχαιολογικής Εταιρείας, 408-418.

- Marinatos S (1974) Excavations at Thera VI, Athens.

- Αλεξίου, Στ (1959) Νέα παράστασις λατρείας επί μινωικού αναγλύφου αγγείου. Κρητικά Χρονικά 13: 346-352.

- Hägg R (1983) Epiphany in Minoan Ritual. Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, vol. 30, 184-85.

- Peatfield A (2002) Divinity and performance on Minoan peak sanctuaries. Aegaeum, vol. 22, 51-55.

- Day J (2011) CROCUSES IN CONTEXT: A Diachronic Survey of the Crocus Motif in the Aegean Bronze Age. Hesperia: The Journal of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens 80(3): 337-379.

- Shaw J W (1978) Evidence for the Minoan tripartite shrine. American Journal of Archaeology 74: 429-448.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...