Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1687

Research Article(ISSN: 2641-1687)

Clinical Characteristics of Malformations of The Lower Urinary Tract (Distal Ureter and Urinary Bladder) Surgically Treated in A Ten-Year Period Volume 4 - Issue 2

N. Imamović1, K. Karavdić2*,D. Miličić-Pokrajac3

- 1Medical Faculty,University of Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Europe

- 2Clinic for Pediatric Surgery, Clinic Center of University Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Europe

- 3Nephrology Departement, Pediatric Clinic, Clinic Center of University Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Europe

Received: January 26, 2022; Published: February 03, 2023

Corresponding author: K. Karavdić, Clinic for Pediatric Surgery, Clinic Center of University Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Europe

DOI: 10.32474/JUNS.2023.04.000183

Abstract

Introduction: Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) make up to 20-30% of all congenital anomalies discovered prenatally1. Since these defects are the most common cause of the end-stage renal disease and requirement of RRT (Renal replacement therapy) in children and adolescents, forehand diagnostic and right treatment is utmost required, so we might forestall the complications.

Methods: Data used was collected from the Pediatric Surgery department of the Clinical center of University of Sarajevo’s archive, in the timeframe from 2010 to 2020, from patients’ histories who met the requirements of inclusion criteria and didn’t have any of the exclusion criteria. The goal was to determine the prevalence, presentation, investigate the clinical characteristics and describe the treatment of birth anomalies of the lower urinary tract that were surgically treated in the Clinic, as well as compare the results with those available in the literature.

Results: Urogenital birth defects make up to 7,8% of all surgeries in the given period, with birth defects of the lower urinary tract making up to a bit more than ⅕ of the latter ones. Clinical characteristics of these anomalies indicate that a significant number of them probably needed surgical treatment even before they were referred to a pediatric surgeon (irreversible damage to kidney parenchyma) , though alternative and less invasive options were widely considered.

Conclusion: A significant number of all the surgeries done, especially if we’re considering CAKUT, accounts for the surgeries of the lower parties of the system, which - along with satisfying results of surgical treatment - shows that adequate diagnosis and considering surgical treatment are keys to preventing later complications in adult age, and that it takes approx. between one and two hospitalizations until total resolution, as well as continuous education of medical staff in treating these anomalies.

Keywords: Birth Defects; development anomalies; urinary tract; pediatric urology

Introduction

By the anomalies of the lower urinary tract that this paper deals with: ureter duplex, congenital megaureter, ureteral atresia, juxtavesical stenosis of the ureter, primary vesicoureteral reflux, exstrophy of the urinary bladder, neurogenic bladder (excluding congenital anomalies of the urethra and genital tract, which are embryonically and developmentally linked for those mentioned above, and malformations of the upper urinary tract that are not the result of changes in the lower urinary tract). The reported incidence of all genitourinary anomalies (since they are considered together for their embryonic origin) is 1 in 500-600 live births, while the detection of moderate dilatation is more common - 1 in 100 pregnancies (often a transient condition) [1-5]. This number varies depending on the method of detection - prenatal/ postnatal - and the sensitivity of the tests [6-8]. In prenatal screening, genitourinary anomalies represent as much as 50% of all anomalies detectable by ultrasound, and hydronephrosis accounts for 2/3 of these anomalies [9-12]. In terms of obstructive uropathy, supravesical ones are much more common than infravesical ones, and unilateral ones are more common compared to bilateral ones (although most often there is medium-severe contralateral hydronephrosis due to obstruction). Among the syndromes that often include genitourinary anomalies:

a) Trisomy 13: hydroureter/hydronephrosis, double collecting system and polycystic kidneys.

b) Trisomy 18: horseshoe kidney, double collecting system, unilateral renal agenesis, hydronephrosis, nephroblastoma, pyeloureteric neck stenosis, cystic kidney disease.

c) Turner syndrome: horseshoe kidney, double collecting system, unilateral renal agenesis, hydronephrosis.

d) Chromosomes 4 and 7: primary vesicoureteral reflux

e) Chromosome 17: megaureter

Also, it can be related to certain fewer common syndromes:

a) Beckwith-Wiedemann – hydroureter/hydronephrosis (autosomal dominant).

b) Silver-Russel – primary vesicoureteral reflux, reflux uropathy (autosomal recessive).

c) Congenital generalized lipodystrophy - hydroureter/ hydronephrosis (autosomal recessive) [13-17].

Methods

The medical histories of patients from the Archives of the Children’s Surgery Clinic of the Clinical Center of the University of Sarajevo, surgically treated between 2010 and 2020, were used as a data source. The methods by which the data are presented are methods of descriptive statistics. Due to the availability of the patient’s documentation, the aggregated search results are relativized to the number of available data. Hospitalizations of patients for other indications, if there were any in the given period, were not included. In the case of multiple hospitalizations, data on clinical characteristics were taken from the initial findings of nephrological and urological examinations. Scientific database searches included MeSH terms: pediatric, urology, urinary tract, congenital, birth defects, congenital anomalies, CAKUT. The results of the nephrology tests are unified as follows, for the sake of comparison:

a) Dynamic scintigraphy: presence/absence of obstruction.

b) Static scintigraphy: existence/absence of scarring changes.

c) EHO/MRI: measured width of the ureter in the widest part in the diagnosis of vesicoureteral reflux and juxtavesical stenosis, pathological thickness of the bladder wall.

d) MCUG: in how many cases of EHO verified dilatation of the system was the presence/absence of reflux described.

e) Cystoscopy: physiological/pathological findings.

f) Urodynamics: finding satisfactory/unsatisfactory.

about Lab. findings: the existence of deviations preoperatively and postoperatively

Inclusion criteria

Patients hospitalized at the Clinic in the period from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2020 for surgical treatment of congenital anomalies of the lower urinary tract (ureter and bladder), admitted under the following diagnoses: ureterocoele, ureter duplex, stenosis juxtavesicularis, reflux vesicoureteralis, ureterohydronephrosis, vesica neurogenes, non-neurogena vesica neurogenes, extrophio vesicae.

Exclusion criteria

a) Patients whose surgical treatment was started before the follow-up period.

b) Patients with associated anomalies of the upper urinary tract that are not the result of changes in the lower urinary tract.

Results

The total number of anomalies of the urogenital tract surgically treated in the observed period was 495, and of that, the number of anomalies of the lower urinary tract accounted for a little more than a fifth, 21.21%, which is shown graphically (Figure 1).

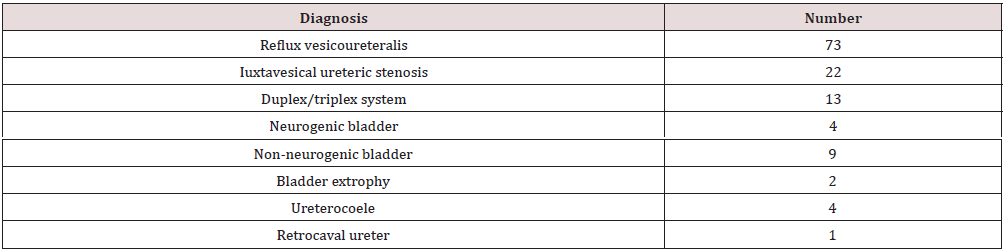

The representation of certain anomalies (according to admission diagnosis) is as follows (Table 1):

Figure 1: Representation of anomalies of the lower urinary tract (green 17,5% lower urinary tract, blu 82,5% urinary tract).

The number of hospitalizations by year is presented graphically (Figure 2).

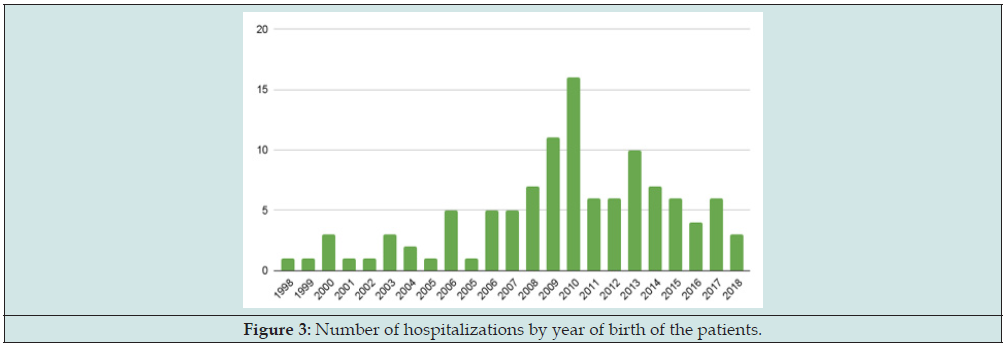

The number of hospitalized patients by their year of birth is presented in the following Figure 3:

The average age of first hospitalization was 3.53 full years of life. The share of female children is higher - 53.55%, compared to the share of male children - 46.45% (Figure 4).

19.9% were detected prenatally, and 80.1% postnatally, of all monitored anomalies in the given period (Figure 5):

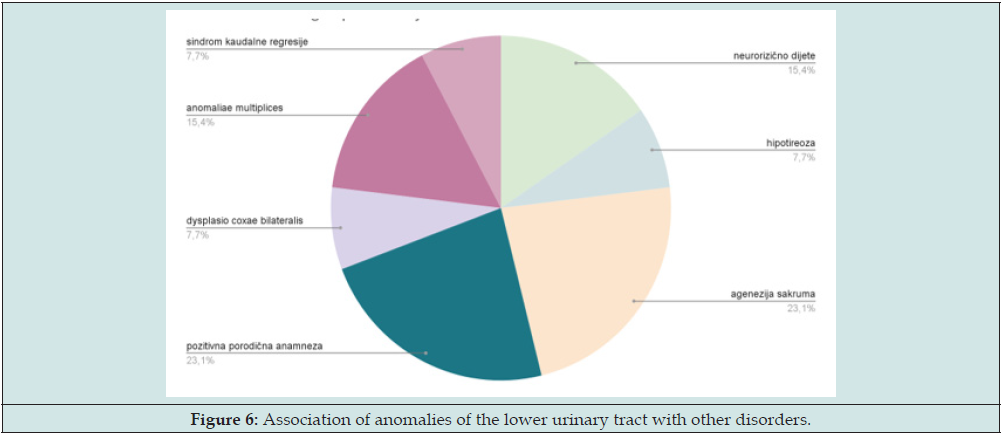

The first symptoms appeared on average at the age of 2.6 full years, and by frequency as in the following graph. A total of 13.35% of patients reported specificities in their anamnesis, in terms of association with other developmental anomalies and pathological conditions (distribution on the graph) (Figure 6):

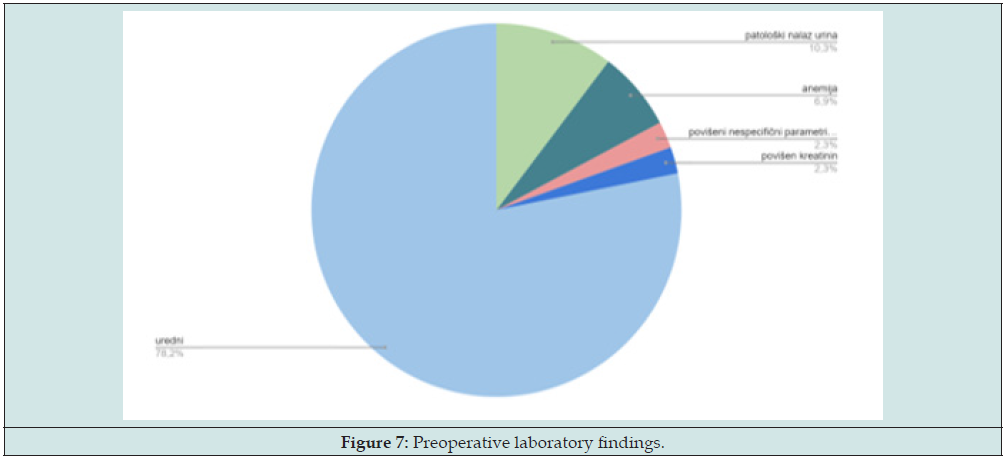

Preoperative laboratory findings, performed as part of the patient’s preoperative preparation, in the available documentation, showed the following (Figure 7):

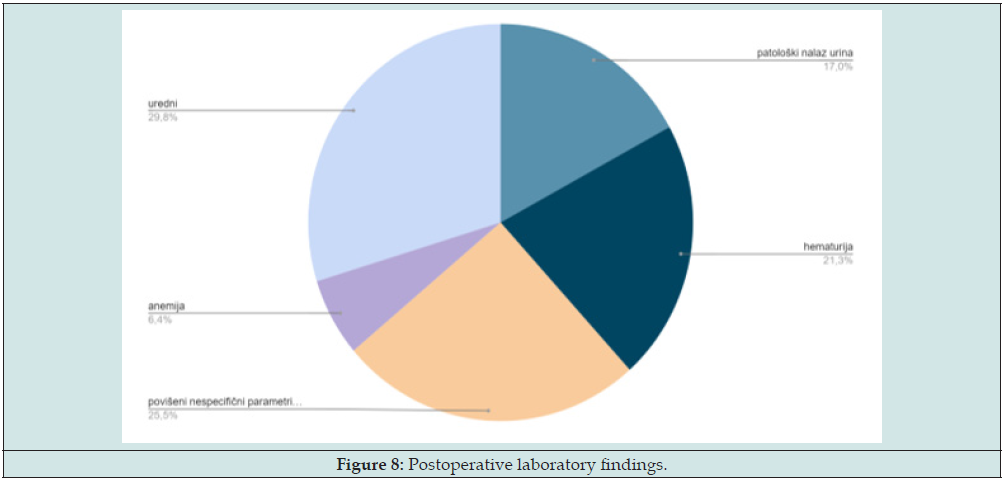

Postoperative laboratory findings, in the available documentation, included initial findings made after the procedure, and the representation of individual findings is as follows (Figure 8):

The initial finding of echo sonography of the urinary tract was normal in only 5 cases, which is 4.8% of the total number. Dilatation of the system (described by the terms ureter hydronephrosis, megaureter) was present in 54 cases, of which 79.63% was responsible for reflux, and 20.37% was the result of distal (juxta vesical) stenosis of the ureter, which was confirmed by the finding of voiding cystoureterography. The findings of cystoscopy in 94.92% of cases showed pathological changes, which refers to any deviation from the physiological characteristics of the bladder mucosa or normoposition and the normal appearance of the ureteral orifices in the area of the trigone of the bladder. In 45.76% of hospitalized patients, there were changes in the urinary bladder, in the form of a changed appearance of the mucosa, thickening of the wall, or the presence of trabeculae or diverticula (Figure 9). Urodynamics findings were satisfactory in 45.45% of cases (referring to an adequate bladder filling and emptying phase, with the presence of coordinated contractions of the bladder detrusor and urethral sphincter to ensure adequate filling and emptying, without pathological pressure increase in the bladder depending on fullness, and no residual urine), and in 40.90% it was unsatisfactory, and in 13.63% of cases, due to the child’s age, it was not possible to perform the search even though it was indicated, which is shown graphically (Figure 10):

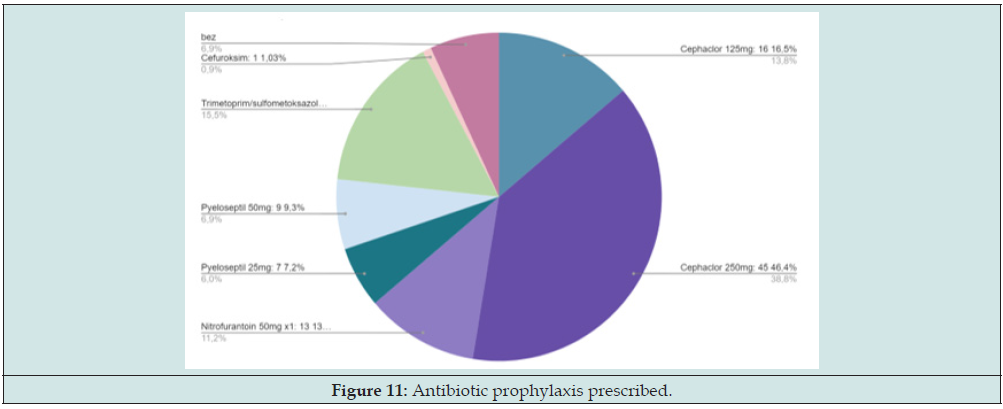

Scarring changes on static scintigraphy were present in slightly more than half of the patients - 52.78%. Obstruction on dynamic scintigraphy (absence of elimination of radiopharmaceuticals from the renal collecting system even after the application of diuretics in the 15’ of the study) was present in 7.7%, and the initial reduced relative function on the damaged side (in case of unilateral anomalies) was proven in 34.52 % of cases. The postoperative EHO of the urotract was adequate (expected postoperative finding, without subsequent obstruction/dilatation) in all patients. A total of 97 patients were on antibiotic prophylaxis, of which: Cephaclor 125mg 16.5%, Cephaclor 250mg: 46.4%, Nitrofurantoin 50mg 13.4%, Pyeloseptil 25mg 7 7.2%, Pyeloseptil 50mg: 9 9.3%, Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole syrup 18.56%, Cefuroxime 1 .03%, graphically shown (Figure 11):

The average number of hospitalizations in the follow-up period for one patient is 1.6 and the average number of days spent in hospital per patient is 15.7, with the highest total days spent in the case of diagnosis Vesica neurogenes, Hydronephrosis l sin cum reflux vesicoureteralis l sin gr V, Hypofunctio renis l sin - as many as 104, and the least in the case of a diagnosis of Reflux vesicoureteralis l. dex. et ureterocele l. dex. - only 1. The proportion of patients who required a certain type of surgical intervention amounts shown in Figure 12:

Figure 12: Type of surgical intervention performed (yellow 21,9%open, blu endoscopic 54,3%, pink 23,8% both).

Type of surgical intervention performed (yellow 21,9%open, blu endoscopic 54,3%, pink 23,8% both).

Discussion

The total number of anomalies of the urogenital tract surgically treated in the observed period was 495 (which is 7.8% of all operations in the given period), and of that, the number of anomalies of the lower urinary tract makes up a little more than a fifth, 21.21%. The share of female children is slightly higher - 53.55% - compared to the share of male children - 46.45%.In the available literature, there are no data related only to the demographic and epidemiological data of malformations of the distal ureter and urinary bladder, but studies dealing with anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract indicate that these are one of the most common malformations, with a prevalence of 1 in 500 live births and with equal distribution by gender, and which occupy as much as 20-30% of prenatally detected anomalies [18-21]. About 34-59% of those born with these malformations developed chronic kidney disease, the most common of which was obstructive uropathy [22-25]. In our patients, 19.9% were detected prenatally, and 80.1% postnatally, of all monitored anomalies in the given period. For example, most primary obstructed ureters are picked up by prenatal screening, and most of them are asymptomatic.

Brown et al. (1987) clearly demonstrated that the majority of primary obstructed ureters (79%) were detected antenatally - accounting for 23% of prenatally diagnosed dilatations, compared to the time before the existence of ultrasound screening, where only 8% of patients presented symptomatically and with consequent dilatation of the upper urinary tract [26,27]. Since postnatally these malformations were most often presented as febrile infections of the urinary tract in our patients, it is important to note that this is a very important factor in (primarily small) children, in whom the symptomatology in quite a few cases is non-specific, and they are often unable to be reliably diagnosed. recognize and present. In this year’s study, it was estimated that the median symptom onset was 2 years, compared to the 3 years of life described in earlier studies, which in our patients is 2.6 full years of life [28-30]. According to the literature, obstructive disorders presented themselves earlier [31-34]. A total of 13.35% of patients reported specificities in their anamnesis, in terms of association with other developmental anomalies and pathological conditions or a positive family history of these anomalies. In almost a quarter of the cases, it was agenesis of the sacrum, and the same number of patients had a positive family history.

A study from 2019 showed that the most common comparative anomalies are congenital malformations of the heart - 8.89% (if we talk about all anomalies of the kidneys and urinary tract) [35].

No isolated data for the anomalies discussed in this work were found. Family systematic review studies showed the existence of a predisposition and implied a genetic origin of vesicoureteral reflux. About 45-50% of children with primary vesicoureteral reflux come from families in which at least one other member has been treated for it. The disease often occurs in two or more generations, with a 65% chance of being passed from parent to child, and 34-45% of siblings of patients also have reflux. Also, one study showed that 80% of identical twins and 35% of fraternal twins developed primary vesicoureteral reflux. All these data strongly support the genetic basis of vesicoureteral reflux and are in agreement with an autosomal dominant type of inheritance with incomplete penetrance [36]. The existence of these anomalies, primarily neurogenic bladder, may be indicative of the existence of spina bifida (occludae) if it has not been previously diagnosed [37]. Preoperative findings were completely normal in ⅘ cases, which is expected given that the majority of patients were already fully nephrologically processed and often treated conservatively before coming to the pediatric surgeon.

In some centers, it was estimated that routine laboratory diagnostics are not indicated in healthy children, and that all tests should be based on the general health of the patient (is the child younger than 6 months, was he born prematurely,) and in connection with the procedure which is performed (whether intraoperative bleeding is expected, etc). Routine coagulation tests and a history of easy bruising are not adequate to predict intraoperative bleeding [38]. As for specific markers for renal damage, children with susceptible structural changes in the renal parenchyma may not have an increase in serum creatinine, due to the existence of renal reserve - ie. capacity of nephrons to maintain glomerular filtration through compensatory hypertrophy and hyperfiltration. Also, its values can be affected by race, sex, muscle mass, hydration status, and medications, so changes in serum creatinine values may not represent equivalent changes in renal function in all patients [39]. The findings of cystoscopy showed pathological changes in 94.92% of cases, which refers to any deviation from the physiological characteristics of the bladder mucosa (without altered appearance of the mucosa, thickening of the wall, or the presence of trabeculae or diverticula) or normoposition and normal appearance of the ureteral orifices.

A normal ureteral orifice means that it is positioned in the trigone of the bladder (not ectopic), that it is passable for the probe and that it is not visualized as open (gaping, horseshoe, golf hole-sized, or stadium-shaped). In slightly less than half of the hospitalized patients, there were changes in the mucous membrane of the urinary bladder. A normal urodynamics finding, in the case of our patients in almost half of the cases, implies a normal capacity and synchronous activity of the bladder detrusor and urethral sphincter, maintained bladder compliance that allows the bladder to be emptied adequately (without residual urine, obstruction at the exit and reflux - which reduces the incidence of urinary tract infections) and adequately serves as a reservoir of urine (without disturbances in the relationship between pressure and capacity). Bladder capacity is calculated according to Koff’s (age-related bladder capacity) formula: [(years x 30)/2]. There was a total of 97 patients on antibiotic prophylaxis, of which: Cephaclor 125mg 16.5%, Cephaclor 250mg: 46.4%, Nitrofurantoin 50mg 13.4%, Pyeloseptil 25mg 7 7.2%, Pyeloseptil 50mg: 9 9.3 %, Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole syrup 18.56%, Cefuroxime 1.03%. The use of antibiotic prophylaxis is widely represented, and there is a continuous debate about its usefulness and the moment when surgical treatment is necessary, with the aim of early resolution and prevention of complications.

Of course, such a regimen is not always and completely possible to implement ideally, and what can be influenced by it - the regimen and type of antibiotic prophylaxis, whether it is in all cases better than treating an acute infection when it occurs, what is the optimal duration of it, whether In some cases, endoscopic treatment can be considered the first line of treatment in children with low-grade and medium-severe VUR, and what is the general benefit of conservative treatment. Scarring changes on static scintigraphy were present in slightly more than half of the patients, and obstruction on dynamic scintigraphy (absence of elimination of radiopharmaceuticals from the collecting system of the kidneys even after the application of diuretics in the 15’ study) was present in only 7.7%, and the initial reduced relative function on the damaged side (in case of unilateral anomalies) was demonstrated in a third of cases. In any case, studies have shown that there is a lower incidence of renal scarring in patients in whom VUR is detected by screening before it is detected by (often recurrent or persistent) urinary tract infections.

In their retrospective analysis of 303 children up to 2 years of age, with urinary tract infections confirmed by urine cultures, Swerkerson et al. revealed the presence of vesicoureteral reflux in 22% of subjects, with scarring of the renal parenchyma in 26% of them (with the help of DMSA scintigraphy). The relative risk for scarring was significantly higher for grade II reflux and higher [40]. More recent studies made a distinction and found that children with primary reflux have scars in over 50% of cases, and that DMSA scintigraphy is much more sensitive than ultrasound for the discovery of these consequences [41]. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are not suitable for screening, but they provide precise anatomical details and increase the diagnostic specificity of other examinations [42]. When it comes to open surgical methods, in general, good results are evident in megaureter reduction techniques, with success rates as high as 90% to 95%. But when it comes to the available treatments for primarily obstructed ureters, be they endoscopic or open, they are still invasive - primarily for small bladders and ureters of children under one year of age, where the incidence of complications is much higher and the performance of the procedure itself is very difficult.

For this reason, there was a need to consider additional, less invasive methods and those with fewer complications, in which balloon-dilation of the ureter proved to be an excellent transurethral intervention (KCUS has not yet been implemented at the Children’s Surgery Clinic). According to the available literature, the best outcomes were recorded in the group of patients with primarily obstructed ureters (with an emphasis on open methods), and the worst in the group of those with dysfunctional voiding and neurogenic bladder. Long-term follow-up was missing in several studies dealing with similar disorders. Data from the European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association Registry imply that RRT (renal replacement therapy) - dialysis - for end-stage renal disease is needed earlier in patients with congenital anomalies of the kidneys and urinary tract (31 years of age) compared to others (61 years age), which conditions the need to create databases for a long time.

Conclusion

Anomalies of the lower urinary tract thus constitute a significant part of all urogenital anomalies and are a common cause of terminal renal failure. The diagnosis can be made prenatally, during routine ultrasound examinations of a pregnant woman, and the presence of oligohydroamnion and slow progress in development (small for gestational age) can raise doubts about the existence of these types of malformations. The diagnosis is most often made postnatally due to recurrent infections of the urinary tract, often accompanied by fever, at the age of up to 3 years. A nonspecific presentation is characteristic of the pediatric population. Timely diagnosis and treatment of anomalies of the lower urinary tract prevents the appearance of scintigraphically verified scars on the renal parenchyma.

Adequate preparation of the patient by the competent pediatrician and family physician, continuous nephrological monitoring, laboratory (biochemical and microbiological) findings, radiological and scintigraphic analyses, and response to antibiotic prophylaxis are factors that contribute to the decision whether the child should be referred to a pediatric surgeon and evaluated in terms of surgical treatment. Surgical treatment is necessary in most patients with anomalies of the lower urinary tract. Timely diagnosis and adequate treatment are key to preventing complications that inevitably affect the quality of life of patients and the burden on both parents and the health system, as well as affecting the child’s development. In order to ensure adequate health care (timely diagnosis and treatment), continuous education of medical personnel who are actively involved in the treatment of lower urinary tract anomalies (pediatric nephrologists, pediatric surgeons, radiologists, anesthesiologists, nuclear medicine specialists, medical technicians/nurses) is necessary.

References

- Queisser-Luft A, Stolz G, Wiesel A, Schlaefer K, Spranger J (2002) Malformations in newborn: results based on 30,940 infants and fetuses from the Mainz congenital birth defect monitoring system (1990-1998). Arch Gynecol Obstet 266(3): 163-167.

- Aida Hasanović (2016) Anatomy of Internal Organs. University of Sarajevo.

- TW Sadler (2012) Langman’s medical embryology. Wolters Kulwer, USA.

- David FM Thomas, Patrick G Duffy, Anthony MK Rickwood (2015) Essentials of Pediatric urology, second edition, Informa healthcare.

- Siomou E, Papadopoulou F, Kollios KD, Photopoulos A, Evagelidou E, et al. (2006) Duplex collecting system diagnosed during the first 6 years of life after a first urinary tract infection: a study of 63 children. J Urol 175(2): 678-681.

- Milicevic S, Bijelic R, Krivokuca V, Jakovljevic B (2018) Duplex System with Ectopic Ureter Opens into the Posterior Urethra: Case Report. Med Arch 72(2): 145-147.

- Alan J. Wein, Louis R. Kavoussi, Alan W. Partin, Craig A. Peters, Scott McDougal (2016) Campbell-Walsh Urology, 11th edition, Elsevier.

- Share JC, Lebowitz RL (1989) Ectopic ureterocele without ureteral and calyceal dilatation (ureterocele disproportion): findings on urography and sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 152(3): 567-571.

- Bleve C, Conighi M, Fasoli L, Bucci V, Valeria B, et al. (2017) Proximal ureteral atresia, a rare congenital anomaly-incidental finding: A case report. Transl Pediatr 6(1): 67-71.

- Laurence S. Baskin, Barry A. Kogan, Jeffrey A. Stock (2019) Handbook of Pediatric Urology, 3rd edition, Wolters Kluwer.

- Hoebeke P, Walle J, Everaert K, Laecke E, Van J (1999) Assessment of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction in Children with Non-Neuropathic Bladder Sphincter Dysfunction. Eur Urol 35(1): 57-69.

- Austin PF, Bauer SB, Bower W, Chase J, Franco I, et al. (2016) The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: Update report from the standardization committee of the International Children's Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 35(4): 471-481.

- Hoebeke, Renson C, Petillion L, Walle J, Paepe H (2002) Percutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation in Children with Therapy Resistant Nonneuropathic Bladder Sphincter Dysfunction: A Pilot Study. J Urol 168(6): 2605-2607.

- Burgers RE, Mugie SM, Chase J, Cooper CS, Gontard AV, et al. (2013) Management of functional constipation in children with lower urinary tract symptoms: report from the Standardization Committee of the International Children's Continence Society. J Urol 190(1): 29-36.

- Farhat W, Bägli DJ, Capolicchio G, O’Reilly S, Merguerian Pa, et al. (2000) The dysfunctional voidning scoring system: quantitative standardization of dysfunctional voiding symptoms in children. J Urol 164(3 pt 2): 1011-1015.

- Barry O'Donell, Stephen A. Koff (1997) Pediatric Urology, 3rd edition.

- Shokeir AA, Nijman RJ (2000) Primary megaureter: current trends in diagnosis and treatment. BJU Int 86(7): 861-868.

- Smellie JM, Tamminen-Möbius T, Olbing H, Claesson I, Wikstad I, et al. (1992) Five-year study of medical or surgical treatment in children with severe reflux: radiological renal findings. The International Reflux Study in Children. Pediatr Nephrol 6(3): 223-230.

- Mandell J, Bauer SB, Hallett M, Khoshbin S, Dyro FM, et al (1980) Occult spinal dysraphism: a rare but detectable cause of voiding dysfunction. Urol Clin North Am 7(2): 349-356.

- Hoebeke P, Vande Walle J, Everaert K, Van Laecke E, Van Gool JD (1999) Assessment of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction in Children with Non-Neuropathic Bladder Sphincter Dysfunction. Eur Urol 35(1): 57-69.

- Urodynamic Testing. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

- Prasad Godbole, Duncan T. Wilcox, Martin A. Koyle (2021) Practical Pediatric Urology, An Evidence-Based Approach. Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

- Ranawaka R, Hennayake S (2013) Resolution of primary non-refluxing megaureter: An observational study. J Pediatr Surg 48(2): 380-383.

- Aseem R. Shukla, Jeffrey Cooper, Rakesh P Patel, Michael C Carr, Douglas A Canning, et al. (2005) Prenatally detected primary megaureter: A role for extended followup. J Urol 173(4): 1353-1356.

- Marie-Klaire Farrugia, Rowena Hitchcock, Anna Radford, Tariq Burki, Andrew Robb, et al. (2014) British Association of Paediatric Urologists consensus statement on the management of the primary obstructive megaureter. J Pediatr Urol 10(1): 26-33.

- Peter C Fretz, J Christopher Austin, Christopher S Cooper, Charles E Hawtrey (2004) Long-term outcome analysis of Starr plication for primary obstructive megaureters. J Urol 172(2): 703-705.

- Wojciech Perdzynski, Zygmunt H Kaliciński (1996) Long-term results after megaureter folding in children. J Pediatr Surg 31(9): 1211-1217.

- KE Whitmore, RM Ehrlich (1988) Vascular Integrity of the Distal Ureter following Combined Tapering and Cross Trigonal Reimplantation. J Urol 139(3): 621-624.

- David M Kitchens, William DeFoor, Eugene Minevich, Pramod Reddy, Ethan Polsky, etal. (2007) End Cutaneous Ureterostomy for the Management of Severe Hydronephrosis. J Urol 177(4): 1501-1504.

- Wolfgang H Cerwinka, Hal C Scherz, Andrew J Kirsch (2008) Endoscopic Treatment of Vesicoureteral Reflux with Dextranomer/Hyaluronic Acid in Children. Adv Urol 2008: 513854.

- Giovanni Torino, Agnese Roberti, Elisa Brandigi, Francesco Turrà, Antonio Fonzone, et al. (2021) High-pressure balloon dilatation for the treatment of primary obstructive megaureter: is it the first line of treatment in children and infants? Swiss medical weekly 151(2324): 1-7.

- Javairia Shakoor, Naureen Akhtar, Shahida Perveen, Ghulam Mujtaba Zafar, Adeela Chaudhry, et al. (2020) Clinical And Morphological Spectrum Of Congenital Anomalies Of Kidney And Urinary Tract (Cakut) - A Tertiary Care Center Experience. Pak Armed Forces Med J 70(5): 1565-1570.

- Lu J, Liu X, Wei Y, Yu C, Zhao J, et al. (2022) Clinical and Microbial Etiology Characteristics in Pediatric Urinary Tract Infection. Front Pediatr 10: 844797.

- Soliman NA, Ali RI, Ghobrial EE, Habib EI, Ziada AM (2015) Pattern of clinical presentation of congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract among infants and children. Nephrology 20(6): 413-418.

- Li ZY, Chen YM, Qiu LQ, Chen DQ, Hu CG, et al. (2019) Prevalence, types, and malformations in congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract in newborns: a retrospective hospital-based study. Ital J Pediatr 45(1): 50.

- Rasouly HM, Lu W (2013) Lower urinary tract development and disease. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 5(3): 307-342.

- Stephen J Falchek (2018) Overview of Congenital Neurologic Anomalies. MSD Manual.

- Steward DJ (1991) Screening tests before surgery in children. Can J Anaesth 38(6): 693-695.

- Greenberg JH, Kakajiwala A, Parikh CR, Furth S (2018) Emerging biomarkers of chronic kidney disease in children. Pediatr Nephrol 33(6): 925-933.

- Svante Swerkersson, Ulf Jodal, Rune Sixt, Eira Stokland, Sverker Hansson (2007) Relationship Among Vesicoureteral Reflux, Urinary Tract Infection and Renal Damage in Children. J Urol 178(2): 647-651.

- Bundovska-Kocev S, Kuzmanovska D, Selim G, Georgievska-Ismail L (2019) Predictors of Renal Dysfunction in Adults with Childhood Vesicoureteral Reflux after Long-Term Follow-Up. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 7(1): 107-113.

- Teresa Berrocal, Pedro López-Pereira, Antonia Arjonilla, and Julia Gutiérrez (2002) Anomalies of the Distal Ureter, Bladder, and Urethra in Children: Embryologic, Radiologic, and Pathologic Features. Radiographics 22(5): 1139-1164.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...