Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1687

Review Article(ISSN: 2641-1687)

Simplified Analysis of Cystometrogram of Urinary Bladder in Terms of Elasticity and Plasticity Volume 4 - Issue 3

Wim A van Duyl*

- Formerly at Department of Medical Physics and Technology Erasmus University Rotterdam and Department of Electronic Instrumentation WTechnical University Delft, Netherlands

Received: April 26, 2023; Published: April 28, 2023

Corresponding author: W.A. van Duyl, Formerly at Department of Medical Physics and Technology Erasmus University Rotterdam and Department of Electronic Instrumentation Technical University Delft, Netherlands

DOI: 10.32474/JUNS.2023.04.000187

Abstract

A mechanical analysis is given of main part of a slow-filling cystometrogram having a constant steepness, corresponding to a constant cystometrographic compliance C. Present analysis is, in contrast to earlier published analysis, based on the combination of variable elastic and variable plastic elongation of bladder wall, characterized by elasticity parameter E and plasticity parameter P, both dependent on the elongated state of bladder wall. A constant compliance C is explained by similarity of the non-linear dependencies of E and P on elongation and coupled via similarity constant F. A constant compliance C is ascribed to a constant F, independent of C. F determines the ratio between elastic volume VE and rest volume VR. VE and VR as parts of total volume V have different meanings for bladder function. Factor F depends on recent strain and contraction history of the bladder and changes by spontaneous contraction activity. The mechanical model and analysis are related to a network of actomyosin units representing the contractile structure of bladder smooth muscle.

Keywords: Urinary bladder; cystometrogram; analysis; compliance; elasticity; plasticity

Introduction

During physiological filling of the bladder and during clinical slow filling cystometry (<1 ml/s) tonic detrusor pressure pdt is low and the graph pdt versus volume V, clinically known as the cystometrogram, has in the range of V from 50 to 400 ml a small almost linear upwards slope with pdt in the range of e.g., from 5 to10 cm H2O (Figure 1). In the past the remarkable property of the bladder to store volume within a large range in combination at low almost constant pressure was ascribed to active neurogenic control of the muscular bladder wall [1,2]. According to publications of Remington [3], Alexander [4] and Mastrigt et al [5] the pseudostatic volume-pressure relation of passive, not-activated bladder is ascribed mainly to the passive property of elasticity. Nevertheless, the description of the bladder by passive properties of bladder wall needs to imply the muscular component that potentially has active properties. The activated state of the muscular tissue component may affect the passive properties. The ratio of a volume change (ΔV) and associated change in tonic detrusor pressure (Δpd) is defined by ICS-Standardizing Committee [6] as compliance C: C = ΔV/Δpd. Steepness of the cystometrogram Δpd/ΔV=1/C. In slow filling cystometry bladder compliance is evaluated as a clinical parameter to judge the reservoir function of the bladder. Different clinical methods of determining compliance are published, yielding different ranges of values for normal and abnormal compliance [7].

Here we take for the normal values of compliance in human 20-40 ml/cm H2O. A bladder with low compliance is diagnosed as hypertonic and with high compliance as hypotonic. Increase of volume V of the bladder from 50 ml to 400 ml is accompanied by considerable elongation of circumference of approximately 200%. For a bladder assumed to be an elastic organ this elongation is fully elastic. In mechanics relative elastic elongations are related to stress. Nowadays, besides elasticity also viscosity and plasticity are considered as properties of bladder tissue which contribute significantly to the relation between bladder volume V and tonic pressure pdt. These properties are more or less homogeneously distributed in bladder tissue and can been expressed in a mechanical model composed of separate elements, each representing a basic mechanical property lumped in a specific discrete element. The pseudo-static elongated state of bladder wall during slow filling is coupled to stress in the wall. In present approach the elongated state is ascribed to distributed elastic elongation and distributed plastic elongation of bladder tissue. The elastic elongation is completely recovered when stress in the wall is zero again. In contrast to elastic elongation, the attained plastic elongated state is maintained when stress returns to zero. More plastic elongation is obtained only when the applied stress is higher than a certain threshold value.

The level of this threshold is set by previous maximum stress; the higher previously stress the higher is the threshold level to be passed to get a more plastic elongated state. Thanks to this threshold phenomenon of plasticity a plastic elongated state resists static stress equal to or below the threshold value without elongation. Hence a model consisting of an arrangement of an elastic element in series with a plastic element can represent the property of the bladder wall to maintain a certain elongated state while it encloses a certain volume V at a certain static pressure pdt. In the following a simplified mechanical analysis is given of the course of pseudo-static cystometrograms taking account of plasticity of bladder tissue. This means that, in contrast to a fully elastic bladder model, the considerable relative elongation of bladder wall during filling is not only ascribed to elastic elongation but also to additive plastic elongation. Time dependent visco-elastic behavior of bladder tissue is not considered here. The plastic elongated state of the bladder determines bladder volume enclosed with zero pressure. This volume can be determined by emptying actual bladder volume with that part needed to attain just zero pressure.

This remaining part is called rest volume VR .The volume needed to be withdrawn to reduce pressure to zero is that part of actual total bladder volume V that causes elastic elongation of the wall and is called elastic volume VE. Hence, we distinguish in total bladder volume V an elastic part VE related to pressure and a plastic part VR enclosed without pressure, so that V= VE+VR [8]. In an experimental study on pig bladders ex vivo VR and VE have been determined at different initial volumes V by a sequence of filling and emptying of a bladder. A remarkable conclusion of that study is that ratio VE/VR is not a constant but varies within the large range of 0.1-0.8. Plastic elongation is recovered by contraction. Distributed spontaneous contraction activity and micromotions have been ascribed a central role in a process of active accommodation of tonic detrusor pressure to volume. Because in present approach the increase of bladder volume is not limited to elastic elongations but to the sum of a variable elastic part, related to pressure VE and a variable plastic part, not related to pressure VR, a specific elastic compliance CE has been introduced defined by CE= ΔVE/Δpdt. Because traditional compliance C is related to the steepness of a cystometrogram we will refer to C as the cystometrographic compliance. C is always larger than CE. While within the considered main range of a cystometrogram cystometrographic compliance C is a constant this does not necessarily imply that also elastic compliance CE is a constant. In present analysis the consequences of the combination of elasticity and plasticity particularly in the range of constant steepness of cystometrograms are considered.

Mechanical Properties of Bladder Tissue

Before deriving volume-pressure relation of total bladder some mechanical properties of bladder tissue of strips excised out of bladder wall are recapitulated, in particular the relation between tension T across a strip and the elongation Δl. The properties are expressed in terms of a discrete mechanical model shown in Figure 2. In this model the distributed elasticity of bladder tissue is lumped and represented by an elastic element or spring SEE. Distributed plasticity of bladder tissue is also lumped and represented by a dashpot or plastic element PCE, set in series with SEE. Because phenomenologically the plastic elongated state of bladder tissue can be reduced by distributed contractile activity of the muscular component, the dashpot represents the combination of plastic elongation (P) and muscular contraction (C) and therefore the dashpot is denoted as a plasto/contractile element PCE. The model of Figure 2 originally has been introduced to describe both the passive and the active properties of bladder tissue in one model.

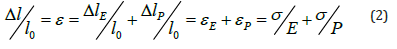

In the model of Figure 2 tension T across the series arrangement is the same across elements SEE and PCE. Total length l is the sum of minimum length l0 and total elongation Δl. The minimum length of the strip l0 is the sum of the minimum length l0E of SEE and the minimum length l0P of PCE, so that l0 = l0E+ l0P. The minimum length of the strip l0 illustrated in Figure 2 is obtained after complete contraction and is related to the amount of tissue of the strip. The separated clustered minimum lengths l0E and l0P both distributed within a strip cannot be measured. The minimum length l0 is a constant sum of minimum length of SEE and of PCE and this total minimum length can be measured. A change in total length Δl is the sum of change of elastic elongation ΔlE and of plastic elongation ΔlP so that,

Figure 2: Mechanical model of passive properties of bladder tissue [8], in shortest contracted state with total length lO and in elongated state with total length l=lO+ΔlO.

Elastic elongation relative to the minimum length of a pure elastic strip (SEE), ΔlE/l0E=εE, is the elastic strain caused by stress σ in the strip in that direction. According to the well-known law of Hooke the ratio of stress σ and small relative elastic elongation εE, is the elasticity parameter E, so that E=σ/εE. If elastic strain is not small and elasticity parameter E depends on the attained elongated state within the range of elongation, then the total elongation ΔlE can be calculated by summation or integration of small elongation steps dlE from actual length lE so that dεE = dlE /l0 =dσ/E(l).

In a similar way the relation between maximum stress σ and the attained plastic elongated state relative to the minimum length of a pure plastic strip (PCE) is expressed by ΔlP/l0P=εP. We define the ratio of maximum stress and attained relative plastic elongation plasticity parameter P, so that P=σ/εP. If plastic strain is not small and plasticity parameter P depends on the elongated state within that range, then total elongation ΔlP can be calculated by summation or integration of small elongation steps dlP from actual length lP so that dεP = dlP /l0 =dσ/P(l).

As in earlier published stress-strain studies we use the initial length of the strip as reference to determine strain. However, the initial length of a bladder strip is not a constant but depends on its previous load. Because the minimum length l0 of a strip is a measurable constant we prefer to use l0 as reference length to calculate εE and εP. Hence with l0 as reference we use instead of (1):

Both E and P are taken as characteristic mechanical parameters of bladder tissue. Next, we introduce a deformation parameter D defined by D=σ/Δl /l0=σ/ε. For infinite small steps in elongation from actual length l we write dε=dσ/D(l). Substitution of this defined D in (2) yields σ/E + σ/P= σ/D, so that,

Deformation parameter D, here used to express the pseudo-static stress-strain relation of bladder tissue, is always smaller than elasticity parameter E and plasticity parameter P. Because the plastic elongated state is determined by the highest previously attained stress, deformation parameter D is useful to calculate the increasing sum of elastic and plastic elongated state of a circumferential strip as part of bladder wall caused by steadily increasing stress during gradually increasing volume in slow filling cystometry.

Values of the parameters E, P can be derived from stress-strain studies in one direction on tissue strips excised out of bladder wall. Experimental values of E of bladder tissue have been published and appear to vary considerably. Experimental values of P are scarce in literature. Parameters E and P include the properties of the muscular component of bladder tissue. To maintain integrity of the muscular component during experiments the strips need to be submerged in a metabolic solution.

Straining in one direction of an excised strip is accompanied by reduction of its width in the transversal direction. For a strip with the same initial geometry but confined as part of intact bladder wall, the transversal effects of straining in one direction are limited by stress generated by the tissue surrounding that strip. The consequence of thus limited transversal effects is that a certain stress in one direction in a confined strip as part of bladder wall causes a smaller elongation in that direction than if the same strip would be excised. Therefore, to use parameters E, P and D derived from stress-strain measurements on excised tissue strips to calculate elongations of a circumferential strip as part of bladder wall, a correction factor needs to be applied. The approximated value of this so-called Poisson correction factor is 2. So, to describe directional stress-strain relations in bladder wall, the values 2E and 2P are used with E and P the values to be derived from excised strips. In (4) D is replaced also by 2D, so that for the stress-strain relation in longitudinal direction of an arbitrarily chosen circumferential strip as part of intact bladder wall with length l we write,

Next, we need to derive the relation between stress σ in bladder wall and tonic detrusor pressure pdt within the bladder, caused by elastic volume VE. We approximate the geometry of a filled bladder by a sphere with radius R, so that.

Application of the law of Laplace, based on equilibrium between pressure pdt within the sphere and force T defined as force per unit circumference of the sphere, yields: T= pdt R/2. For the analysis we need a measure of stress σ in bladder wall. Stress σ is the force per unit area of the thick-walled bladder. For minimum rest volume VR=Vr=0 outside volume of the bladder equals bladder tissue Vt=4/3 πr3, with radius r of a spherical bladder that equals the thickness d of the wall: r=d. Minimum rest volume Vr may be clinically approached by the residual volume Vr after complete micturition. For the minimum circumferential length l0 taken as measure of reference length we can take l0=2πr=2πd. Because for a particular bladder the volume of bladder tissue Vt is constant, an increase of bladder volume V is accompanied by a decrease of thickness d of bladder wall. If radius R of volume V is much larger than radius r of minimum rest volume Vr=Vt, then for thickness d of bladder wall holds: Vt≈4πR2.d. When we divide tension T per unit circumference by thickness d, we get a measure of mean stress σ in bladder wall: σ= pdt R/2d. By substitution of Vt≈4πR2.d we finally get the interesting equation:

Note that equation (7) is based only on geometrical arguments and valid irrespective of what generates stress σ or pressure pdt. In our case stress σ is generated by elastic elongation to enclose VE, while in (7) V is total volume of the bladder. Equation (7) indicates that a constant pressure is obtained if stress σ increases proportional with V. In other words if σ increases proportional with the third power of radius R or with the third power of circumference l=2πR of a spherical bladder or σ:: Δl3, then pdt does not increase with increasing V, if the contribution of radius r of Vt can be neglected as part of radius R of V. This means that deformation modulus D in (5) needs to increase more than linear with the increase of relative elongation ε of circumference of the bladder to obtain a horizontal part of a cystometrogram. To obtain a certain steepness or limited cystometrographic compliance C the increase of deformation parameter D needs to increase even more progressively with ε. By using the definition of CE we write for (7):

The elastic volume VE can be determined by release of the elastic elongation of bladder wall till rest volume VR. In an experimental study the values of VE and VR and CE have been determined on pig bladders with tonic detrusor pressure accommodated to four different volumes by applying sequences of filling, partly emptying and refilling of the bladder. If pdt>0 elastic elongation of circumference ΔlE determining VE is added to rest length lR which determines VR. By substitution of elastic volume VE and accommodated pressure pdt to different values of total volume V we can derive an estimation of the dependency of the elasticity on the length of circumference l of bladder wall. The elastic elongation ΔlE of circumference of a spherical bladder at volume V can be calculated by means of

with VR=V-VE. For the ratio of elastic elongation of circumference ΔlE and stress σ we find by combining (8) and (9):

By substitution of these values in (10) ratio ΔlE/σ has been calculated for the four values of volume of each pig bladder. In Figure 3 the calculated values of ΔlE/σ are shown obtained in seven series of slowly re-filling and re-emptying on pig bladders, each at four sequential larger volumes.

Figure 3: Change of ΔlE/σ as a measure of elasticity related to bladder volume V, calculated by substitution of experimental values of CE and VE [10] in equation (10). Here K1 is a constant.

Each graph in Figure 3 consists of four connected points which correspond to results of four separate measurements on a pig bladder. All the graphs show a downwards trend in ΔlE/σ with increasing volume V, which means that with increasing total volume V the elasticity becomes stiffer or an increasing elasticity parameter E.

Figure 4: Change of lR/σ as a measure of plasticity related to bladder volume V, calculated from the same data used for Figure 3. Here K2 is a constant.

Circumferential rest length lR of a spherical bladder can be calculated from rest volume VR. Because lR is set by the maximum applied stress σ and because the sequence of measurements in concerns increasing volume V, attained lR is limited by the threshold of plastic elongation at that length. In Figure 4 the calculated values of lR/σ are shown obtained from the same measurements used for Figure 3. The graphs in Figure 4 show that the threshold for plastic elongation increases with increasing total volume V, which can be expressed by an increasing plasticity parameter P. Circumference l=lo +Δl of the bladder with volume V is the sum of elastic and plastic elongated state. Figures 3 & 4 indicate that an increase of circumference l is accompanied by a simultaneous increase of E and P according to dependencies on circumference l which are almost similar. Elasticity and plasticity are assumed to be homogeneously distributed features of bladder tissue and hence also homogeneously involved in total elongation Δl. Figures 3 & 4 concern the properties elasticity and plasticity of bladder tissue which are lumped in the separated elements of Figure 2. Figures 3 & 4 indicate that parameters E and P of these elements, in (3) combined in parameter D, are interrelated via volume V as common variable.

To apply equation (2) we need to derive elastic strain εE and plastic strain εP te be derived from ΔlE and ΔlP. In previous stress-strain studies (5) lR was taken as reference length of a strip to determine strain εE. Because rest length lR is variable, in present analysis minimum rest length l0 is preferred as reference to derive strain εE. Of course, the values of strain referred to the longer rest lengths lR are smaller than referred to the constant minimum rest length l0. By using the constant minimum rest length also, the statistical variation of the derived values for E and P will be smaller than with lR as reference length. Furthermore, with lR as reference the considered elongations start from a certain rest volume VR, e.g., from V= 50 ml, while if l0 is used as reference length elongations are considered to start from V=0. In present analysis strains εE, εP and ε are based on l0 as reference (2). In the main part of cystometrograms detrusor pressure pdt commonly increases linearly with increasing total volume V, so that 1/C= dpdt/dV is constant. According to (7) a constant steepness is obtained, when σ increases proportional to V2, hence if σ is proportional to Δl6 . Minimum rest length l0 is constant so that this assumption is fulfilled also if σ is proportional to (Δl/l0)6= ε6. Therefore, we assume for constant steepness:

with constant f2 = (l06/3500) f1.

Substitution of (11) in (7) and differentiation yields:

The theoretical result of (12) shows that, under that the condition of stress-strain relation expressed by (7) and (11), ratio Δpdt/ΔV= 1/C is constant, in agreement with practical cystometrograms. Because in (12) Vt is constant, 1/C =dpd/dV is proportional with factor f1. For the cystometrographic compliance C in the range of 20-40 ml/cm H2O we derive from (12) that f1Vt respectively equals 0.037 -0.019 cm H2O/ml.

A consequence of (11) is that in (5), combined with (3)

In equation (13) the values of E and P are connected to each other via ε as a measure of volume as was supposed earlier from the interpretation of Figures 3&4. From the graphs in Figure 3&4 was concluded also that elasticity parameter E and plasticity parameter P increase progressively with increasing volume V in an almost similar way. According to (13) D needs to increase progressively with the fifth power of relative elongation ε= Δl/l0. So far, the theory is in harmony with the experimental results. For the connection between E and P and fulfilling condition (13) we assume that the εE and εP increase in a similar way with stress σ:

where F is a similarity constant.

This means that during slow-filling relative elastic elongation εE and relative plastic elongation εP may be different but increase in a constant ratio F. This implies that E and P satisfy (13) and depend on actual length l so that.

A consequence of (15) is that the increase of VE and VR, as parts of increasing total volume V, are connected by factor F. VE and VR enclose experimentally separated volumes by two types of mechanical properties which are distributed in bladder wall. Experimentally ratio VE/VR, based on the value of VE by releasing volume VE out of V until pressure pdt=0 and on rest volume VR equal to the remaining volume, is not simply equal to (εE /εP)3 =F3. Because

Factor F determines which part of total elongation Δl of circumference is elastic elongation and which part is plastic elongation. In (17) factor F predicts for each value of V rest volume VR and because VE=V-VR also predicts elastic volume VE and, in this way, hence F predicts ratio VE/VR. As only VE generates detrusor pressure, factor F also determines the relation between pressure pdt and total volume V.

By substitution of (15) in (13) we get:

So, from the simplified analysis based on the model of Figure 2, taking account of observed constant cystometrographic compliance and the assumption of similarity of dependency of elasticity parameter E and plasticity parameter P on strain ε, the following relation between these parameters is derived,

Because of the applied approximations in the simplified theory, exponent 5 in ε5 of (19), which expresses the progressivity of the non-linear dependency of elasticity and plasticity on strain, will not correspond to practical progressivity. So far in our theory F= εE/εP is a constant characterizing a slow filling cystometrogram. In the citated experimental study on pig bladders ratio VE/VR appears to vary in the large range 0.1-0.8 and according to (17) this range corresponds to F= εE/εP in the range of 0.03-0.21, though independent on compliance C. In the next paragraph a physiological explanation is given of the coupling of plastic elongation and elastic elongation by factor F and of the observed variation in this coupling. Dependency of elasticity parameter E on elongated state has been determined experimentally on excised pig bladder strips. Strain in these standard stress-strain measurements relative to actual rest lengths lR of the strips, here denoted by ε1E , are in the range of 0.2 to 1.6.[5]

The experimental values of elastic elongation of bladder wall enclosing VE, used for Figures 3&4 vary in the range of 10-50% of a total bladder volume V, are referred to the prevailing rest length within the range of the stress-strain measurement on strips [9,10]. In that study the data of the dependence of elasticity parameter E on strain ε1E has been fitted by an exponential function according to:

Here E0 is the value of E at rest length lR and k is referred to as a stiffness parameter. For pig bladder strips k has a mean value of 1.28 and standard deviation of 19% [11,12]. Application of an exponential function to fit to stress-strain data is usual. But no theoretical arguments are given to fit here the stress-strain data of bladder tissue by this exponential model. We arrived via a simplified analysis for the dependency of elasticity parameter E on strain ε at a powerfunction (18) instead of an exponential function. Because mathematically xk=eklnx , we can rewrite (18) as an exponential function as follows:

Here E0 is the value of E if ε=0 or if rest length equals minimum circumferential length l0. For ε=0 we find E0= f2(F+1)/F. Equation (21) shows that if we express the theoretical dependence of E on a logarithmic measure of strain instead of Hookean strain ε, then the dependence can be expressed by an exponential like in (20).

Filling a bladder implies large elongations of bladder wall, determined by stress σ and by deformation parameter D which increases progressively with strain. The use of l0 as reference instead of lR yields even larger values of strain. Therefore, it is more appropriate to take account of the change of D(l) in the path of elongation up to Δl. We can consider Δl to be built up by infinite small steps dl, caused by steps in stress dσ, while each step dl is determined by the prevailing value of parameter D expressed in (18), so that dε=dσ/D(l). Then we find Δl as the integral of steps in strain dε yielding ε related to D(ε):

A logarithmic measure of strain known as natural strain εn,= ln(1+ε) may simplify the integration of small elongations up to Δl when deformation parameter D(l) changes significantly within Δl.

In this section it has been shown that the simplified analysis of cystometrograms, within the traject of constant steepness or constant cystometrographic compliance, according to the model of Figure 2 with similar power functions for the dependencies of elasticity parameter E and plasticity parameter P on strain ε combined in (18), yields an explanation of that part of a clinical cystometrogram in terms of passive mechanical properties elasticity and plasticity and in harmony with the experimental results shown in the Figures 3 &4. Figure 5 shows linear parts of two hypothetical slow filling cystometrograms of the isotonic component of detrusor pressure pdt for increasing volume V from 50-400 ml for a bladder with cystometrographic compliance C=20 and 40 ml/cm H2O. Along the illustrated filling trajects the ratios of elastic volume and rest volume VE/VR is constant, determined by a constant similarity factor F. In Figure 5 the parts VE and VR, which are independent of cystometrographic compliance C, are illustrated for V= 300ml. In standard clinical interpretation of cystometrograms the different parts VE and VR of increasing V are not distinguished and the ratio of these parts is not evaluated, while according to the presented model the physiological meaning of VE and VR for the reservoir function of the bladder are basically different: VE is source of pressure pdt and VR controls volume V. Reduction of rest volume VR by contraction activity can be compensated by increasing elastic volume VE accompanied by increasing detrusor pressure. Muscular activity can change the ratio VE/VR. Change of ratio VE/VR during slow filling cystometry will be observed as an interruption of the steady path of the cystometrogram by an increase of detrusor pressure. Spontaneous contraction activity and micromotions have been ascribed a physiological function in active accommodation of detrusor pressure to volume.

Figure 5: Illustrations of cystometrograms according to theory for V in the range from 50-400 ml and cystometrographic compliance C of 20 and 40 ml/cm H2O, with different constant ratios VE/VR for constant similarity factor F. VE and VR are illustrated for V=300 ml.

Figure 6: Schematic illustration of an actomyosin unit as it has been modelled in Figure 2. The number of bridges which connect actin filaments to myosin filaments are dependent on elongation via transversal compression.

Physiological Explanation of Coupled Plasticity to Elasticity

Theoretical stress-strain relations of elastic and plastic elongations and the interdependency and similarity of these non-linear relations based on the model of Figure 2, need to correspond to anatomy and physiology of bladder tissue. The muscular component of bladder tissue can be represented by a network of interconnected small smooth muscle cells. According to the well- known sliding filaments model each smooth muscle cell has contractile units, which are connected on both ends fixed to cell membrane by dense bodies, as illustrated in Figure 6. Each contractile unit consists of thin actine filaments and thick myosin filaments, constituting an actomyosin unit. These filaments can slide along with each other. The myosin filaments can become attached to actin filaments by latch-bridges. Not all bridges are attached to actin filaments. A longitudinal tension across an actomyosin unit may cause slippage of the attachments along the actin filament and elongate the unit. The elongation of an actomyosin unit by slippage behaves mechanically like plasticity. The threshold for this pseudo-plastic elongation of an actomyosin unit is determined by the amount of bridges of myosin filaments attached to the actin filaments. Tension across an actomyosin unit causes also elastic elongation of the filaments in series with plastic elongation. This series arrangement of plastic and elastic elongation of an actomyosin unit corresponds to the model in Figure 2. The mechanical properties of the network of smooth muscle cells can be represented by a network composed of interconnected models of Figure 2, representing connected actomyosin units. Each smooth muscle cell can elongate in all directions, while the model of Figure 2 represents tension or stress and caused elongation only in one direction.

Stress-stain relation of the muscular component of bladder wall, represented by means of a two-dimensional network with the model of Figure 2 as interconnected elements, also concerns elongations in one direction only. But we suppose that the properties of bladder walls with homogeneous structure are similar in all directions. The non-linear stress-strain relations of elastic and of plastic elongation and the interdependency of these relations according to the presented analysis need to be ascribed to the plasticity of slippery characteristics of the myosin filaments along the actin filaments, respectively to the elasticity of the filaments. These different properties depend on the number of attachments of the filaments by bridges as a common factor. The number of attached bridges is related to the actual states of actomyosin units in the network which in principle are different and variable. Stress-strain measurements applied on actin filaments have revealed that the elasticity parameter can be described by an exponential function similar to equation (20) and satisfies the non-linear stress-strain relation concluded from theory. However, only the filaments attached to myosin filaments contribute to overall stress of the network. The distribution of the plastic elongation states of the actomyosin units in the network determines overall plasticity but also the overall elasticity. Hence plastic and elastic elongation are coupled by the distribution of attached filaments as a common factor. The combination of plastic and elastic elongation determines the overall elongation of bladder wall to enclose a certain bladder volume V and consequently determines also ratio VE/VR.

Increasing stress σ with increasing volume according to (7) is resisted by an accordingly heightened threshold of plasticity or parameter P that adapts to increasing stress σ with increasing volume V. This adaptation has been ascribed to a change of the number of attachments by bridges. Thinning down of bladder wall has the consequence of transversal compression on the actomyosin units as illustrated in Figure 5 and this compression facilitates attachment of more bridges. Thinning down of bladder wall is supposed to be accompanied by increase of the number of attachments. In this way threshold of plastic elongation P is related to elongated state of circumference of the bladder so that it increases with total bladder volume V. Consequently, also elasticity decreases with bladder volume. So, plasticity parameter P and elasticity parameter E are coupled by the distribution function of plastic states of actomyosin units and both parameters increase with total volume V as a common factor. Recently Hennig et al [13] have pointed out the bio-mechanical meaning of the thickness of bladder wall in cystometry and have proposed an imaging technique to evaluate the thickness of bladder wall so far applied ex-vivo. From our analysis we conclude that thickness of bladder wall has a particular physiological function in the accommodation of the bladder in the reservoir phase.

Coupling of elastic and plastic stress-strain relations has been specified by the introduction of similarity factor F= εE /εP (14), which also determines ratio VE/VR. It has been stated that in a slow filling cystometrogram F and VE/VR are constants, independent of cystometrographic compliance C. Accommodation of detrusor pressure to volume is realized with different values of ratio VE/VR for equal cystometrographic compliance C. Change of factor F reflects changes of the states of the actomyosin units which may be caused by contraction activity. Experiments have shown that the distribution of the elongated states of actomyosin units can be affected also by pre-straining [14]. Relevance of activity of the muscular tissue component to bring and maintain the bladder in an accommodated state means a partial rehabilitation of the old concept of active control by the muscular bladder wall. However, in the concept presented here the control hypothesis is replaced by an adaptation theory regarding pressure to volume via the plastic elongated state of tissue via change of rest volume VR. The so-called passive properties elasticity and plasticity expressed in parameters E and P and manifest in the ratio VE/VR, do not refer to fixed properties of bladder tissue but are variable properties depending on contraction and straining history of the bladder.

Conclusion

In contrast to other studies of the mechanical properties of bladder tissue in present analysis plasticity has been given a significant meaning in the pressure-volume relation of a bladder. The combination of plasticity and elasticity is involved in the accommodated state of detrusor pressure to volume. Under reference to a discrete mechanical model, total volume V is separated into an elastic volume VE and a rest volume VR. Elastic volume is characterized by elastic compliance CE. Compliance C, determined by the steepness of a slow filling cystometrogram is referred to as cystometrographic compliance C. Rest volume VR is increased by plastic elongation and shortened by contractions. Commonly the steepness of the main part of a cystometrogram is (almost) constant. Constant cystometrographic compliance is obtained by a specific non-linearity of stress-strain relation of bladder tissue. This non-linear relation can be derived by a simplified analysis. By including the assumption of similarity between the stress-stain relation of elasticity and of plasticity, with F as similarity factor, a path with constant cystometrographic compliance is explained. This similarity is obtained by total volume V as a common factor in the stress-strain relations. The variable stress-stain relation of both elasticity and of plasticity of bladder tissue can be explained by a network of connected actomyosin units.

Elasticity parameter E and plasticity parameter P combined to a deformation parameter D determines the relation between elongation of circumference of bladder wall and stress in the wall. Factor F determines the ratio of elastic volume VE and rest volume VR in total volume V and depends on the distribution of the elongated states of actomyosin units in the network, but F is independent of cystometrographic compliance C. During slow filling cystometry of a stable bladder ratio VE/VR is constant, but the maintained value is set by the recent history of contraction and straining of bladder wall. Change of VE/VR during cystometry e.g., caused by spontaneous contraction activity, causes discontinuity in the cystometrogram like by spontaneous transient contraction waves or by change of tonic pressure. Active accommodation is ascribed to active reduction of VR accompanied by compensating increase of VE. As consequence of similarity of stress-strain relations of elasticity and of plasticity, manifestations of VR and VE as different parts of V are masked during slow-filling cystometry. This explains that in clinical situations no distinction is made between contributions of elasticity and plasticity in pressure-volume relation, despite the different meaning of these characteristics for bladder function. Last but not least it is not right to consider the mechanical properties as constant characteristics of passive bladder tissue because of effects of contraction and straining on these characteristics.

References

- Mosso A and Pellacini (1882) On the Function of the Bladder. Arch Ital Biol 1: 97.

- Ausems (1957) De cystometry PhD-thesis Leiden.

- Remington JW (1957) Extensibility behavior and hysteresis phenomena in smooth muscle tissues. In: Remington ed Tissue Elasticity. Am Physiol Soc pp. 138-153.

- Alexander RS (1971) Mechanical aspects of the urinary bladder. Am J Physiol 220(5): 1413-1421.

- Mastrigt R van, Coolsaet BLRA, Duyl WA van (1978) Passive properties of the urinary bladder in the collection phase. Med Biol Eng Comput 16(5): 471-482.

- Abrams P, Blaivas JG, Stanton SL, Anderson JT (1988) The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function. The International Continence Society Committee on Standardization of Terminology. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl 114: 5-19.

- Wyndaele JJ, GammieA, Bruschini H, De Wachter S, Fry CH, et al (2011) Bladder compliance what does it represent:can we measure it, and is it clinically relevant? Neurourol Urodyn 30(5): 714-722.

- Duyl W.A. van (1985) A model for both the passive and active properties of urinary bladder tissue related to bladder function. Neurourol Urodyn 4(4): 275-283.

- Duyl WA van, Coolsaet BLRA (2021) Biomechanics of the urinary bladder: spontaneous contraction activity and micromotions related to accommodation. Int Urol Nephrol 53(7): 1345-1353.

- Duyl WA van (2021) Biomechanics of urinary bladder: slow-filling and slow-emptying cystometry and accommodation. Bladder 8(1): e45.

- Frank O (1910) The stretching of a spherical bubble. Journal of Biology 54: 531-532.

- Mastrigt R van (1977) A system approaches the passive properties of the urinary bladder in the collection phase. Erasmus University Rotterdam, Netherlands.

- Duyl W.A. van (2022) Accommodated tonic detrusor pressure determined by the combination of variable elastic volume and variable elastic compliance explained by means of sliding filaments model. J Urol Neph St 4(1): 357-370.

- Hennig G, Saxena P, Broemer E,Herrera GM, Roccabianca S, Tykocki (2022) Quantifying whole bladder biomechanics using the novel pentaplanar reflected image macroscopy system. Research Square p. 1-17.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...