Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1687

Research Article(ISSN: 2641-1687)

Acute Cystitis: A Review and Update Volume 4 - Issue 1

Anthony Kodzo-Grey Venyo*

- **North Manchester General Hospital, Department of Urology, Manchester, United Kingdom

Received: December 21, 2022; Published: January 06, 2023

Corresponding author: Anthony Kodzo-Grey Venyo, North Manchester General Hospital, Department of Urology, Manchester, United Kingdom

DOI: 10.32474/JUNS.2023.04.000178

Abstract

Acute cystitis is a terminology that is utilized for a clinical diagnosis, which most often comprises of a triad of manifestations including: urinary frequency, lower abdominal pain and dysuria (pain or burning during micturition). It has been noted that in acute cystitis, there usually tends to be no surgical specimen before a clinical diagnosis of acute cystitis is provisionally made by clinicians; even though acute cystitis could be a finding which had been made based upon specimens which had been obtained for other reasons or based upon findings during autopsy examinations. It has been known that acute cystitis has tended to be common among young women, who are within their reproductive ages, as well as in older women and older men. Acute cystitis does tend to affect the urinary bladder or the urethra (lower urinary tract). Acute cystitis tends to be caused by a number of agents / scenarios. It has been iterated that the most common bacterial agents that have tended to cause acute cystitis include Escherichia coli, Proteus, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter. It has also been known that acute cystitis has also tended to be caused by Candida, or Cryptococcus in immune-compromised individuals, Schistosoma haematobium within Egypt and in areas along River Nile, as well as by adenovirus, chlamydia, and mycoplasma.

Non-infectious causes of acute cystitis have also been diagnosed and managed including chemotherapy causes, radiotherapy as well as trauma. It has been known that with regard to cases of Escherichia coli acute cystitis, the faecal flora of the host and with regard to women, vaginal flora, had tended to be commonest immediate source for the infecting strain. It has additionally been iterated that the Escherichia coli strain could represent the most prevalent faecal/vaginal Escherichia coli clones of the individual and this iteration has been based upon the prevalence hypothesis, or the Escherichia coli strain could represent a distinctive, highly selected sub-set of the faecal / vaginal Escherichia coli population which has tended to be associated with enhanced virulence potential that has been iterated based upon the special-pathogenicity postulate (hypothesis). Some of the clinical features of acute cystitis that had been documented include the ensuing: Some patients could be asymptomatic; some cases of acute cystitis could be caused by lower urinary tract obstruction, cystocele, or diverticula of the urinary bladder; Some cases of acute cystitis could emanate in the development of pyelonephritis; uncomplicated cases of acute cystitis do tend to occur in otherwise healthy nonpregnant adult ladies.

Complicated cases of acute cystitis tend to be associated with conditions which do increase the risk of treatment failure, such as an episode of an upper urinary tract infection, or a drug-resistant pathogen, and for complicated cases of cystitis, utilization of a broader spectrum antimicrobial agents had been recommended for successful treatment of such cases. With regard to uncomplicated acute cystitis, this has tended to be associated with excellent prognosis and in such cases the symptoms had tended to resolve within 1 day to 2 days after treatment. Diagnosis of acute cystitis has tended to be established based upon obtaining of good clinical history, and clinical examination which would enable the clinician to establish a provisional diagnosis and the diagnosis could usually be confirmed based upon urinalysis, urine microscopy, and culture and sensitivity most often. With regard to initiation of treatment for acute cystitis, the suggested clinical algorithm indicators include clinicians should treat the patients empirically with antibiotics if 2 of the 3 ensuing variables are present: (a) dysuria, (b) urine WBC > trace, (c) urine nitrites); otherwise, clinicians should obtain culture and wait for results of the microbiology tests. Complicated cases of acute cystitis do require utilization of broader spectrum antibiotics for a longer period of time.

Usually in most areas of the world, antibiotic / antimicrobial treatment of acute cystitis has been based upon utilization empirically of first-line options, second-line options, and third-line options but it is important for clinicians to know generally the antibiotic sensitivity patterns of the common causes of acute cystitis / urinary tract infection within their areas of practice because of the fact drug-resistant strains of organisms do develop in various parts of the world that could be different. Some clinicians had utilized one day empirical antimicrobial / antibiotic treatments, others had used 3 days treatment options and others had used one week treatment options. Perhaps with the knowledge of the antimicrobial / antibiotic sensitivity pattern of the area of the world a clinician is practicing perhaps a 3-days to 7 days treatment could be enough. Nevertheless, it is important for each clinician to assess his or her patient thoroughly based upon detailed clinical history taking and assessment and to manage each patient well based upon the diagnosis of the cause of the cystitis and the sensitivity pattern of any cultured organism. Prevention methods should be explained to each patient following assessment and management of each patient.

Keywords: Acute cystitis; escherichia coli; proteus; klebsiella; candida; cryptococcus; immune-compromised; schistosoma haematobium; adenovirus; chlamydia; mycoplasma; chemotherapy; radiotherapy; trauma; antibiotics; antimicrobials

Introduction

Acute cystitis is a common condition which tends to be encountered in all parts of the world and does manifest with urinary frequency, lower abdominal pain and or burning sensation on voiding. Diagnosis of acute cystitis has tended to be made based upon the symptoms of the patients, urine microscopy, culture and sensitivity. Acute cystitis has tended to be commonly encountered in young women who are within their reproductive ages as well as in older women. The most common bacterial agents that cause acute cystitis do include Escherichia Coli (E Coli), Proteus, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter species. Acute cystitis also does tend to be caused by Candida, or Cryptococcus with regard to immunocompromised individuals as well as by Schistosoma haematobium within Egypt and furthermore, acute cystitis could be caused by adenovirus, chlamydia, as well as by mycoplasma. Non-infectious causes of acute cystitis do include Chemotherapy, radiotherapy causing radiation cystitis, as well as trauma.

Escherichia Coli (E Coli) cases of acute cystitis, the mode of infection has tended to be by the faecal flora and in women acute cystitis has tended to be from the vaginal flora which have tended to be commonest immediate source for the infecting strain. Acute cystitis can be associated with complications including pyelonephritis if it is not treated well. Because of the development resistance to antibiotics and the causative agents of acute cystitis, it is important to ascertain the antibiotic and anti-microbial sensitivity pattern of the causative agents in order to choose the right medicament empirically as well as it is important to send urine specimens for culture and sensitivity before initiating treatment. Considering that clinicians globally have had varied experiences with regard to the management of acute cystitis, it is important to review the literature on all times of acute cystitis and its management in order to be up to date with the diagnosis and management of the disease. The ensuing article on various aspects of cystitis is divided into two parts: (A) Overview and (B) Miscellaneous narrations and discussions related to various studies/reports related to acute cystitis.

Methods

Internet databases were searched including Google; Google scholar; PUBMED; Yahoo; And AOL. The search words that were used included: Acute cystitis; Cystitis; Urinary Bladder Infections; Urinary Tract Infections. Fifty-one references were identified which were used to write the article which has been divided into two parts: (A) Overview and (B) Miscellaneous narrations and discussions related to various studies / reports related to acute cystitis.

Overview

Definition / general statements

• It has been iterated that a clinical diagnosis of acute cystitis usually tends to be made by the clinician based upon the obtaining a triad of manifestations including urinary frequency, lower abdominal pain and dysuria and that the dysuria could present as pain or burning upon micturition.

• It has also been documented that usually when a diagnosis of acute cystitis is made the diagnosis is made with no surgical specimen of the urinary bladder or urothelium, even though acute cystitis could be a finding in a urinary bladder or urothelial specimen which had been obtained for other purposes or during examination of specimen of the urinary bladder or urothelium during the process of autopsy examination.

• Epidemiology: It has been stated that cases of acute cystitis tend to be commonly encountered in young women who are within their reproductive ages and also that acute cystitis also tends to be diagnosed in older men as well as in older women.

• Sites: It has been iterated that acute cystitis has tended to affect the urinary bladder or the lower urinary namely the urethra.

• Aetiology: It has been iterated that the commonest bacterial agents that cause acute cystitis do include Escherichia Coli (E Coli), Proteus, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter species.

• It has additionally been iterated that acute cystitis also does tend to be caused by Candida, or Cryptococcus with regard to immunocompromised individuals as well as by Schistosoma haematobium within Egypt and furthermore, acute cystitis could be caused by adenovirus, chlamydia, as well as by mycoplasma.

• Furthermore, it has been documented that: non-infectious causes of acute cystitis, do include Chemotherapy, radiotherapy causing radiation cystitis; as well as trauma.

• It has been explained that with regard to Escherichia Coli (E Coli) cases of acute cystitis, the mode of infection has tended to be by the faecal flora and in women acute cystitis has tended to be from the vaginal flora which have tended to be commonest immediate source for the infecting strain.

• It has been iterated that the prevalence hypothesis had stipulated that the Escherichia coli strain for the acute cystitis could represent the most prevalent faecal / vaginal Escherichia coli clones of the individual or the special pathogenesis hypothesis has postulated that a distinctive, highly selected subset of the faecal / vaginal Escherichia coli population with enhanced virulence potential could be responsible for the development of acute cystitis [1,2].

Clinical Manifestations of Acute Cystitis

The ensuing summations have been made regarding the presentation of cases of acute cystitis:

• Some patients who have acute cystitis could be asymptomatic.

• Acute cystitis could also develop as ensuing obstruction of the lower urinary tract, cystocele or ensuing diverticula of the urinary bladder or urethra.

• Acute cystitis could lead to the subsequent development of pyelonephritis.

• Uncomplicated cases of acute cystitis tend to occur in otherwise healthy non-pregnant adult ladies.

• It has been iterated that: complicated cases of acute cystitis, tend to be associated with conditions which tend to increase the risk of treatment failure, such as upper urinary tract infection or drug resistant pathogen; and in such scenarios a broader spectrum anti-microbial treatment has been recommended to ensure successful treatment.

• It has been iterated that following treatment of acute cystitis the prognosis of acute cystitis tends to be excellent with resolution of symptoms usually within a period of 1 day to 2 days after treatment.

Treatment

The appropriate approach to the treatment of acute cystitis has been summated as follows:

• The suggested clinical algorithm for the treatment of acute cystitis is to treat empirically with antibiotics if there is evidence of 2 out of 3 variables present, dysuria, urine WBC > trace; Otherwise, the clinician should obtain urine for culture and to await the results of the urine culture and sensitivity.

• It has been recommended that complicated cases of acute cystitis should require treatment with a broader-spectrum antibiotics for a longer period of time.

Macroscopic (Gross) Examination Features of Acute Cystitis

The gross examination features of acute cystitis have been summated as follows:

• Macroscopy examination of the urinary bladder could demonstrate no evidence of gross vesical abnormalities.

• On rare occasions macroscopy examination of the urinary bladder in cases of acute cystitis could demonstrate vesical mucosa which could be hyperaemic with variable amount of exudate.

Microscopy histopathology examination findings

It has been iterated that in cases of acute cystitis, histopathology examination of the urinary bladder or urothelium of the urethra tend to demonstrate neutrophils [3].

Miscellaneous Narrations and Discussions from some Case Reports, Case Series and Studies Related to Acute Cystitis

Roger et al. undertook a meta-analysis of six double-blinded clinical trials in order to ascertain the risk factors that are associated with the bacteriological outcome in 3,108 women who were diagnosed as having developed acute cystitis. They iterated that eleven-antibiotic regimens were utilized with the inclusion of ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, norfloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin. The entry criteria for all of the studies were documented to be identical. With regard to 2,409 patients who had been defined to be valid for efficacy analysis, the pathogens were reported to include Escherichia coli which accounted for 78.6% of the pathogens, Staphylococcus saprophyticus which accounted for 4.4% of the pathogens, Klebsiella pneumoniae which accounted for 4.3% of the pathogens, Proteus mirabilis which accounted for 3.7% of the pathogens and other pathogens that amounted to 9% of the pathogens. Roger et al. iterated that the causative bacteria had been eradicated at the end of the treatment in 93% of the patients. The ensuing parameters were found to be associated with successful bacteriological outcome: not utilizing a diaphragm with a P value of P = -0041, treatment three days or longer than 3 days with a P value of = .0043, pathogen not “other” with a P value of = 0.043, duration of symptom being less than 2 days with a P value of = .0096, and African race with a P Value of P = .0147. Roger et al. also reported that Klebsiella pneumoniae with a P value of .0496 and “other” pathogens with a P value of P = .0018, were found to be associated with increased probability of bacteriological treatment failure.

Presence of pyuria equal to or greater than 10 white blood cells per high-power field was not to have correlated with the outcome and it was found to be inversely correlated with the finding of equal to or greater than 10 to the power 5 bacterial colony-forming units per mL of urine with a P value of less than .001. Roger et al. [4] iterated that their large database had identified new parameters that are associated with treatment outcomes of acute cystitis and does call into question current clinical trial guidelines. Hooton et al. stated that the cause of acute uncomplicated cystitis tends to be determined upon the basis of cultures of voided midstream urine, but few data do guide the interpretation of such results, especially when gram-positive bacteria grow. With regard to the methods of their study, Hooten et al. reported that women whose ages had ranged from 18 years to 49 who had symptoms of cystitis had provided specimens of midstream urine, after which they collected urine by means of a urethral catheter for culture (catheter urine). Hooten et al. compared microbial species and colony counts in the paired specimens. Hooten et al. iterated that the primary outcome was a comparison of positive predictive values and negative predictive values of organisms that had grown in the midstream urine, with the presence or absence of the organism in catheter urine that was utilized as the reference. Hooten et al. reported the following results:

• The analysis of 236 episodes of cystitis in 226 women had yielded 202 paired specimens of midstream urine and catheter urine which could be evaluated.

• Cultures were positive for uropathogens in 142 catheter specimens which amounted to 70% of cases, 4 of which had more than one uropathogen, and in 157 midstream specimens that amounted to 78% of cases.

• The presence of Escherichia coli within midstream urine was found to be highly predictive of bladder bacteriuria even at very low counts, with a positive predictive value of 102 colonyforming units (CFU) per millilitre of 93% (Spearman›sr=0.944).

• On the contrary, within midstream urine, enterococci that amounted to within 10% of cultures, and group B streptococci which was found in 12% of cultures, were found not to be predictive of bladder bacteriuria at any colony count (Spearman’s r=0.322 for enterococci and 0.272 for group B streptococci).

• Out of 41 episodes in which enterococcus, group B streptococci, or both were found within midstream urine, Escherichia coli grew from catheter urine cultures in 61%.

Hooten et al. [5] made the following conclusion:

• Cultures of voided midstream urine in healthy premenopausal women who had acute uncomplicated cystitis accurately demonstrated evidence of bladder Escherichia. coli but not of enterococci or group B streptococci, which were often isolated with Escherichia. coli but they appear to rarely cause cystitis by themselves.

Gupta et al. iterated that context Guidelines for the management of acute uncomplicated cystitis in women that recommend empirical treatment in properly selected patients do rely upon the predictability of the agents that cause cystitis and knowledge of their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Gupta et al. assessed the prevalence of as well as the trends in antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens that cause well-defined episodes of acute uncomplicated cystitis in a large population of women. With regard to the design of the study, Gupta et al. reported cross-sectional survey of antimicrobial susceptibilities of urine isolates that were collected during a 5-year period (January, May, and September 1992- 1996). They also reported that the patients were women whose ages had ranged between 18 years and 50 years and who had an outpatient diagnosis of acute cystitis. Gupta et al. stated that their main outcome measures included: The proportion of uropathogens demonstrating in vitro resistance to selected antimicrobials; trends in resistance over the 5-year study period.

Gupta et al. summarised the results as follows:

• Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus saprophyticus were the commonest uropathogens, which accounted for 90% of the 4342 urine isolates they had studied.

• The prevalence of resistance among Escherichia coli and all isolates combined was greater than 20% for ampicillin, cephalothin, and sulfamethoxazole in each year they had studied.

• The prevalence of resistance to trimethoprim and trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole had increased from more than 9% in 1992 to more than 18% in 1996 among Escherichia coli, and from 8% to 16% among all isolates combined.

• There was a statistically significant increasing linear trend with regard to the prevalence of resistance from 1992 to 1996 among Escherichia coli and all isolates combined to ampicillin (P<.002), and to cephalothin, trimethoprim, and trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole (P<.001).

• On the contrary, the prevalence of resistance to nitrofurantoin, gentamicin, and ciprofloxacin hydrochloride was found to be 0% to 2% among Escherichia coli and less than 10% among all isolates combined, and this did not change significantly during the 5-year period.

Gupta et al. [6] made the ensuing conclusions:

• While the prevalence of resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ampicillin, and cephalothin did increase significantly among uropathogens that cause acute cystitis, resistance to nitrofurantoin and ciprofloxacin had remained infrequent.

• These in vitro susceptibility patterns need to be considered along with other factors, including: efficacy, cost, and cost-effectiveness in selecting empirical treatment for acute uncomplicated cystitis in women.

• Moreno et al. [2] stated the following: Previous epidemiological assessments of the prevalence versus special pathogenicity hypothesis for the pathogenesis of urinary tract infection (UTI) in women might have been confounded by underlying host population differences between women might have been confounded by underlying host population differences between women who have urinary tract infection (UTI) as well as healthy controls and had not considered the clonal complexity of the faecal Escherichia coli population of the host.

• In their reported study, 42 women who had acute uncomplicated cystitis did serve as their own controls for an analysis of the causative Escherichia coli strain and the concurrent intestinal Escherichia coli population.

• They assessed the clonality among the urine isolate and 30 faecal colonies per subject by repetitive-element PCR and macro- restriction analysis.

• Each unique clone had undergone PCR-based phylotyping and virulence genotyping.

• Molecular analysis resolved 109 unique clones (4 urine-only, 38 urine-faecal, and 67 faecal-only clones.

• Urine clones had exhibited a significantly higher prevalence of group B2 in comparison with faecal-only clones (69% versus 10%, P<0.001) and higher aggregate virulence scores (mean, 6.2 versus 2.9, P <0.001).

• Within multi-level regression models for the prediction of urine clone status, significant positive predictors had included: group B2, 10 individual virulence traits, the aggregate virulence score, faecal dominance, relative faecal abundance, and (unique to the present study) a pauci-clonal faecal sample.

• In summary, within the faecal Escherichia coli populations of women who had acute cystitis, pauci-clonality, clonal dominance, virulence, and group B2 status were closely intertwined.

• Phylogenetic group B2 status and/or associated virulence factors could promote faecal abundance and pauci-clonality, thereby contributing to upstream steps in the pathogenesis of urinary tract infection (UTI).

• This relationship would suggest a possible reconciliation of the prevalence and special-pathogenicity hypothesis or postulate.

McIsaac et al. stated that Background Guidelines for the treatment of acute cystitis do support empirical antibiotic treatment; nevertheless, up to half of symptomatic women do tend to have negative urine culture results. McIsaac et al. determined whether empirical therapy does lead to unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions in women who have symptoms of acute cystitis. With regard to the methods of their study, McIsaac et al. reported that a cohort of 231 women who were defined as females aged 16 years and older than 16 years who had presented to family their physicians’ offices with symptoms of cystitis had undergone a standardized clinical assessment, urine dip testing, and culture. McIsaac et al. stated that they had compared recommendations for urine testing and antibiotic treatment under 3 empirical strategies with observed physician management and a logistic regression model for the outcomes of antibiotic prescriptions, urine culture testing, and unnecessary antibiotics, defined as a prescription where the subsequent urine culture was negative. McIsaac et al. summarised the results as follows:

• There were 123 positive urine cultures that amounted to 53.3%.

• Physicians had prescribed antibiotics for 186 women that amounted to 80.9% of the patients, of whom 74 (that amounted to 39.8% of the patients were culture negative.

• Utilization of unnecessary antibiotic was similar for 2 guidelines that recommended empirical antibiotic therapy without testing for pyuria (41.4% and 40.6%).

• Treating women who had classic cystitis symptoms and pyuria would have decreased unnecessary antibiotic utilization (26.2%; P = .02) but it had resulted in fewer women with confirmed urinary tract infection receiving immediate antibiotics (66.4% vs 91.8% usual care; P<.001).

• A derived prediction model which does incorporate testing for pyuria and nitrites would also have reduced unnecessary antibiotic use (27.5%; P = .03); however, more women who have confirmed urinary tract infection would have received immediate antibiotics (81.3%; P = .01).

McIsaac et al. [7] made the ensuing conclusions.

• Empirical antibiotic therapy of acute cystitis in women without testing for pyuria does promote unnecessary antibiotic utilization.

• A simple decision rule does provide for prompt therapy of infected women while reducing antibiotic overuse and unnecessary urine testing.

Hooten et al. undertook a study in order to ascertain the efficacy, safety, and costs associated with four different 3-day regimens for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis in women. Hooton et al. undertook a prospective randomized trial with a cost analysis related to women who had acute cystitis and who had attended a student health centre. With regard to interventions, Hooten et al. reported that treatment had included 3-day oral regimens of trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole, 160 mg/800 mg twice daily, macrocrystalline nitrofurantoin, 100 mg four times daily, cefadroxil, 500 mg twice daily, or amoxicillin, 500 mg three times daily. Hooten et al. summarized the results as follows:

• Six weeks after treatment, was received by 32 patients which had amounted to 82% of 39 women who had undergone treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and were cured in comparison with 22 women that amounted to 61% of 36 women who were treated with nitrofurantoin at P=.04 versus trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole, 21 women that amounted 66% of 32 women who were treated with cefadroxil at P=.11 versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and 28 women that amounted to 67% of 42 women who were treated with amoxicillin at P=.11 versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

• Persistence of significant bacteriuria was documented to be less common with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole that occurred in 3% of cases and cefadroxil that occurred in 0% of cases in comparison with nitrofurantoin which occurred in 16% of cases at P=.05 versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and amoxicillin which occurred in 14% of cases at P=.11 versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

• Persistence of bacteriuria was noted to be associated with amoxicillin-resistant strains in the amoxicillin group but nitrofurantoin- susceptible strains within the nitrofurantoin group.

• Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was found to be more successful in the eradication of Escherichia coli from rectal cultures soon after treatment and from urethral and vaginal cultures at all follow-up visits in comparison with the other treatment regimens.

• Adverse effects were reported by 16 patients that amounted to 35% out of 46 patients who had received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, which was reported in 18 patients that amounted to 43% of 42 patients who had received nitrofurantoin, 12 patients that amounted to 30% out of 40 patients who had received cefadroxil, and 13 patients that amounted to 25% of 52 patients who had received amoxicillin.

• The mean costs per patient were noted to be less with trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole that amounted to $114) and amoxicillin that amounted to $131 in comparison with nitrofurantoin that amounted to $155 and cefadroxil that amounted to $155.

Hooten et al. [8] made the ensuing conclusions:

• A 3-day regimen of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is more effective and less expensive in comparison with 3-day regimens of nitrofurantoin, cefadroxil, or amoxicillin for the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis in women.

• The increased efficacy of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is likely related to its antimicrobial effects against Escherichia coli in the rectum, urethra, and vagina.

Hooten et al. compared the safety and efficacy of a single 400 mg dose of ofloxacin, ofloxacin (200mg) once daily for 3 days, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole(160:800mg) twice per day for 7 days for and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for the therapy of acute uncomplicated cystitis (urinary tract infection) in women, or the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis (urinary tract infection (UTI) in women. They reported the results as follows:

• At 5 weeks after the treatment, 35 out of 43 patients that amounted to 81% of the 43 patients who were treated with single-dose ofloxacin, 40 out of 45 patients that amounted to 89% of the 45 treated patients with 3 days of ofloxacin, and 41 patients out of 42 patients that amounted to 98% of 42 treated patients with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were cured (P=0.03, single-dose ofloxacin group versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole group).

• Re-treatment for symptomatic recurrent UTI was given to 7 patients out of 43 patients that amounted to 16% of 43 patients who were initially treated with single-dose ofloxacin, 3 patients out of 45 patients that amounted to 7% of the 45 patients who were initially treated with 3 days of ofloxacin, and 0 of 42 patients who were initially treated with trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole (P=0.01, single-dose ofloxacin group versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole group).

• There was the finding of a trend in each of the three treatment groups toward an association between persistent or recurrent episodes of significant bacteriuria and a history of UTI in the preceding year and with diaphragm use.

• Ofloxacin was found to be more effective in comparison with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole with regard to eradicating Escherichia coli from rectal cultures during or soon after the treatment; however, there were no differences at later follow- up visits.

• Adverse effects related to the medications were found to be equally common among the three treatment groups.

Hooten et al. [9] made the following conclusions:

• They had concluded that single-dose ofloxacin was less effective in comparison with 7 days of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for treatment of uncomplicated cystitis in women, whilst the 3-day ofloxacin regimen and the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole regimen were found not to be significantly different with regard to efficacy.

• The majority of cases of acute cystitis in young healthy women tend to be effectively treated with utilization of conventional oral antimicrobial agents such as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or nitrofurantoin.

• Ampicillin and sulfonamides had become less reliable in such cases in view of the high prevalence of resistance to these agents among common uropathogens.

• The new fluoroquinolone antimicrobial agents, of which ofloxacin is one, had also been shown to be effective for the therapy of cystitis.

• Whilst these agents have tended not to be considered the therapy of choice for uncomplicated cystitis, they often tend to be utilized in patients who are intolerant of conventional agents, who have resistant pathogens, or in whom the presence of a complicating factor is more likely.

• Single-dose or 3-day regimens of antimicrobial agents are becoming increasingly popular for the therapy of uncomplicated cystitis in view of the fact that, in comparison with conventional regimens, they tend to be as effective, and they tend to be associated with fewer adverse effects, better compliance, and lower cost.

• Nevertheless, there are no published data related to the utilization off the new fluoroquinolones in single-dose regimens for the therapy of uncomplicated cystitis within the United States of America.

• They had therefore compared the safety and efficacy of ofloxacin in a single-dose regimen with a regimen of once-daily doses of ofloxacin for 3 days and with a conventional 7-day regimen of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis in women.

• They had also undertaken a study of the effects of these regimens on rectal and perineal colonization with coliforms.

Hooten et al. compared the safety and efficacies of ofloxacin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis in women who had been enrolled within a multi-centre study. Hooten et al. combined data from three centres which were reported in this article because the study design and the study populations were noted to be identical, and the patients had been enrolled within an 18-month period. Hooten et al. reported the following:

• The cure rates for evaluable patients 4 weeks after treatment were high for all regimens that had included: ofloxacin, 200 mg twice daily for 3 days, in 22 out of 25 patients that amounted to 88% of patients that were cured; ofloxacin 200 mg, twice daily for 7 days, among whom 42 out of 49 patients that amounted to 86% were cured; ofloxacin 300 mg, twice daily for 7 days, in which 25 of 25 patients that amounted to 100% were cured; and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 160/800 mg, twice daily for 7 days, in which 46 out of 52 patients that amounted to 88% were cured.

• Ofloxacin was effective in comparison with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the eradication of Escherichia coli from rectal cultures during and 1 week after treatment.

• Both ofloxacin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole did markedly reduce vaginal colonization with Escherichia coli during and 4 weeks after therapy.

• Emergence of resistant coliforms in rectal flora was identified 5 patients that amounted to 19% out of 27 patients who had been treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole but none of 50 ofloxacin-treated patients who were studied at P = 0.004).

• Adverse effects were found to be equally common among the four treatment groups. Hooten et al. [10] concluded that 3 to 7 days of ofloxacin is as safe and effective as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for the therapy of uncomplicated cystitis in women and that ofloxacin had effectively reduced the faecal and vaginal reservoirs of coliforms in such patients.

Gossius and Vorland compared the efficacy of a single-dose, 4 tablets of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) with that of a 3-day and 10-day treatment with TMP-SMX, 2 tablets twice daily, in 464 female out-patients who had symptoms that denoted acute, uncomplicated urinary tract infection (UTI). Gorssius and Vorland reported the following:

• Three hundred and twenty-one, (321) patients that amounted to 70% of the patients, had significant bacteriuria.

• The effect of treatment effect could be assessed in 279 women.

• Comparable results had been obtained with the 3 regimens 2, and 6 weeks, following treatment.

• Eradication of the initial organism had occurred in 96% of the patients who had a single-dose treatment, in 96% to 94% with a 3-day treatment, and in 98% with a 10-day course of treatment.

• The incidence of adverse reactions was found to be significantly greater in patients who had undergone treatment with a 10- day which occurred in 28% of patients than in those who had undergone treatment with a single-dose which occurs in 5% of patients, or 3-day regimen which occurred in 9% of patients at p < 0.01.

Gossius and Vorland [11] concluded that their study suggests that short treatment regimens for uncomplicated UTI in women are as effective as and cause fewer side-effects than the conventional 10-day chemotherapy.

Rafalsky et al. iterated that uncomplicated acute cystitis is one of the commonest bacterial infections in adults and that the percentage of women who have at least one episode of acute cystitis had been estimated to be between 40% to 50%. They also stated that Quinolones are recommended for the treatment of acute cystitis in regions where the level of resistance to other antimicrobials namely co‐trimoxazole is high. Nevertheless, the efficacy, safety and tolerance of quinolones needed to be investigated. Rafalsky et al. compared the efficacy, safety and tolerance of different quinolones in women who had uncomplicated acute cystitis.

Rafalsky et al. searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, in The Cochrane Library Issue 3, 2003), MEDLINE (1966 ‐ September 2003), EMBASE (1988 ‐ September 2003), reference lists of articles and abstracts from conference proceedings without language restriction. Reference lists of urology, infectious diseases and nephrology textbooks, review articles and relevant studies. With regard to their selection criteria, Rafalsky et al. undertook a randomised and quasi‐randomised controlled trials in which they compared two or more different quinolones in women who were 16 years old or older than 16 years and who had uncomplicated acute cystitis. With regard to the collection and analysis of data, Rafalsky et al. stated that two reviewers had independently assessed trial quality and extracted data. They performed Statistical analyses with utilization of random effects model and the results were expressed as risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Rafalsky et al.

• They had identified 11 studies which had enrolled 7535 women.

• There were no significant differences with regard to clinical or microbiological efficacy between quinolones.

• Photosensitivity reactions were found to be more frequently observed for sparfloxacin in comparison with ofloxacin.

• Any adverse event, adverse events that caused withdrawal, skin adverse events, photosensitivity reactions were found to be more common for lomefloxacin in comparison with norfloxacin.

• Any adverse event, adverse drug reactions, central nervous system (CNS) adverse events were found to be more common for ofloxacin in comparison with ciprofloxacin.

• CNS adverse events and insomnia were noted to be more often reported for rufloxacin in comparison with pefloxacin.

• Adverse drug reactions were noted to have occurred frequently for ofloxacin in comparison with levofloxacin.

• Insomnia was found to have been reported more frequently for enoxacin in comparison with ciprofloxacin.

Rafalsky et al. [12] concluded that: They had not found any significant differences in clinical or microbiological efficacy between quinolones but some differences in occurrence and spectrum of quinolone safety.

Kavatha et al. had included one hundred and sixty-three (163) women who had uncomplicated acute lower urinary tract infections in a multi-centre randomized study which had compared cefpodoxime- proxetil, one 100-mg tablet twice daily, with trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole, one double-strength tablet [160/800 mg] twice daily, for 3 days. With regard to the results of the study, they reported the following:

• A total of 30 women in both arms had been excluded from the study for various reasons.

• At 4 days to 7 days after the discontinuation of treatment, 62 of 63 recipients that amounted to 98.4% who had received cefpodoxime- proxetil and 70 of 70 patients that amounted to 100%, who had received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole were clinically cured and had demonstrated bacteriological eradication, respectively.

• At 28 days following treatment, 48 of 55 patients that amounted to 87.3% of the patients and 43 of 50 patients that amounted to 86% who had received cefpodoxime-proxetil as well as 51 of 60 that amounted to 85% of recipients and 42 out of 50 patients that amounted to 84% of patients who received trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole were clinically cured and had demonstrated bacteriological eradication, respectively.

• Independently of the prescribed regimen, a significant difference (P < 0.001) in failure rates was found only for patients who had a previous history of three or more episodes of acute cystitis per year.

• With the exception of one patient in the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole arm who had discontinued treatment because of gastrointestinal pain, both antimicrobials were well tolerated. Kavatha et al. [13] concluded that cefpodoxime-proxetil treatment for 3 days was as safe and effective as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 3 days for the treatment of uncomplicated acute cystitis in women.

Gupta et al. literated that there is a paucity of data regarding the efficacy of nitrofurantoin for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis in regimens that are shorter than 7 days and that evidence-based utilization of this drug is increasingly important as trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance among uropathogens increases. Gupta et al. assessed the efficacy of nitrofurantoin versus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, in 338 women who were aged between 18 years and 45 years who had acute uncomplicated cystitis and who were randomized to open-label treatment with either trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole, 1 double-strength tablet twice daily for 3 days, or nitrofurantoin, 100 mg twice daily for 5 days. The main outcome measure was clinical cure 30 days after treatment. The secondary outcomes included clinical and microbiological cure rates 5 to 9 days following treatment and, for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole– treated women, clinical cure stratified by the trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole susceptibility of the uropathogen.

Gupta et al. summarized the results as follows:

• The clinical cure was achieved in 79% of the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole group and in 84% of the nitrofurantoin group, for a difference of 5% at 95% confidence interval, −13% to 4%.

• The clinical and microbiological cure rates at the first follow-up visit were also equivalent between the 2 groups of patients.

• In the trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole arm of patients, 7 out of 17 women that amounted to 41% with a trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole– non-susceptible isolate did have a clinical cure in comparison with 84% of women with a trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole– susceptible isolate (P < .001).

Gupta et al. [14] concluded that a 5-day course of nitrofurantoin is equivalent clinically and microbiologically to a 3-day course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and it should be considered as an effective fluoroquinolone-sparing alternative for the treatment of acute cystitis in women.

Colgan et al. stated that urinary tract infections are the commonest bacterial infections in women and that majority of urinary tract infections are acute uncomplicated cystitis. Colgan et al. [15] also stated the following:

• The identifiers of acute uncomplicated cystitis are frequency and dysuria in an immunocompetent woman of childbearing age who does not have any comorbidities or urologic abnormalities.

• Physical examination typically tends to be normal or positive for supra-public tenderness.

• A urinalysis, but not urine culture, has been recommended with regard to making the diagnosis of acute uncomplicated cystitis.

• Guidelines do recommend three options for first-line treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis which include: fosfomycin, nitrofurantoin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole within regions where the prevalence of Escherichia coli resistance does not exceed 20 percent.

• Beta-lactam antibiotics, amoxicillin/clavulanate, cefaclor, cefdinir, and cefpodoxime are not recommended for initial treatment because of concerns about resistance.

• Cultures of urine cultures have been recommended in women who have suspected pyelonephritis, women who have symptoms which do not resolve, or which do recur within two to four weeks following completing treatment, and women who manifest with atypical symptoms.

Kurt and Naber [16] stated that urinary tract infection (UTI) has been classified as uncomplicated if it does occur in a patient who has a structurally and functionally normal urinary tract and that acute uncomplicated cystitis tends to be observed mainly in women. They also stated the:

• Urinary tract infection does need; nevertheless, to be differentiated depending upon whether it does occur in premenopausal, postmenopausal or pregnant women.

• Only a small number of 15-years to 50 years old, otherwise healthy men do suffer acute uncomplicated cystitis.

• In premenopausal, non-pregnant women, single-dose antimicrobial therapy generally tends to be generally less effective in comparison with the same antibiotic utilized for a longer duration. Nevertheless, most antimicrobial agents that are given for 3 days tend to be as effective as those that are given for longer duration, and adverse events tend to be found more often in cases of longer treatment.

• Trimethoprim (or co-trimoxazole) could be recommended as first-line empirical treatment only in communities that have resistance rates of uropathogens to trimethoprim of less than 10% to 20%. Otherwise, fluoroquinolones have been recommended.

• Alternative treatments do include: fosfomycin trometamol or β-lactams, such as second- or third-generation oral cephalosprins or pivmecillinam, particularly when fluoroquinolones are contraindicated or a high proportion of greater than 10% of Escherichia coli strains within the community are already resistant to fluoroquinolones, as in Spain, for example.

• Recurrent UTIs tend to be common among young, healthy women, although, they generally tend to have anatomically and physiologically normal urinary tracts.

• The ensuing prophylactic antimicrobial treatment options have been recommended: (i) utilization of long-term, low-dose prophylactic antimicrobials taken at bedtime; (ii) post-coital prophylaxis for women in whom episodes of infection are associated with sexual intercourse.

• Other prophylactic treatment options are not as yet as effective as antimicrobial prophylaxis.

Pitkajarvi et al. [17] reported that in an open randomized study, Pivmecillinam (Selexid; CAS 32886-97-8) had been studied by general practitioners in 345 female patients who had uncomplicated acute cystitis and that out of the bacteriologically evaluated 299 patients, 151 patients had undergone treatment for three days with two tablets of Pivmecillinam 200 mg three times per day. and 148 patients for seven days with one tablet three times per day. There were no significant differences with regard to the bacteriological effect between the two regimens. They summarized the results as follows:

• In the 3-day group 91% and 88% of the patients were cured at the first and the second control; in the 7-day group 94% of the patients and 95% of the patients, respectively.

• There was no significant difference with regard to the total clinical effect, either.

• The adverse reactions, usually gastrointestinal disturbances, had occurred in 10% of the 3-day group and in 11% of the 7-day group (N.S.).

• Pivmecillinam therapy in acute cystitis in women was equally effective whether it was given for three or seven days, with the same total frequency of adverse reactions for the two regimens.

Naber stated that short-term treatment, including single-dose treatment, including single-dose up to 3-day courses, could be considered the treatment of choice in pre-menopausal women who develop acute uncomplicated cystitis, in view of similar effectiveness, better tolerance and compliance, as well as lower cost as with conventional treatment. Naber et al. stated the following:

• Many studies with utilization of trimethoprim alone or in combination with a sulfonamide, usually sulphamethoxazole, and fluoroquinolones with moderately long half-lives, such as ciprofloxacin, enoxacin, lomefloxacin, and ofloxacin, had indicated that the results obtained with a single dose could be inferior to those with utilization of a 3-day course, hence, that the latter could be a better treatment.

• Longer treatment had not been considered to be necessary.

• On the contrary, fluoroquinolones with longer half-lives, such as fleroxacin, perfloxacin, and rufloxacin, as single-dose treatment could be as effective as other standard treatment regimens.

• Fosfomycin tromentamol might also be suitable for single-dose treatment.

• Agents that had not been demonstrated to be effective in any of these short-term regimens should no longer be utilized for the treatment of acute cystitis.

Gupta et al. they had collected four hundred and fifty-two urine isolates from women who had acute uncomplicated cystitis and a positive urine culture who had presented to a sexually transmitted disease clinic between 1989 and 1991, and 213 specimens were collected over a period between 1995 and 1997.

Gupta et al. summarised the results of their study as follows:

• The predominant species was Escherichia coli, which accounted for 68% of the isolates; other species included Staphylococcus saprophyticus which accounted for 8% of the isolates, Group B streptococci which accounted for 7% of the cases, Proteus spp., which accounted for 6% of the isolates, Klebsiella spp., which accounted for 4% of the isolates and Enterococcus spp., which accounted for 3% of the isolates.

• More than 10% of the Escherichia. coli isolates were found to be resistant to ampicillin, cephalothin, tetracycline and trimethoprim– sulfamethoxazole (TMP–SMX ) during both study periods, with the greatest increase in resistance to ampicillin and TMP/SMX between the two periods.

• Six hundred and four urinary tract infection isolates, including 83% Escherichia. coli, 7% Staphylococcus. saprophyticus, 3% Klebsiella spp. 2% Proteus spp., 2% enterococci, 1% Enterobacter spp. and 2% other organisms, had been collected from women who had acute cystitis and who had attended a university student health service during 1995.

• Among Escherichia. coli isolates, 25% were found to be resistant to ampicillin, 24% were found to be resistant to tetracycline and 11% were resistant to TMP–SMX.

• Resistance to fluoroquinolones was essentially absent among gram-negative pathogens.

Gupta et al. [18] iterated that continued evaluation of susceptibility patterns of pathogens that cause acute uncomplicated cystitis to traditional as well as new antimicrobials in well-defined populations is necessary in order to ascertain the optimal empirical treatment.

Biswas et al. iterated that a high prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among urinary isolates in the Garhwal region of Uttaranchal did exist. Biswas et al. undertook a study to identify the most appropriate antibiotic for empirical treatment of community-acquired acute cystitis upon the basis of local antimicrobial sensitivity profile. Biswas et al. undertook a prospective clinical-microbiological study which had included all clinically diagnosed patients with community acquired acute cystitis who had attended a tertiary care teaching hospital over a period of three years. With regard to the methods and materials of the study, Biswas et al. reported the following:

• Clean-catch midstream urine specimens, from 524 non-pregnant women who had community-acquired acute cystitis, had been subjected to semi-quantitative culture and antibiotic susceptibility by the Kirby- Bauer disc diffusion method.

• A survey was also undertaken on 30 randomly selected local practitioners, to know the prevalent prescribing habits in this condition.

• With regard to the statistical analysis of the study, the difference between the susceptibility rates of Escherichia. coli isolates to Nitrofurantoin and the other commonly prescribed antibiotics were analysed by application of the z test for proportion.

Biswas et al. summarized the results as follows:

• Three hundred and fifty-four, (354) specimens which amounted to 67.5% of the specimens had yielded significant growth of Escherichia coli > 35% of the urinary E. coli isolates which were resistant to the fluoroquinolones, which were noted to be the most commonly utilized empirical antibiotics in acute cystitis.

• Resistance was minimum against Nitrofurantoin that was found in 33 cases that amounted to 9.3% of cases, and Amikacin in 39 cases that amounted to 11.0% of cases. Greater than (>) 80% of the fluoroquinolone-resistant strains were found to be sensitive to Nitrofurantoin.

Biswas et al. [19] made the following conclusions:

• The best in vitro susceptibility profile in their study had been shown by Nitrofurantoin and a significantly high proportion of the urinary Escherichia coli isolates had already developed resistance to the currently prescribed empirical antibiotics, viz. the fluoroquinolones.

• In view of the in vitro susceptibility patterns that had been demonstrated, a transition in empirical therapy did appear imminent.

Grigoryan et al. stated that the updated 2010 Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines had recommended 3 first-line treatments for uncomplicated cystitis including: nitrofurantoin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), and fosfomycin, while fluoroquinolones (FQs) had remained as second-line agents. Grigoryan et al. assessed guideline concordance for antibiotic choice and treatment duration after introduction of the updated guidelines and they also studied patient characteristics associated with prescribing of specific antibiotics and with treatment duration. Gregoryan et al. utilized the Epic Clarity database (electronic medical record system) to identify all female patients who were aged 18 years or older than 18 years, and who had uncomplicated cystitis in 2 private family medicine clinics in the period of 2011–2014. For each eligible visit, Gregoryan et al. extracted type of antibiotic prescribed, the duration of treatment, and patient and visit characteristics. Gregoryan et al. summarized the results as follows:

• They had included 1546 visits.

• Fluoroquinolones were the commonest antibiotic class that was prescribed which accounted for 51.6% of the prescriptions, followed by nitrofurantoin which accounted for 33.5% of the prescriptions, TMP-SMX which accounted for 12.0% of the prescriptions, and other antibiotics that accounted for 3.2% of the prescriptions.

• A significant trend had occurred toward increasing TMP-SMX and toward decreasing nitrofurantoin utilization.

• The duration of majority of prescriptions for TMP-SMX, nitro-furantoin, and FQs was longer than guidelines recommendations and longer durations were prescribed for these agents in 82%, 73%, and 71% of the prescriptions, respectively.

• No patient or visit characteristic was found to be associated with utilization of specific antibiotics.

• Older age and presence of diabetes mellitus were found to be independently associated with longer treatment duration.

Gregoryan et al. [20] made the ensuing conclusions:

• They found low concordance with the updated guidelines for both the choice of drug and duration of therapy for uncomplicated cystitis in primary care.

• Identification of barriers to guideline adherence and designing interventions to decrease overuse of FQs could help preserve the antimicrobial efficacy of these important antimicrobials.

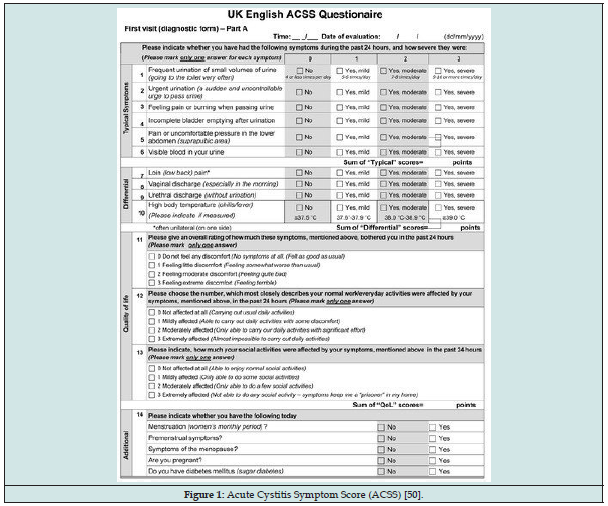

Alidjanov et al. undertook a study which was aimed at the development as well as establishing of validation of a simple and standardized self-reporting questionnaire for acute uncomplicated cystitis (AUC) assessing typical and differential symptoms, quality of life and possible changes after therapy in female patients with AUC. Alidjanov et al. [21] undertook a literature research, development and evaluation of the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score (ACSS), an 18-item self-reporting questionnaire including (a) six questions about ‘typical’ symptoms of AUC, (b) four questions regarding differential diagnoses, (c) three questions on quality of life and (d) five questions on additional conditions which may affect therapy. The ACSS was evaluated in 286 women whose mean age was 32.3 ± 12.3 years, in the Russian and Uzbek language. Measurements of reliability, validity, predictive ability and responsiveness were undertaken. Alidjanov et al. summarized the results as follows:

• Cronbach’s alpha for the ACSS was 0.89, split-half reliability was 0.92 and correlation between halves was 0.85. Mann-Whitney test demonstrated significant difference scores of the ‘typical’ domain between patients and controls (10.75 vs. 2.02, p < 0.001).

• The optimal threshold score was found to be 6 points, with a 94% sensitivity and 90% specificity to predict AUC.

• The symptom score had significantly decreased when comparing before and after treatment (10.7 vs. 2.1, p < 0.001).

Alidjanov et al. [21] made the following concluding statements:

• The new validated ACSS is accurate enough and it could be recommended for clinical studies and practice for initial diagnosis as well as monitoring treatment of AUC.

• Evaluation in other languages was in progress.

Alidjanov et al. [22] undertook a study which had aimed to re-evaluate the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score (ACSS). The ACSS is a simple and standardized self-reporting questionnaire for the diagnosis of acute uncomplicated cystitis (AC) for the assessment of typical and differential symptoms, quality of life, and possible changes after treatment in female patients with AC. The article of Alidjanov et al. included literature research, development and evaluation of the ACSS, an 18-item self-reporting questionnaire including (a) six questions about “typical” symptoms of AC, (b) four questions regarding differential diagnoses, (c) three questions on quality of life, and (d) five questions on additional conditions that may affect therapy. The ACSS had been evaluated in 228 women whose mean age was 31.49 ± 11.71 years in the Russian and Uzbek languages. Measurements of reliability, validity, predictive ability, and responsiveness had been undertaken. They reported the following findings:

• Cronbach’s alpha for ACSS was 0.89, split-half reliability was 0.76 and 0.79 for first and second halves, and the correlation between them was 0.87. Mann-Whitney U test demonstrated a significant difference in scores of the “typical” symptoms between patients and controls (10.50 versus. 2.07, p < 0.001).

• The optimal threshold score was 6 points, with a 94% sensitivity and 90% specificity to predict AC. The “typical” symptom score decreased significantly when comparing before and after therapy (10.4 and 2.5, p < 0.001).

• They re-evaluated Russian and Uzbek ACSS are accurate enough and can be recommended for clinical studies and practice for initial diagnosis and monitoring the process of the treatment of AC in women.

• Evaluation in German, UK English, and Hungarian languages was also undertaken and in other languages evaluation of the ACSS was in progress.

Grigoryan et al. iterated that there was a lack of evidence on the optimal approach for the treatment of acute cystitis in women who have diabetes mellitus. Gregoryan et al. undertook an outpatient database study to compare the management of women with and without diabetes mellitus and to assess the effect of treatment duration on early and late recurrence. Grigoryan et al. utilized the EPIC Clarity database (electronic medical record system) to identify all female patients aged 18 years or older than 18 years who had developed acute cystitis in two family medicine clinics and a urology department. An index case was defined as the first cystitis episode during the study period between 2011 and 2014, with follow-up data of at least 12 months. Grigoryan et al. defined recurrence as a Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) episode, plus a new prescription for an antibiotic, between 6 and 29 days (early), or between 30 days and 12months (late). Gregoryan et al. [23] summarized the results as follows:

• They had included 2327 visits for cystitis representing 1845 unique patients.

• Women who had diabetes mellitus and acute cystitis were less likely to receive urinary tests to work up cystitis, and received significantly longer treatment courses of antibiotics.

• There was a higher risk for the development of early recurrence in women who had treatment duration longer than 5 days (odds ratio 2.17, 95% confidence interval 1.07–4.41) in multivariate analyses.

• Longer treatment was found not to be associated with late UTI recurrence.

• Presence of diabetes mellitus, and Charlson comorbidity score were found to be independent determinants of late recurrence.

Grigoryan et al. made the following conclusions:

• Longer treatment of cystitis was found not to be associated with lower recurrence rates.

• This does call into question whether many episodes of diabetic cystitis may be managed with a short course of antibiotics, as for uncomplicated disease.

Savini et al. reported a case in which Escherichia fergusonii, which was stated to be an emerging pathogen in various types of infection which as associated with cystitis in a 52-year-old woman. The offending strain of Escherichia was found to be multi-drug resistant. Despite in vitro activity, beta-lactam treatment had failed because of a lack of patient compliance with treatment. Savini et al. [24] stated that their reported case had confirmed the pathogenic potential of Escherichia fergusonii.

Johnson et al. stated that within-household transmission of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli (ExPEC) could contribute to the pathogenesis of urinary tract infection (UTI), but this was poorly understood. Johnson et al. reported a woman who had acute UTI, 4 human household members who cohabitated with her, and the family›s pet dog who had undergone prospective longitudinal surveillance for colonizing Escherichia. coli for 7 weeks to 9 weeks after the woman›s UTI episode. Unique clones were resolved by random amplified polymorphic DNA and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis. Virulence genes, phylogenetic group, and O types were defined by PCR. Johnson et al. undertook comparisons with reference strains utilizing random amplified polymorphic DNA profiling. Johnson et al. summarized the results as follows:

• Serial faecal and urine samples from the 6 household members had yielded 7 unique Escherichia coli clones out of which 4 were ExPEC and 3 of which were non-ExPEC.

• For 3 clones, extensive among-host sharing was evident in patterns which had suggested host-to-host transmission.

• The mother’s UTI clone, which represented Escherichia. coli O1:K1:H7, was found to be the clone that was most extensively shared in 5 hosts, including the dog, and most frequently recovered in 45% of the samples and at all 3 time points.

• The other 3 ExPEC clones had corresponded with Escherichia. coli O6: K2:H1, O1:K1:H7, and O2: F10, F48.

Johnson et al. [25] concluded that:

• Escherichia. coli clones, including ExPEC, could be extensively shared among human and animal household members in the absence of sexual contact and in patterns suggesting host-tohost transmission.

Hooten et al. stated that acute uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection (cystitis) is one of the commonest and easily cured bacterial infections in women. Nevertheless, increasing antibiotic resistance does complicate its treatment by increasing patient morbidity, costs of reassessment and re-treatment, rates of hospitalization, and utilization of broader-spectrum antibiotics. Hooten et al. [26] made the ensuing summations:

• Guidelines that had been published in 1999 by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) had recommend trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) as first-line treatment for acute cystitis—noting; nevertheless, that resistance to this agent was increasing [27].

• Even though public health authorities had increasingly recommended narrow-spectrum antibiotics for the treatment of community-acquired respiratory and urinary tract infections (UTIs) whenever possible, concerns regarding antibiotic resistance had resulted in a burgeoning utilization of fluoroquinolones.

• Over the preceding few years, utilization of fluoroquinolones (overall and for UTIs) in ambulatory care had dramatically increased, whereas utilization of TMP-SMX for UTIs had decreased [28-30].

• If trends in the utilization of fluoroquinolones do continue, this crucial class of drugs would likely become less effective, not only for the treatment of respiratory and urinary tract infections, but also for the treatment of foodborne infections, sexually transmitted diseases, and health care—associated infections.

• Prompted, in part, by the well-documented increase in the utilization of fluoroquinolones for the treatment of upper respiratory tract infections and the evolving resistance of uropathogens to TMP-SMX, the Alliance for the Prudent utilization of Antibiotics had convened a scientific meeting of experts on 10 June 2003 in order to review the current knowledge of the epidemiology of uncomplicated UTIs, examine the adequacy of the current therapeutic guidelines, discuss options that would improve empirical; UTI therapy and minimize antimicrobial resistance, and consider how resistance should be factored into the development of professional guidelines for treatment of UTIs.

Ernst et al. stated that even though acute cystitis is a common infection in women, the impact of this infection and its treatment upon women’s quality of life (QOL) had not been previously described. Ernst et al. evaluated QOL in women who had been treated for acute cystitis, and they described the relationship between QOL, clinical outcome and adverse events of each of the interventions utilized in the study. The study of Ernst et al. was a randomized, open-label, multi-centre study of two family-medicine clinics in Iowa. The study involved one-hundred-fifty-seven women with clinical signs and symptoms of acute uncomplicated cystitis. Among the patients, fifty-two patients received trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 1 double-strength tablet twice daily for 3 days, 54 patients received ciprofloxacin 250 mg twice daily for 3 days and 51 patients received nitrofurantoin 100 mg twice daily for 7 days. The measurements of the study included measurements of quality of life (QOL) which was assessed at the time of enrolment of the patients as well as at 3 days, 7 days, 14 days, and 28 days following the initial consultation of the patients. The QOL was measured with utilization of a modified Quality of Well-Being scale, which is a validated, multi-attribute health scale. Ernst et al. assessed the clinical outcome by telephone interview on days 3, 7, 14 and 28 with utilization of a standardized questionnaire to assess resolution of symptoms, compliance with the prescribed regimen, and occurrence of adverse events. Ernst et al. summarized the results as follows:

• Patients who had experienced a clinical cure had significantly better QOL at days 3 (p = 0.03), 7 (p < 0.001), and 14 (p = 0.02) in comparison with patients who failed treatment.

• While there was no difference in QOL by treatment assignment, patients who had experienced an adverse event had lower QOL throughout the study period.

• Patients who had undergone treatment with ciprofloxacin appeared to have experienced adverse events at a higher rate which amounted to 62% in comparison with those patients who had undergone treatment with TMP/SMX which occurred in 45% of the patients and nitrofurantoin which was experienced by 49% of patients; nevertheless, the difference was found not to be statistically significant (p = 0.2)

Ernst et al. [31] made the ensuing conclusions:

• Patients who had experienced cystitis had an increase in their QOL with treatment.

• Those patients who experienced clinical cure had greater improvement in QOL in comparison with patients who had failed therapy.

• While QOL was improved by treatment, those patients who had reported adverse events had lower overall QOL in comparison with those patients who did not experience adverse events.

• Their study was important in that it had suggested that both cystitis and antibiotic treatment can affect QOL in a measurable way.

Abrahamian et al. stated that the association of in vitro resistance with bacteriological, clinical, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) outcomes for acute uncomplicated cystitis is not clear. Abrahamian et al. conducted a prospective study of women who were aged between 18 years and 40 years and who had acute uncomplicated cystitis symptoms for equal to or longer than 7 days and who subsequently had a growth of Enterobacteriaceae sp. and who initially received trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) and phenazopyridine. Abrahamian et al. undertook telephone follow- up evaluation of the patients’ clinical cure at 1 day to 3 days and in-person follow-up evaluating clinical, bacteriological, and HRQoL outcomes at 3 days to 7 days and at 4 weeks to 6 weeks following their treatment. Abrahamian et al. summarized the results as follows:

• An Enterobacteriaceae sp. was isolated in 139 patients that amounted to 96.5% of the patients and 25.2% of them were TMP/SMX-resistant.

• At 1 day to 3 days post-treatment, clinical cure had occurred in 56 out of 81 patients which amounted to 69.1% of the patients and 14 out of 31 cases which amounted to 45.2% of cases with susceptible and resistant strains, respectively (difference 23.9%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.5–46.4%).

• At 3 days to 7 days post-treatment, bacteriological cure had occurred in 70 out of 73 cases which amounted to 95.9% of cases and 15 out of 25 cases which amounted to 60% of cases with susceptible and resistant strains, respectively (difference 35.9%; 95% CI, 13.5–58.3%).

• Sustained clinical cure rates at 3 days to 7 days and 4 weeks to 6 weeks post-treatment were 65.4% and 56.8% with susceptible strains, and 45.2% and 45.2% with resistant strains, respectively.

• The HRQoL scale assessing role limitations due to physical health problems was found to be lower in TMP/SMX-resistant versus TMP/SMX-susceptible infections, with twice as many hours of missed activities reported (mean, 18.4 versus. 9.1 h).

• Differences in HRQoL had appeared to be largely related to differences in the clinical cure rates.

Abrahamian et al. [32] concluded that among women who had undergone treatment for acute uncomplicated cystitis with TMP/SMX, in vitro TMP/SMX resistance was associated with lower bacteriologic and clinical cure rates and had greater impact upon the time lost from daily activities in comparison with those patients who had TMP/SMX-susceptible infections.

Nicolle [33] stated the following:

• Empirical antimicrobial therapy for acute cystitis in women does require continuing reassessment as the antimicrobial susceptibility of community isolates of Escherichia coli evolves.

• Current recommendations for 3 days trimethoprim or trimethoprim/ sulphamethoxazole had been compromised by increasing resistance of community Escherichia coli to these agents.

• Fluoroquinolones are an alternate 3-day therapy option; nevertheless, increasing resistance was being reported from some countries, and widespread community utilization could promote resistance, limiting effectiveness of these agents for more serious infections.

• Alternate treatment regimens that had been supported by recent clinical trials had suggested pivmecillinam to be administered twice daily for 7 days is as effective as 3 days of quinolone treatment, while microbiological cure is 80% with 3 days treatment twice daily, and 90% with 3 days therapy thrice daily.

• Nitrofurantoin which is administered for 7 days does have a cure rate of 80% to 85%.

• Fosfomycin trometamol as a single dose does have cure rates of 75% to 85%.

• All these agents tend to be effective, but a compromise in efficacy or duration of therapy in comparison with current 3-day regimens may have to be considered.

Alidjanov et al. stated that the Uzbek version of the Acute Cystitis Symptom Score (ACSS) was developed as a simple self-reporting questionnaire in order to improve upon the diagnosis and treatment of women who have acute cystitis (AC) and that they had undertaken some work which had the aim of validating the ACSS in the German language. With regard to materials and methods, Alidjanov et al. stated the following:

The ACSS consisted of 18 questions in four subscales which included:

(1) typical symptoms, (2) differential diagnosis, (3) quality of life, and (4) additional circumstances. Translation of the ACSS into German was undertaken based upon to international guidelines. For the validation process, 36 German-speaking women whose ages had ranged between 18 years and 90 years, with and without symptoms of AC, were included in their study. Classification of participants into two groups was undertaken with patients or controls which was based upon the presence or absence of typical symptoms and significant bacteriuria (≥ 10(3) CFU/ml). Statistical evaluations of reliability, validity, and predictive ability were undertaken. ROC curve analysis was undertaken in order to assess sensitivity and specificity of ACSS and its subscales. The Mann-Whitney’s U test and t-test were utilized to compare the scores of the groups. Alidjanov et al. summarized the results as follows:

• Out of the 36 German-speaking women who were aged: 40 ± 19 years, 19 were diagnosed as having AC which constituted the patient group, and 17 women served as controls. Cronbach’s α for the German ACSS total scale was 0.87. A threshold score of equal to or higher than 6 points in category 1 (typical symptoms) significantly predicted AC (sensitivity 94.7%, specificity 82.4%).

• There were no significant differences in ACSS scores in patients and controls in comparison with the original Uzbek version of the ACSS.

Alidianov et al. [34] concluded that the German version of the ACSS had shown a high reliability and validity. Therefore, the German version of the ACSS could be reliably utilized in clinical practice and research for the diagnosis and therapeutic monitoring of patients who suffer from AC.

Rodhe et al. undertook a search for useful diagnostic tools to in order to discriminate between asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) and acute cystitis, and in their study, they compared urinary levels of cytokines/chemokines and leukocyte esterase in three groups of elderly subjects: those with acute cystitis, those with ASB, and those without bacteriuria. Their study was a comparative laboratory study which had included a total of 16 patients who had acute cystitis, 24 subjects who had ASB, and 20 controls without bacteriuria, all of whom were aged 80 years or older than 80 years. With regard to the main outcome measures, these included: Urinary levels of IL- 1β, TNF-α, IL-12, IL-18, CXCL1 (GRO-α), CXCL8 (IL-8), CCL2 (MCP- 1), IL-6, IL-10, and leukocyte esterase. Rodhe et al. summarized the results as follows:

• Urinary levels of CXCL1, CXCL8, and IL-6 were found to be significantly higher in acute cystitis patients in comparison with in the ASB group.

• The sensitivities and specificities for CXCL8, IL-6, and leukocyte esterase to discriminate between acute cystitis and ASB were 63% (95% CI 36–84) and 96% (95% CI 77–100) (cut-off > 285 pg/mg creatinine), 81% (95% CI 54–95) and 96% (95% CI 77–100) (cut-off > 30 pg/mg creatinine), and 88% (95% CI 60–98) and 79% (95% CI 57–92) (cut-off > 2, on a scale of 0–4), respectively.

Rodhe et al. [35] made the following conclusion:

• The results had indicated that measurement of urinary cytokines, and also leukocyte esterase, when utilizing a cut-off value > 2, could be useful with regard to clinical practice to discriminate between symptomatic and asymptomatic urinary tract infections in the elderly.

• A combination of IL-6 and leukocyte esterase could even be more useful.

• This does need to be evaluated in prospective studies related to the diagnosis and treatment of urinary tract infections in an elderly population.

McIsaac et al. stated that in a previous study, utilization of a decision aid based upon 4 clinical items would have reduced unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions for acute cystitis by 30% in comparison with the usual physician care. McIsaac et al. assessed the decision aid in a different population of females who had been seen in community-based practice. McIsaac et al. reported that between April 7, 2002, and March 20, 2003, 225 Canadian family physicians had recorded clinical findings, urine dip test results, and treatment decisions for 331 females who were suspected to have cystitis. The number of decision aid items present was determined for each patient, and the sensitivity and specificity of decision aid recommendations for empirical antibiotics were determined utilizing the gold standard of a positive urine culture result (≥102 colony-forming units per millilitre). Total antibiotic prescriptions, unnecessary prescriptions (for negative culture results), and recommendations for urine cultures were determined and compared with physician management. McIsaac et al. summarized the results as follows:

• Three of the original decision aid variables that included: dysuria, the presence of leukocytes [greater than a trace amount], and the presence of nitrites [any positive]) were found to be associated with having a positive urine culture result (P ≤ .001); however, 1 variable (symptoms for 1 day) was not (P = .96).

• A simplified decision aid that incorporated the 3 significant variables (empirical antibiotics without culture if ≥2 variables present; otherwise obtain a culture and wait for results) had a sensitivity of 80.3%, which was found in 167 out of 208 patients and a specificity of 53.7% in 66 out of 123.

• Following decision aid recommendations would have reduced antibiotic prescriptions by 23.5%, unnecessary prescriptions by 40.2%, and urine cultures by 59.0% in comparison with physician care (P < .001 for all).