Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2641-1652

Research Article(ISSN: 2641-1652)

Giant Colonic Lipomas: Diagnostic Accuracy, Case Series and A Review of the Literature Volume 1 - Issue 3

Akingboye AA*, Ansari A, Dennis R, Hardy A and Menon M

- Department of General Surgery, Peterborough City Hospital, Bretton Gate, England

Received: August 06, 2018; Published: August 16, 2018

*Corresponding author: Akinfemi A Akingboye, Department General Surgery Peterborough City Hospital, Bretton Gate, Peterborough, England

DOI: 10.32474/CTGH.2018.01.000113

Abstract

Aim: Colonic lipomas (CL) are generally asymptomatic and are found incidentally during colonoscopy, colonography or surgery for other conditions. Symptoms often correlate with the size of the lipoma; lipomas larger than 4 cm in size become symptomatic in 75% of patients and they are described as Giant colonic lipoma (GCL). GCL may cause bleeding, obstruction, mimic large polyps, and can create a diagnostic dilemma. We review the clinical management of a series of four GCL patients.

Method: Following a series of unusual presentations and management of patients with GCL; we decided to review CT colonography performed for patients not unsuitable and or unable to complete colonoscopy over a 4-year period. Furthermore, we described the clinical presentations and management outcomes from the 4-case series.

Results: A total of 3775 CT colonographies were performed between Jan 2011 – Dec 2015, with 174 (4.6%) cases of reported CL, of which 0.002% were identified as GCL. 116 CL patients were females (66%), with a mean age of 77 years. With more than 80% located in the right colon. From the case series analysed; four patients had GCL. Two patients presented as acute large bowel obstruction secondary to colonic intussusception on CT scan. Both required emergency hemi-colectomies. The other two presented with changes in bowel habit. One required an elective laparoscopic colotomy and the other was resected endoscopically.

Conclusion: CL can be confidently diagnosed on CT colonography and do not require any specialised imaging or endoscopic assessment for histologically purposes. Endoscopic removal of GCL is feasible and can be performed safely when the right skill set, and experience is available. However, surgical resection remains the main stay treatment for obstructive GCL.

Keywords: Colonic Lipoma; Giant Colonic Lipoma; CT Colonography; Endoscopy; Laparoscopy

Abbreviations: CL: Colonic Lipomas; GCL: Giant Colonic Lipoma; CT: Computed Tomography; CRC: Colorectal Cancer

Introduction

Lipomas of the digestive tract are rare and most often found incidentally during a colonoscopy, computed tomography (CT)/ Colonography (CTC) scan, surgery, or autopsy [1-3]. Lipomas of the colon were first reported by Bauer in 1757 and are most often located in the ascending colon near the Cecum [4]. Lipomas are non-epithelial, benign, fatty tumors that can be found throughout the gastrointestinal tract, although they are most frequently seen in the colon. Approximately 90% of Colonic lipomas (CL) are located in the submucosa; the remainder of these tumors are subserosal or intramucosal in origin. The reported incidence of CL ranges from 0.2% to 4.4% [5]. CL are more common in women than in men, with a predilection for the right colon in women and the left colon in men. The mean age of patients with CL falls within the sixth decade. These fatty tumors are rarely greater than 2 cm in size and are often asymptomatic. The patients with CL greater than 2 cm in size commonly presents with abdominal pain, hemorrhage, features of bowel obstruction, mimic large polyps, and can create a diagnostic dilemma. CL that grow more than 4 cm in size are referred to as giant colonic lipoma (GCL), which can lead to obstruction and intussusception requiring surgical or endoscopic resection [3].

Reporting of CL is not a priority for radiologist in the grand scheme of the demand on their time as it relates to reporting accurately on colorectal cancer (CRC), however, its good practice to report on other lesions greater than 5mm in the colon particular when the colon is not assessable by colonoscopy. CT colonography (CTC) has been shown to have a good percentage patient test characteristics in detecting CRC and large polyps. There are very few studies to date that reports on the detection accuracy of CL/GCL from CTC, the polyp detection rate is often an extrapolation from the sensitivity and specificity of CRC studies [6]. This review was conducted to evaluate the incident of reported CL from our routine CTC practice for patients who are unsuitable for colonoscopy and in addition described the variability in the management of GCL in our series.

Method and Materials

Following a series of unusual presentations and management of patients with GCL, we decided to retrospectively review all our CTC performed over a 4-year period January 2011- December 2015. CTC was usually performed as an alternative to colonoscopy for a group of patients who are either too frail to undergo colonoscopy, or there was an attempted failed colonoscopy whilst colorectal cancer remained highly suspicious and would not be excluded without further imaging. The clinical presentations, images, MDT outcomes and histology reports for the four cases were retrieved and analysed. The CT colonography was performed according to the local departmental protocol. In brief, a non-cathartic bowel preparation was used to reduce patient discomfort. Preparation started a day before CTC, patient was placed on low-fibre diet and four sachets of 50ml moviprep (total 200 ml) was given. Examinations were performed using a low dose protocol with 40 or 32 reference mAs on two 64-slice CT scanners. Patients were scanned in the supine and prone position. A muscle relaxant, 20 mg of butylscopolamine bromide was injected immediately prior to insufflation of the colon. A flexible balloon-tipped rectal catheter (20 French gauge) was inserted to insufflate approximately 3 litres of CO2 gas into the colon, using an automated insufflator. No intravenous contrast medium was administered. Due to the restricted bowel regime and the presence of tagged stool, a primary 2D axial evaluation (primary window setting 1500, 2250 HU) was carried out with 3D problem solving for the detection of polyps.

This was performed on a workstation with specialised software. Lesions were measured at the multiplanar reformatted (MPR) setting that showed the maximal diameter of the detected lesion. For each lesion the location, morphology and size was carefully documented. Only lesions equal and or greater than 5 mm that the observer reported with a >50% probability was considered positive. The initial report was done by two advanced gastrointestinal radiographer who performed the procedure and was then vetted by a consultant radiologist for final approval. Quality of bowel preparation was also rated by each observer and if the bowel preparation was judged insufficient for evaluation by the two observers, the procedure was repeated with a different bowel preparation. We retrieved all the clinical records of the 4 patients managed for GCL and we described the clinical presentations and management outcomes in greater detail.

Case Series

Case 1

75 years female. Two GLC were detected during routine bowel screening on colonoscopy; mid transverse and the other in the sigmoid. They are large and nearly fill the lumen of the colon measuring about 50mm each. The sigmoid GCL appeared to have intussuscepted. The MDT advised CT colonoscopy for further clarification of the lesion; as they mimicked a malignant tumor. CT scan confirmed two synchronous CL at the transverse colon (45mm) and proximal sigmoid (75mm) respectively. A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed and the 2 GCL were excised as colotomy.

Case 2

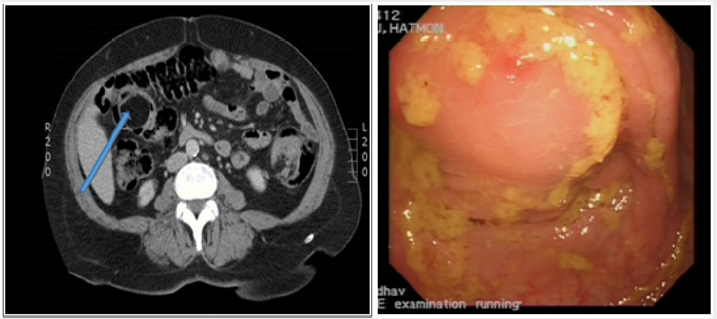

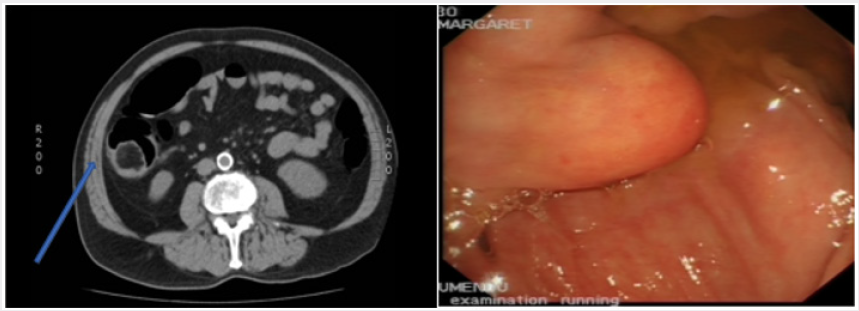

Figure 1: Giant colonic lipoma (45mm) in hepatic flexure – causing complete luminal obstruction resulting in bowel obstruction, necessitating an emergency operation.

82-year male (atypical symptoms) two months history of change in bowel habit, abdominal pain and rectal bleeding. CT colonoscopy showed large colonic lipoma, 4cm in the ascending colon (Figure 1) Colonoscopy showed ulcerated large pedunculated polyp (with fibrotic stock) in the ascending colon. Histology did not demonstrate any malignancy. The GCL was excised completely using the endoscopic submucosal resection technique.

Case 3

57-year-old female presented with a change in her bowel habit habit, rectal bleeding, with a degree of weight loss over the last 6 weeks. On colonoscopy, GCL (10cm) was found to have ulcerated and obstructed the lumen of the colon, which was 40cms from the anal verge. The CT appearances suggested an intussuscepting lesion which has become necrotic (Figure 2). Following a MDT decision, she had a left hemicolectomy and made an uneventful recovery. The histopathology of the specimen confirmed a lipomatous colonic lesion.

Figure 2: Intussusception of a giant colonic lipoma at the sigmoid colon (the arrow indicating the lead point of the intussusception).

Case 4

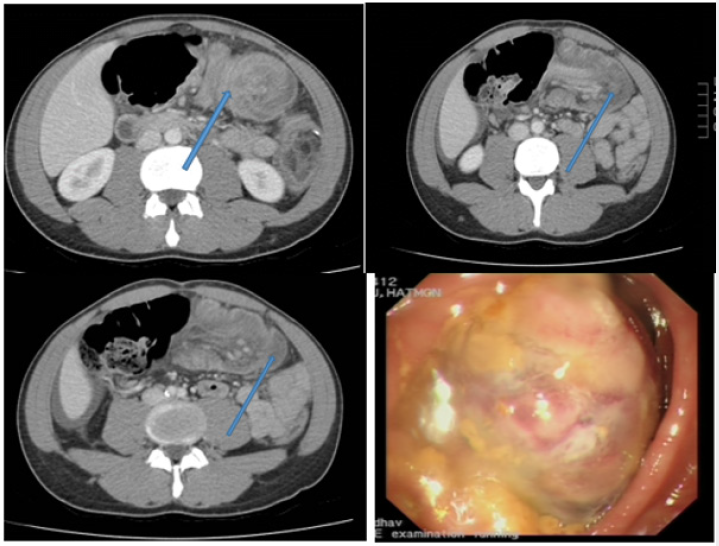

A 37 year old male was admitted as an emergency with a four week history of abdominal pain and a change in bowel habit with passage of mucous. Colonoscopy showed a 35mm pedunculated polyp at the hepatic flexure. CT scan showed substantial intussusception which appears to involve the distal transverse colon, splenic flexure and the proximal descending colon (Figure 1). He underwent an emergency right hemicolectomy for the obstructing intussusception resulting from GCL. He was re-admitted 3 weeks after discharge with features of bowel obstruction, which resolved following conservation management. Histopathology of the resected specimen confirmed lipomatous colonic lesion

Results

A total of 3775 CT colonoscopies were performed over 4 years, 203 (5.3%) cases of CL were reported. 134 (66%) of CL cases were female with a mean age of 77 years. The overall mean size was 1.7cm, with a range of 5mm- 75mm. Of which 0.02% (4/203) were identified as GCL. CL was commonly seen with increasing frequency at hepatic flexure (1%), Transverse (2.6%), sigmoid and transverse colon (3.4%) caecum (5%), ascending (13%), ileocaecal valve(75%), with more than 80% located in the right colon. CL was confidently diagnosed on CT colonography and no further routine imaging or endoscopic assessment was not required. In this series, 23% of CL was greater than 2cm and 4 patients (0.02%) with GCL required surgical or endoscopic intervention.

Discussion

Generally, a lipoma of less than 2 cm is usually asymptomatic, 75% of lipomas greater than 4cm (Giant Lipomas) are associated with symptoms; in particular Paškauskas et al. [7] deduced that intussusception was associated with lipomas less than 4cm. Lipomas are frequently discovered incidently during colonoscopy or radiological imaging. A radiological diagnosis can be made confidently in less than 20% of patients. Barium enema may reveal a radiolucent mass which can demonstrate the pathognomic “squeeze sign”, which change in the size and shape during peristalsis [8]. Contrast tomography (CT) scan expose the smooth demarcated fatty composition of lipomas at absorption densities of -80 to -120 Hounsfield units [9-11]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also useful in detection of lipomas via recognition of the signal intensity of adipose tissue [12,13]. A Koktener et al study advocated the the use of virtual colonoscopy as a tool to diagnose large colonic lipomas [13].

Colonoscopic features consistent to the diagnosis of lipomas include; the “cushion sign” in which a sponge-like impression (Figure 3) is made as biopsy forceps are pressed in the lesion and it then resumes its original shape upon withdrawal [15]. A “naked fat sign” appears as a biopsy is retrieved from the mucosa to reveal protruding fat [16]. “Tenting sign” is demonstrated when the mucosa is grasped with a forceps, if forms a tent shape as it detaches from the underlying lipomatous mass [2]. If there is a clinical concern for malignancy or symptoms arising as a result of colonic lipomas, then endoscopic or surgical excision is indicated [2,17-19]. Various therapeutic interventions have been described on the removal of colonic lipomas. The consensus is that while large colonic lipomas have been resected endoscopically; there is an increased risk of colon perforation when lipomas are broad-based, intramural, or greater than 2 cm in size [17-22]. However, there are reported cases of successful resection of large pedunculated and sessile lipomas without perforation. Kim et al carried out the successful endoscopic removal of 3.8cm lipoma aided by the application of saline solution (with or without epinephrine) into the submucosa deep to the lesion [22]. Jiang et al. recommended surgical removal; for lipomas >4cm (with a sessile appearance or limited pedicle), preoperative diagnostic uncertainty, lesions with substantial symptoms such as intussusception, lesions involving the muscular layer or serosa and lesions that cannot be resected radically under colonoscopy [23].

Figure 3: CT appearance of a colonic lipoma (arrow) and endoscopic appearance of the colonic lipoma- can easily be identified by the stenting sign or the cushion sign and the naked fat sign.

Surgical excision tends to comprise of a limited resection or colotomy with lipomectomy. The type of surgery and resection can depend on diagnostic suspicion and significant symptoms and if the conditions are favorable then laparoscopic surgery is the procedure of choice. Böler DE et al. [24]. advocated Laparoscopic resection as the first choice in treatment of colonic lipomas with various presentations [25]. Endoloop ligation of colonic lipomas appears to be a promising new technique in the management of patients with large colonic lipomas who are otherwise referred for surgery to avoid the high risk of perforation associated with snare cautery. Sessile or broad semipedunculated lesions preclude endoloop placement. In our case series; two patients required emergency hemi-colectomies following presentation of obstructive symptoms and intussusception. Of our two other cases which presented with altered bowel habit; one required an elective laparoscopic colotomy and the other was resected endoscopically. In our series, CT colonograpy provided an effective diagnostic imaging technique for giant colonic lippoma and further sophisticated imaging or endoscopic assessment technique was not required to aid diagnosis.

Conclusion

CL can be confidently diagnosed on CT colonography and no further specialised imaging or endoscopic assessment is required. Whilst, most CL are small and asymptomatic, GCL may mimic polyps and warrant treatment. However, the treatment should be individualised and based on the local expertise. Endoscopic resection of CL >2cm has been advocated by several authors, but this remains controversial.

References

- Pfeil SA, Weaver MG, Abdul Karim FW, Yang P (1990) Colonic lipomas: Outcome of endoscopic removal. Gastrointest Endosc 36: 435-438.

- Liessi G, Pavanello M, Cesari S, Dell’Antonio C, Avventi P (1996) Large lipomas of the colon: CT and MR findings in three symptomatic cases. Abdom Imaging 21: 150-152.

- Jiang L, Jiang LS, Li FY (2007) Giant submucosal lipoma located in the descending colon: A case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 13: 5664-5667.

- Mason R, Bristol JB, Petersen V, Lyburn ID (2010) Education and imaging. Gastrointestinal: lipoma induced intussusception of the transverse colon. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 25: 1177.

- Vecchio R, Ferrara M, Mosca F, Ignoto A, Latteri F (1996) Lipomas of the large bowel. Eur J Surg 162: 915-919.

- Halligan S, Altman DG, Taylor SA (2005) CT colonography in the detection of colorectal polyps and cancer: systematic review, meta-analysis, and proposed minimum data set for study level reporting. Radiology 237: 893-890.

- S Paškauskas, T Latkauskas, G Valeikaite, A Parseliunas, S Svagzdys, et al. (2010) Colonic intussusception caused by colonic lipoma: A case report. Medicina (Kaunas) 46: 477-481.

- Megibow AM, Bosniak MA, Horowitz L (1979) Diagnosis of gastrointestinal lipomas. CT Am J Roentgenol 133: 743-745.

- Heiken JP, Forde KA, Gold RP (1982) Computerized tomography as a definite method for diagnosing gastrointestinal lipomas. Radiology 142: 409-414.

- S Atmatzidis, G Chatzimavroudis, A Patsas, B Papaziogas, S Kapoulas, et al. (2012) Pedunculated cecal lipoma causing colo-colonic intussusception: A rare case report. Case Rep Surg, pp. 279213

- Mnif L, Amouri A, Masmoudi MA, Mezghanni A, Gouiaa N, et al. (2009) Giant lipoma of the transverse colon: a case report and review of the literature. Tunis Med 87: 398-402.

- Arora R, Kumar A, Bansal V (2011) Giant rectal lipoma. Abdom Imaging 36: 545-547.

- Koktener A, Erden A (2007) Usefulness of virtual colonoscopy in the diagnosis of symptomatic large colonic lipomas. Australas Radiol pp. B144-6

- De Be, Er RA, Shinya H (1975) Colonic lipomas, an endoscopic analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 22(2): 90-91.

- Messer J, Waye JD (1982) The diagnosis of colonic lipoma-the naked fat sign. Gastrointest Endosc 28(3): 186-188.

- Franc Law JM, Begin LR, Vasilevsky CA, Gordan PH (2001) The dramatic presentation of colonic lipomata: report of two cases and review of the literature. Am Surg 67(5): 491-494.

- Rogers SO, Lee MC, Ashley SW (2002) Giant colonic lipoma as lead point for intermittent colo colonic intussusception Surgery 131(6): 687-688.

- Mayo CW, Pagtalunan RJG, Brown DJ (1963) Lipoma of the alimentary tract. Surgery 53(5): 598-603

- Pfeil SA, Weaver MG, Abdul Karim FW, Yang P (1990) Colonic lipomas outcome of endoscopic removal. Gastrointest Endosc 36(5): 435-438.

- Raju GS, Gomez G (2005) Endoloop ligation of a large colonic lipoma a novel technique. Gastrointest Endosc 62(6): 988-990.

- Yarze JC (2006) Colonoscopic resection of an asymptomatic colon lipoma. Gastrointest Endosc 63: 890-891.

- Kim CY, Bandres D, Tio TL, Benjamin SB, Al Kawas FH (2002) Endoscopic removal of large colonic lipomas. Gastrointest Endosc 55(7): 929-931.

- Jiang L, Jiang LS, Li FY, Ye H, Li N, et al. (2007) Giant submucosal lipoma located in the descending colon: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol 13(42): 5664-5667.

- Böler DE, Baca B, Uras C (2013) Laparoscopic resection of colonic lipomas When and why. Am J Case Rep 14: 270-275.

- Kaltenbach T, Milkes D, Friedland S, Soetikno R (2008) Safe endoscopic treatment of large colonic lipomas using endoscopic looping technique. Dig Liver Dis 40(12): 958-961.

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...