Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2644-1373

Research ArticleOpen Access

Origin and Distribution of Goats in World and India: An Approach Which was Till Date Neglected Volume 3 - Issue 1

Somenath Ghosh1*, Rupam Kumari2

- 1Assistant Professor and Coordinator, Department of Zoology, Rajendra College, Jai Prakash University, India

- 2Guest Faculty, Department of Zoology, Rajendra College, Jai Prakash University, India

Received:February 24, 2023; Published:March 06, 2023

Corresponding author:Somenath Ghosh, Assistant Professor and Head, Department of Zoology, Rajendra College, Jai Prakash University, Bihar, India

DOI: 10.32474/LOJPCR.2023.03.000154

Abstract

Goats were the earliest animals to be domesticated during neolithic times along with the cultivation of cereals. Following the domestication of cattle and pigs, draft animals such as horses and asses were also domesticated. The Harappa toys contain representations of goats. Two seals from Mohenjo-daro show a wild bezoar goat with enormous, curled horns and a bearded domestic male goat with side-spreading horns. The Gaddi goat, which greatly resembles the ancestral wild goat, was used as a beast of burden in the mountains and is still used in the Himalayan region of India for carrying salt and food grains. In the Indo- Gangetic plains, goats were among the first ruminants to be domesticated in 2000 BC. The wild goat (Capra hircus) was the chief ancestral stock from which the various breeds of domestic goats originated. Then they had a wide distribution from the barren hills of Baluchistan to the western Sind. The domestication of the goat species, their movement and distribution across continents have resulted in the evolution of nearly 570 breeds throughout the world which includes pure and cross-bred goat population. But unfortunately, till date goat breeds and their cosmopolitan populations are regarded as one of the most neglected ones in terms of scientific studies, literature and experimentation.

Keywords:Breeds, capra hircus, domestication, goats, neglected

Introduction

Till date the available data regarding the goat breeds suggests that out of 570 breeds; 187 (33%) breeds are found in Europe, 146 (26%) breeds in Asia and Pacific region and 89 (16%) breeds in Africa [1]. All these totally comprise 422 breeds. But the exact data for the remaining 48 breeds are under controversy. Speculatively they are either wild breeds or on the verge of extinction having only a few numbers of individuals remaining [2]. Goats are the most helpful friends to poor people because of their prominent role and contribution in the developing countries’ economy. Goats contribute to the subsistence of small holders and landless rural poor. Goats are short day breeder ruminant and taxonomically belonging to the class mammalia order Artiodactyla, sub-order Ruminantia, family Bovidae and genus, Capra. Goats are cosmopolitan and found across all agro-ecological environments and nearly in all livestock production systems [3]. Goats are suitable for very extensive to highly mechanized production systems [4]. India is bestowed with 17% of total world’s goat population comprised of 21 recognized and many non-descript local breeds. Small ruminants are useful in many ways because of their role in income generation, food supply (meat and milk), and financial security for the poor goatherds in rural areas [5].

The expansion of human population coupled with urbanization has created a crisis of food materials and demand for meat per capita increased in recent years. Even if it is continued to produce livestock and their products at the current rate, there will be a lag between the production and demand of bio-food for expanding human population. In the tropics and sub-tropics, the interest in goat production has grown only in recent years. In the bioindustry, goats are underutilized and poorly understood resources even more under estimated in terms of veterinary research. A fair understanding of goat physiology and its industrial capabilities and economic outputs will be helpful in increasing the overall productivity of tropical goat farming systems. Despite of the large goat population, diversity and their economic significance, the caprine research in India particularly to the indigenous goats has been neglected by ruminant researchers. Although small ruminants are a major component of the livestock sector in most parts of the world including India, yet the information about goats and its physiology is very limited and fragmented. The importance of small ruminants for meat production in the tropics was well recognized by [6]. However, small-ruminant production has some constraints and disease, which are associated with high mortality, decline in productivity and reproductive performance and even public health concerns [7].

Origin of Indian Goats

Goats are among the earliest animals domesticated by humans. The most recent genetic analysis confirms the archaeological evidence that the wild Bezoar ibex of the Zagros Mountains are the likely origin of almost all domestic goats today. Neolithic farmers began to herd wild goats for easy access to milk and meat, primarily, as well as for their dung, which was used as fuel, and their bones, hair, and sinew for clothing, building, and tools. The earliest remnants of domesticated goats dating 10,000 years before present are found in Ganj Dareh in Iran. Goat remains have been found at archaeological sites in Jericho, Choga Mami Djeitunand Çayönü, dating the domestication of goats in Western Asia at between 8,000 and 9,000 years ago. Goats were the first wild herbivores to be domesticated in the Near East around 11,000 years ago at the beginning of the revolutionary transition from hunter‐gatherer to agriculture‐based societies. Ever since that time, goats have fulfilled a vital economic, cultural and religious role in many human civilizations. A collaborative research effort that integrates genetics and archaeology has vastly expanded our ability not only to detect the context, locations and timing of initial goat domestication but also to trace the migratory trajectories used by humans to spread this farm animal worldwide. The successful geographical diffusion and exponential growth of goat populations around the world clearly demonstrate the remarkable adaptability of this ruminant species to extreme climates and difficult terrains and offer an excellent opportunity to assess the rise and fall of human migratory and commercial networks during historical times.

The domestication of animals was carried out during Neolithic times along with the cultivation of cereals. First goats and sheep, second cattle and pigs, and finally draft animals such as horses and asses were domesticated. The wild goat (Capra hircus), the chief ancestral stock from which the various breeds of domestic goats have been derived, is found in the barren hills of Baluchistan and the western Sind. In northeast Quetta, it is replaced by markhor (Capra falconeri), also found in Turkestan, Afghanistan, Baluchistan and Kashmir. The Circassia goat is said to be the descendent of the markhor. By far the most important variety is the bezoar goat (Capra hircus aegagrus), which ranges from the Sind in the east through Iran and Asia Minor to Crete and the Cyclades in the west, although in many parts of this area it has disappeared. From Iran it extends into Russian Turkestan and the Caucasus, and into western Asia Minor. There are many wild varieties of sheep (Ovis orientalis vignei) in the mountains from Afghanistan to Armenia, and they are probably the ancestors of the domesticated sheep of India as well as of Arabia. The inhabitants of Mohanjo-daro and Harappa already possessed domesticated sheep. Though sheep were probably first domesticated in the mountains of Iran, Turkestan and Baluchistan, we find them early in history, and they served a useful purpose in the economies of the Mesopotamian and northern Indian civilizations. They provided milk, meat and clothing for the inhabitants of the cold north [8].

Distribution of Goats in Middle East and Asia Minor

Population size and trends

The global population of wild goats has not been estimated. Although the species ranges vary widely, it is probably extremely rare or absent in much of its mapped range. In some places it is clearly decreasing rapidly. However, there is also evidence of localized population recovery when adequate protection is in place. The population trend across its range is likely to be a significant decrease, estimated at more than 30% over three generations. There is an urgent need for updated information on the status of this species. Specific information on country-level abundance is as follows:

a) Afghanistan No estimates of population numbers are available, but the species is probably now very rare in this country. It is probably confined to the Hazarajat and Uruzgan mountains in central Afghanistan, including the arid Feroz Koh and Siyah Koh in the headwaters of the Hari Rud, Farah Rud, Helmand and Arghandab rivers. However, no animals were observed by FAO or WWF survey teams in the 1970s, but horns and skulls were occasionally seen at shrines and grave sites. One captive animal seen in 1975 in a private zoo in Kandahar was reputedly caught in the nearby mountains. The species had probably been reduced to a small portion of its former range by the late 1970s. Its current status in the country is unknown.

b) Caucasus The species is represented by the nominate subspecies (C. a. aegagrus) which inhabits, here, mainly forested areas, so no accurate census could be performed to date. The total population estimate for wild goat was between 3,500 and 4,000 individuals in the late 1980s, with 1,500 in the Greater Caucasus and the rest in the Caucasus Minor, where more than half (1,000 to 1,250) lived in the southern half of the Zangezur range. At the end of 1990s, 2,500 animals were estimated for Daghestan alone, but numbers were declining rapidly, by 50% in three years. The overall population trend for the nominate subspecies is negative, and in recent years the rate of decline has increased. Bezoar goat (Capra aegagrus) has been widely distributed in the mountains of the Caucasus and particularly Georgia. During the last century populations of bezoar goat dramatically decreased, mostly because of unregulated hunting and poaching. Presently, within boundaries of the Georgia, only small population survived in Khevsureti-Tusheti province of the East Greater Caucasus. Outside Georgia, the closest relatively healthy populations occur in Daghestan/Russian Federation (East Greater Caucasus, estimated number - 2000 individuals) and South Armenia-Nakhchyvan Autonomy of Azerbaijan (South-West Lesser Caucasus, estimated number - 2200-2500 individuals). Status of those populations was assessed in 2007-2008.

The distribution of Capra aegagrus aegagrus is in two separate parts. It occurs in forested areas along northern slopes of the Greater Caucasus Mountains from the Upper Argun River, in Chechen- Ingushetia and in Georgia, up to the headwaters of the Jurmut River in Daghestan, with an isolated population on the southern slopes of Mount Babadagh, Azerbaijan. It also occurs in the drier, more open habitats in the Caucasus Minor Mountains in both Azerbaijan and Armenia, south and east of Sevang Lake, namely the Shakhdagh, Mrovdagh, Karabakh, Gegam, Vardenis and Zangezur ranges, and on the Delidagh massif. Borjomi-Kharagauli NP is located in the eastern part of West Lesser Caucasus Mountain chain covering 76,000 ha of temperate broad-leaf and coniferous forests, and alpine grasslands. During initial WWF project on bezoar goat reintroduction in the NP, implemented in 2003-2006, nine individuals (six females and three males) were transported from Armenia and placed in enclosure. Experts from Armenia provided instructions for keeping animals. Later the enclosure was enlarged. Presently, only five individuals survived: three from initial group (one female and two males) and two males born in enclosure.

c) Iran No estimates of total numbers are currently available. However, 1991 estimates are available for Golestan National Park - 2,500 animals, and for Alborz-Markazy Protected Area - 4,000 animals. The wild goat is widely distributed throughout Iran wherever large areas of rocky terrain are available. This includes not only mountainous areas, but also cliffs along the seashore, in deciduous forested areas of the north, and in areas of the central desert./p>

d) Iraq There are no population estimates, but the species is probably extremely rare, if it survives at all. If it still occurs in Iraq, it would most likely be found in the Zagros Mountains in the extreme north and along the northeastern border with Iran. Nothing is known of current distributions.

e) Pakistan Two subspecies occur: For Capra aegagrus blythi there is no overall population estimate. Most survive in small inaccessible areas in isolated populations. However, reasonable numbers are reported for the Dhrun and Hingol areas. Kirthar National Park probably contains the largest population of Sind wild goat in the country. In the Karchat Mountains, which are within Kirthar National Park, the population has increased from between 400 and 500 when the establishment park was established in 1973 to around 950 to 1,050. The adjacent Surjan-Sumbak-Eri-Hothiano Game Reserve contained another 900 to 1,100, resulting in a total estimate of 2,400 to 3,100 wild goats for Sind Province. For Capra aegagrus chialtanensis the single population totaled around 168 animals in 1975. Due to rigid protection following establishment of the National Park in 1980, the population had increased to 480 animals by 1990 but this improvement may not have continued.

There is an urgent need to updated information on the abundance of the wild goat in Pakistan. The present range of Sind wild goat (Capra aegagrus blythi) is the Baluchistan plateau and its foothills in South-western Pakistan. Populations are scattered on arid mountain ranges that are isolated by lowlands of southern Baluchistan and Sind. The range includes the low Mekran coastal range (District Gwadar), areas up to 3,250 individuals in the Kohi- Maran range south of Quetta (District Kalat), and also the Kirthar range (Districts of Dadu and Las Bela). The Chiltan goat (Capra aegagrus chialtanensis) was restricted in the early 1970s to four or five populations in the accessible mountain range (Chiltan, Murdar, Koh-i-Maran and Koh-i-Gishk ranges) South of Quetta. Today, these have been reduced, principally by uncontrolled hunting, to only one surviving population in the Hazarganji-Chiltan National Park (Districts of Quetta and Kalat).

f) Turkey It is declining in Turkey throughout its range, and the total population is believed to be less than 10,000 mature individuals, with no subpopulation larger than 1,000 mature individuals. The wild goat ranges widely in Turkey, east from the Datca peninsula, through the Taurus and Anti-Taurus mountains in the mountainous regions of south-eastern, eastern and northeastern Anatolia.

g) Turkmenistan Korshunov, whose data are the most reliable, estimated that the total population was up to 7,000 animals. The Turkmen wild goat (Capra aegagrus blythi) occurs in scattered populations in the central Kopet Dagh along the border between Turkmenistan and Iran and in the Large Balkhan (Bolshye) North of Nebit Dagh. It is not known whether this subspecies still inhabits the Small Balkhan.

h) Greece The Agrimi or Cretan Wild Goat (formerly classified as Capra aegagrus cretica) survives on the central and western parts of the Lefka Ori mountain range (Samaria National Forest Park and nearby gorges) of Crete. According to surveys 2004-2008, its population is decreasing. In 2007, it was estimated at 960-990 animals. Its status was evaluated as Vulnerable (D1+2) [9]. It was introduced in the 20th century to the islets of Thodorou, Dia (exterminated due to hybridization with Capra hircus), Aghii Pantes, Moni, Sapientza and Atalandi, and to the Mt Parnitha National Park (central Greece). The most recent assumption regarding its origin is that it comes from Wild Goat stock brought to Crete, approx., 8,000 years ago. Its genetic affinity to Capra hircus is explained as partial interbreeding with domestic animals through millennia (Geskos, 2013).

i) Lebanon The wild goat used to be relatively common in Barouk, the Ammiq Mountains and on Mount Harmon, northern Lebanon. However, by the early 1900s it was extinct in Lebanon.

j) Oman In 1963, a male was captured on the mountains near Masafi, 20 miles from Manama. It is possible that an unsuspected population survives in the Western Hajr of U.A.E./Oman [10].

k) Syria Wild goat was reported in northern Syria, in the mountains north of Dimasq, and must once have occurred in the western mountains as well. However, it is now believed to be extinct.

Indian Goat Breeds, their Distribution and Morphological Charactersn

Definition of Breed

Breed is a population of a species originated from the same descent and having similar general body shape, colors, structure and characters which produced offspring with same characters.

Indian Goats can be Classified Under Four Major Heads

a) Milch Breeds

Indian: Jamunapari, Mehsana, Sirohi, Surti and Zalawadi

Exotic: Sannen, Alpine, Anglo-nubion and Toggenburg

b) Mutton Breeds

Black Bengal, Assam Hill Goats, Chegu, Ganjam and Malbari.

c) Dual purpose Breeds

Osmanabadi, Barberi, Marwari, Beetal and Kutchi

d) Hair/Fleece Breeds

Angora and Pashmina

Classification Based on Agro-Ecological Region

a) Northern temperate region

Breeds : Distribution

Gaddi : Himachal Pradesh Uttar Pradesh

Changthangi : Ladakh above 4000 m.

Chegu : Himachal Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh

b) North-Western Arid and Semi-arid region

Breeds : Distribution

Sirohi : Rajasthan and Gujarat

Marwari : Rajasthan and Gujarat

Jhakrana : Rajasthan

Beetal : Punjab and Haryana

Barbari : Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan

Jamunapari : Uttar Pradesh

Mehsana : Gujarat

Gohilwadi : Gujarat

Zalawadi : Gujarat

Surti : Gujarat

Kutchi : Gujarat

c) Southern region

Breeds : Distribution

Sangamneri : Maharastra

Osmanabadi : Maharastra

Kanni Adu : Tamil Nadu

Malabari : Kerala

d) Eastern region

Breeds : Distribution

Ganjam : Orissa

Bengal : West Bengal, Assam, Manipur, Tripura,

Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya

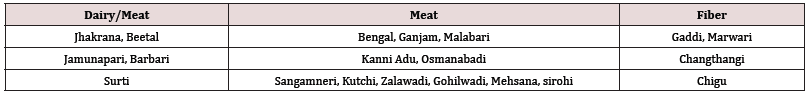

(Table 1) The north India has the largest number of goats’ i.e., approximately 29 million which is about 43% of the total goat population of the country. Some important breeds are Beetal, Barbari, Jamunapari, Merwari, Sirohi, Jhakrana, Mehsana, Gohilwari, Zalawadi, Kutchi and Surti. Most of the better dairy goat breeds (Jamunapari, Beetal, Barbari and Mehsana) are found in this region.

.Conclusion

With this brief review we just tried to encompass on different breeds and varieties of goats spread throughout the world and India. But further in-depth genetic studies are arrested to focus more on their varieties.

References

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet Tieulent J, et al. (2015) Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 65: 87-108.

- Morsalin S, Yang C, Fang J, Reddy S, Kayarthodi S, et al. (2015) Molecular Mechanism of β-Catenin Signaling Pathway Inactivation in ETV1-Positive Prostate Cancers. J Pharm Sci Pharmacol 2: 208-216.

- Rubin MA, Demichelis F (2019) The Genomics of Prostate Cancer: A Historic Perspective. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 9: a034942.

- Fang J, Xu H, Yang C, Morsalin S, Kayarthodi S, et al. (2014) Ets Related Gene and Smad3 Proteins Collaborate to Activate Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Mediated Signaling Pathway in ETS Related Gene-Positive Prostate Cancer Cells. J Pharm Sci Pharmacol 1: 175-181.

- Rao VN, Papas TS, Reddy ES (1987) erg, a human ets-related gene on chromosome 21: Alternative splicing, polyadenylation, and translation. Science 237: 635-639.

- Fang J, Huali Xu, Kayarthodi S, Fujimura Y, Yang C, et al. (2014) Molecular mechanism of activation of TGF-β signaling pathway in prostate cancers. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Pharmacology 1: 82-85.

- Reddy ES, Rao VN, Papas TS (1987) The erg gene: a human gene related to the ets oncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84: 6131-6135.

- Jané Valbuena J, Widlund HR, Perner S, Johnson LA, Dibner AC, et al. (2010) An oncogenic role for ETV1 in melanoma. Cancer Res 70: 2075-2084.

- Mahendraraj K, Sidhu K, Lau CSM, McRoy GJ, Chamberlain RS, Smith FO (2017) Malignant Melanoma in African Americans: A Population-Based Clinical Outcomes Study Involving 1106 African American Patients from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Result (SEER) Database (1988-2011). Medicine (Baltimore) 96: e6258.

- Miller JR, Hocking AM, Brown JD, Moon RT (1999) Mechanism and function of signal transduction by the Wnt/beta-catenin and Wnt/Ca2+ pathways. Oncogene 18: 7860-7872.

- Larue L, Luciani F, Kumasaka M, Champeval D, Demirkan N, et al. (2009) Bypassing melanocyte senescence by beta-catenin: a novel way to promote melanoma. Pathol Biol (Paris) 57: 543-547.

- Gasi Tandefelt D, Boormans J, Hermans K, Trapman J (2014) ETS fusion genes in prostate cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 21: R143-152.

- Made A, Dits NF, Boormans JL, van der Kwast TH, van Dekken H, et al. (2008) Truncated ETV1, fused to novel tissue-specific genes, and full-length ETV1 in prostate cancer. Cancer Res 68: 7541-7549.

- Hermans KG, van der Korput HA, van Marion R, van de Wijngaart DJ, Ziel van der Made A, et al. (2008) Truncated ETV1, fused to novel tissue-specific genes, and full-length ETV1 in prostate cancer. Cancer Res 68: 7541-7549.

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, Thompson JF, Atkins MB, et al. (2009) Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 27: 6199-6206.

- Ward Peterson M, Acuña JM, Alkhalifah MK, Nasiri AM, Al Akeel ES, et al. (2016) Association Between Race/Ethnicity and Survival of Melanoma Patients in the United States Over 3 Decades: A Secondary Analysis of SEER Data. Medicine (Baltimore) 95: e3315

- Mehra R, Dhanasekaran SM, Palanisamy N, Vats P, Cao X, et al. (2013) Comprehensive Analysis of ETS Family Members in Melanoma by Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization Reveals Recurrent ETV1 Amplification. Transl Oncol 6: 405-412.

- Jiao Q, Bi L, Ren Y, Song S, Wang Q, Wang YS (2018) Advances in studies of tyrosine kinase inhibitors and their acquired resistance. Mol Cancer 19 17(1): 36.

- Bologna M, Vicentini C, Muzi P, Pace G, Angelucci A (2011) Cancer Multitarget Pharmacology in Prostate Tumors: Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Beyond. Curr Med Chem 18: 2827-2835.

- Lin JZ, Wang ZJ, De W, Zheng M, Xu WZ, et al. (2017) Targeting AXL overcomes resistance to docetaxel therapy in advanced prostate cancer. Oncotarget 8: 41064-41077.

- Yadav YR, Parihar V, Namdev H, Bajaj J (2016) Chronic subdural hematoma. Asian J Neurosurg 11: 330-342.

- Fortson WS, Kayarthodi S, Fujimura Y, Xu H, Matthews R, et al. (2011) Histone deacetylase inhibitors, valproic acid and trichostatin-A induce apoptosis and affect acetylation status of p53 in ERG-positive prostate cancer cells. Int J Oncol 39: 111-119.

- Guinney J, Wang T, Laajala TD, Winner KK, Bare JC, et al. (2017) Prediction of overall survival for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: development of a prognostic model through a crowdsourced challenge with open clinical trial data. Lancet Oncol 18: 132-142.

- Bologna M, Vicentini C, Muzi P, Pace G, Angelucci A (2011) Cancer Multitarget Pharmacology in Prostate Tumors: Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Beyond. Curr Med Chem 18: 2827-2835.