Lupine Publishers Group

Lupine Publishers

Menu

ISSN: 2637-6636

Research Article(ISSN: 2637-6636)

Access to Oral Health Services in School Children in Camaçari- Bahia- Brazil Volume 7 - Issue 3

Teles, Marcia Pinheiro1, Carvalho, Amanda de Araújo2 and Cangussu Maria Cristina Teixeira3

1Doctorate Student in Dentistry, Federal University of Bahia, Brazil

2Master’s degree in Dentistry, Federal University of Bahia, Brazil

3PhD in Public Health, Titular Professor, Federal University of Bahia, Brazil

Received: February 01, 2022; Published: February 15, 2022

*Corresponding author: Cangussu Maria Cristina Teixeira, PhD in Public Health, Titular Professor, Federal University of Bahia, Brazil

DOI: 10.32474/IPDOAJ.2022.07.000262

Abstract

Objective: To describe access to oral health services in public schools in the age group from 2 to 19 years old, in the city of Camaçari,

Bahia.

Methodology: This is a cross-sectional study involving the participation of 1321 parents of schoolchildren aged between 2 and

19 years old enrolled in public schools in Camaçari, a municipality in the interior of the state of Bahia with approximately 300,000

inhabitants. The collection of data identified in the years 2017 to 2019 and consists of a previous survey with oral parents in the

population’s access to health services, as well as oral health habits. Participation was conditioned to the signing of an informed

consent form by the parents/guardians.

Results: 19% of the study population were female. Most students (67.24%) are up to 10 years old, 32.76% were between 11 and

19 years old. Most 51.31% reported never having gone to the dentist. Almost all did not have dental plans (93.99%). There was

significance in the chi-square test with the variables: sex (p-value= 0.00); having a dental plan (p-value= 0.00); and use of dental

floss (p-value = 0.002).

Conclusion: The lack of access to the health service demonstrates a need to prioritize the age group in health actions in the PNSB

and PSE. A socio-demographic and socio-environmental heterogeneity of the target audience should be considered when being in

education for the same health, intervention measures and becoming effective and comprehensive mainly by enabling access to oral

health.

Keywords: Access of services; epidemiology, school children

Introduction

The need for health is self-perceived and leads individuals

to seek health services. However, in addition to this factor, it also

has the potential for social synthesis and political and ideological

management [1]. It should, however, be understood that the term

“access” refers to the use of health services so that the demands

of each person are met. be remedied. It is noteworthy that the

Brazilian Constitution, in turn, guarantees the right to access to

health care as a relevant way to change the reality of the population

[2]. Access, coverage and use of health services reflect not only the

social structure, but also health inequities. Knowledge of these

data provides, therefore, the articulation of measures aimed at

structuring and implementing an effective health service, regardless

of socioeconomic level or social class [3]. Although Brazil has the

Unified Health System (SUS), a unified and decentralized system

that offers health services to the population, this model faces great

challenges to fulfill its premises, since protective and risk factors

affect the population differently. From this, a great heterogeneity

is determined between social strata, mainly regarding health

inequalities [4]. This is directly reflected in dental care, as people

with reduced income have limited access to oral health services [5].

The SUS prioritizes health protection and promotion actions,

disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation, and

health maintenance, giving primary care its gateway. From this,

care networks are implemented in the most decentralized and

hierarchical way in order to reach the largest number of people

universally, without any barrier [6]. The Family Health Strategy (ESF), National Primary Care Policy (PNAB) and the National Oral

Health Policy (PNSB) were created in order to bring the SUS closer

to its guiding principles in care not centered on the patient/ disease,

but towards promoting health and acting in prevention. With

regard to oral health, the PNSB was created to include oral health

actions in the strategy planned by the health team, since oral health

is included in the broad concept of health. From there, policies are

implemented to ensure that health is offered and provided to all

citizens. As an example, there is an incentive to fluoridate water,

use fluoride toothpaste, access and availability of basic dental care,

whose implementation was guided by the principle of universality

of the SUS [4]. In addition, other measures that cover all aspects

of health are encouraged. such as: encouraging healthy eating

with reduced consumption of sugars, encouraging care with body

and oral hygiene and quitting smoking [7,8]. It should be noted,

however, that despite its implementation nature, water fluoridation

is still unequal in the Brazilian territory, with greater progress in

the South and Southeast regions. It is also observed that the public

water supply system, despite being efficiently expanded, shows

greater restrictions for the North and Northeast regions [4]. Thus,

the effects on the individual’s health occur in a directly proportional

way to this factor.

In oral health, the way in which services are accessed and used

are crucial for coping with dental problems, both in preventive and

rehabilitative actions. Vieira, in 2018, observed that individuals

with low education and family income are more likely to have

never had a dental appointment. For residents of cities with a high

human development index (HDI), there is a 70% lower chance of

never having gone to a dental appointment [3]. In addition, more

egalitarian cities showed better use of oral health care services

in according to the needs of each individual [9]. Reda et al. in

2018, based on a meta-analysis and systematic review, show that

the population residing in urban areas with a higher HDI is more

likely to use the oral health care service. It emphasizes, therefore,

the importance of the context in which the individual lives for the

search for care and care [10]. According to the National Health

Survey (PNS) carried out in 2019, 51.2% of the population aged

0-17 consulted the dentist in 2019. In addition, it was observed that

the higher the level of education and household income, the greater

the proportion of people who consulted the dentist [3,8,11,12].

Regarding the search for health care, only 6.3% sought care due to

a dental problem, toothache or routine dental appointment. The

SB BRASIL, an epidemiological survey carried out periodically to

describe the progression of oral health in the Brazilian population,

identified in 2010 that 18% of children aged 12 years and 13% of

adolescents aged 15-19 years had never been to the dentist [13].

However, it shows a decreasing trend in the severity of dental

caries in adolescents when compared to the survey carried out in

2003, in addition to showing a greater share of the population free

from caries.13 Narvai, in 2006, attributes the downward trend to

the extent of fluoridation of water for public supply, use of fluoride

toothpaste and modification of the focus in public health dentistry

programs in Brazil [14]. However, Roncalli et al in 2015 highlight the

limit of collective actions in the control of the disease and the need

for interventions that cooperate for the reduction of socioeconomic

inequalities so that advances can continue [15]. From the

perspective of collective practices, a relevant example is the Health

Program in Schools, which seeks to make health maintenance

viable with preventive, promotion, attention and health education

actions. (Law No. 6,286, of December 5, 2007, institutes the

School Health Program - PSE, and gives other measures.) [16]. In

this way, students develop means and knowledge to avoid oral

health problems, in addition to being inserted in an environment

that provides motivation and establishment of beneficial habits

with the potential to be perpetuated during adulthood [2]. In this

context, the interdisciplinary team in primary health care plays an

essential role in promoting oral health for schoolchildren, mainly

because they are responsible for identifying health demands and

risk factors early [12].

In addition, the number of dentists associated with the

public service in 2008 and the regions with the most intense

hiring (North and Northeast) demonstrate greater efforts to

overcome established inequalities in coverage. In other words,

a redistribution based on the principle of equity was established

[14]. The American Association of Pediatric Dentistry (AAOP)

emphasizes the importance of oral care initiated in childhood for

its continuation during adolescence and adulthood. The frequency

is defined according to individual needs and risk factors to

which the individual is exposed [17]. In turn, the prevention and

early detection of oral diseases can improve the oral and general

health of the student, as well as their well-being. being and school

performance [18]. For access to health services, including dental

care, factors such as income, education, age, sex and health needs

are influenced. Thus, impacting on oral health care is obtained or

not. However, in addition to good social indicators, equity in health

services intrinsically depends on their supply with human and

technological resources [12]. The form and frequency with which

the health service is accessed reflects the design of equality or

not of a society. For schoolchildren, it demonstrates the existence

of barriers, the way parents and guardians convey the concept of

health and the way they access dental health services. Thus, the

objective of the present study is to describe the access to oral health

services by public school students aged 2-19 years, in the city of

Camaçari, Bahia, Brazil.

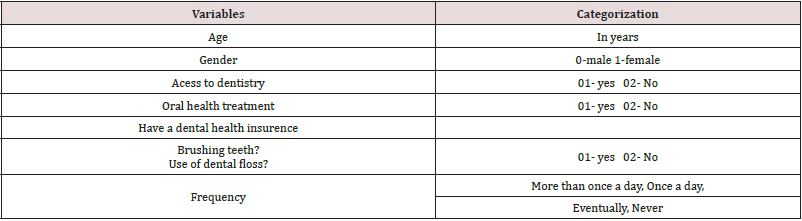

Methodology

This is a cross-sectional study with the participation of 1321 parents of schoolchildren aged 2 to 19 years enrolled in public schools in Camaçari, a municipality in the interior of the state of Bahia, which has approximately 300,000 inhabitants. in an Oral Health Program to be implemented in the school. There was no sample draw, seeking information from the universe of the population to be served. Data collection took place from 2017 to 2019 and consisted of a previous survey with parents to identify this population’s access to oral health services, as well as oral health habits. Participation was conditioned to the signing of the free and informed consent form by the parents/guardians. Questionnaires were sent to parents/guardians with questions present in Table 1, but 12% of them did not return the document. Quantitative and qualitative variables were adopted, self-reported. The variables were dichotomized or grouped into categories, and divided into the following groups: patient identification, anamnesis and oral health status (Table 1). A descriptive analysis of the variables of interest was performed, with observation for simple and relative frequencies and possible associations with the condition of use of the dental service in the last year. using the chi-square test, with a statistical significance of 5%.

Results

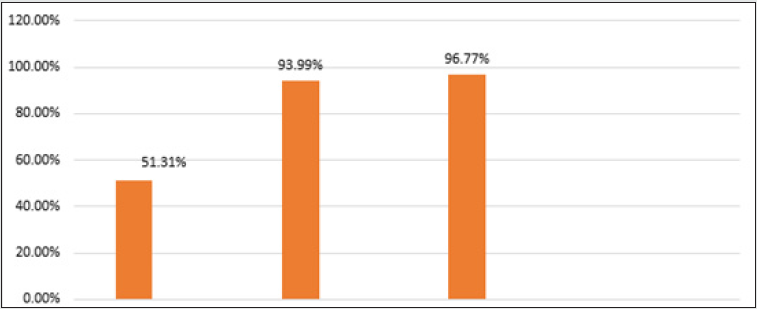

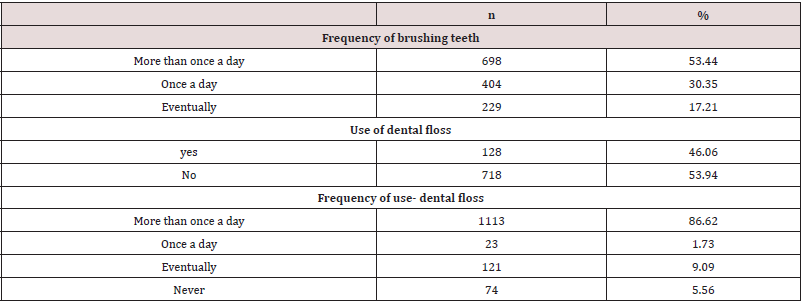

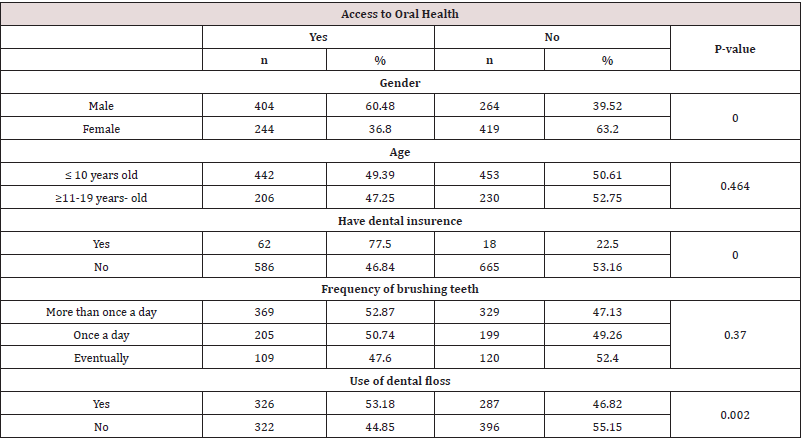

A total of 1321 schoolchildren aged 0-19 enrolled in public schools in Camaçari-Ba participated in the study. 50.19% of the study population was female. Most students (67.24%) are up to 10 years old, 32.76% are between 11-19 years old. Most 51.31% reported never having gone to the dentist. With regard to access to supplementary health, almost all did not have access to dental plans - 93.99%. Regarding ongoing dental treatments, a minority (3.23%) were undergoing treatment (Graphic 1). When evaluating oral hygiene habits, 30.35% of the study population reported brushing their teeth 1x a day, 53.44% brushed more than 1x a day and 17.21% only brushed sometimes. As for the use of dental floss, 53.94% said they did not use it and 46.06% reported using it. Regarding the frequency, 86.62% use it more than 1x a day. Approximately 1.7%, 9.1% and 5.6% use “once a day”, “sometimes” and “rarely”, respectively (Table 2). Table 3 shows the distribution of variables according to attendance at the dentist, where a significant association is identified in the chi-square test with the variables: gender (p-value= 0.00); having a dental plan (p-value= 0.00); ongoing dental treatment (p-value = 0.00) and flossing (p-value = 0.002).

Table 3: Association between access to oral health treatment and other variables in schoolchildren of Camaçari-Ba, Brazil, 2017- 2019.

Discussion

In the present study, only 51% of the population had already

attended dental services and the variables “using dental floss”,

“having a dental plan” and “being male” were significantly associated

with higher frequency of visits to the dentist by schoolchildren

in Camaçari-Ba. . They presented prevalence’s within the study

population of 46.09%, 6.09%, respectively for “using dental floss”,

“having a dental plan”. Regarding the variable “sex”, 50.19% belong

to males and 49.81% to females. The prevalence of access to health

in the study population of 51% highlights possible limits of the

health system that still do not provide access to a considerable

portion of the population. Although there are policies that provide

oral health care, such as PNSB and PSE, data such as those identified

in the present study lead to questioning the limits that lead to these

results. Assis (2012), Antunes (2010) and collaborators mention

that the expansion of oral health care through the SUS faces

concrete barriers such as the low availability of resources, limited

service provision and sociodemographic and socioenvironmental

heterogeneity in the population [19,4]. Thus, it is observed that

availability is not a guarantee for access. The organization of

services, such as the opening hours and shifts offered, can lead to their non-use [20]. It should also be noted that, although the PSE

exists, there is a need for awareness and continuous education in

oral health so that all groups age groups can be covered [21]. It was

also observed that Brazilian adults with low income and schooling

demonstrate great demands and oral problems that mainly result

in the loss of teeth [22].

From this, it is possible to identify a need to prioritize the

school age group in the PSE, in order to encourage adherence

and permanent apprehension of health education. In this way,

individuals would be formed who are more aware of their own

health demands, and consequently, with greater access to health.

In this, access should be considered not only as the availability of

the attention service, but also its use. It is noteworthy that in the

literature on adults, in general, women are more adept to oral

hygiene and prevention habits than men [23]. However, access to

health services was higher among boys in this study. In a study

with children aged 6-12 years, it was identified that male children

who attended public schools are more likely to seek oral health

care services than female children [24]. In a systematic review and

meta-analysis, Reda et al. collaborators state that men, individuals

of different ethnicities or immigrants, people with a lower

educational level or socioeconomic status showed a lower rate of

access to dental health services.10 Vieira and collaborators, in 2018,

bring a lower probability of non-use of services by women , brownskinned

adults and in individuals with perceived dental demands

[3]. When assessing age, Kramer et al. identified that children up to

5 years of age are more likely to use oral health care services [25].

In a cross-sectional study with secondary data on the 2nd and 3rd

cycles of evaluation of the National Program for the Improvement

of Access and Quality of Primary Care, it was observed that women

aged 24-39 showed a lower chance of accessing oral health services

[20]. An important aspect is that the perception of the need for

treatment is a determining factor for the individual to seek health

care.23 However, for children and adolescents, it is observed that

the mother’s perception and educational level can interfere and

modulate the interest in prevention, factors not discussed in this

study [26].

In relation to greater access in those with availability to

supplementary health, it seems to be a condition explained by the

literature and identified in previous studies [27,28]. Individuals with

better socioeconomic conditions are holders of greater possibilities

of adhering to a dental plan, as well as the still insufficiency

of oral health care in the Brazilian public system, makes this a

relevant variable [29]. Dental flossing was also associated with

greater access to oral health services. The acquisition of dental

floss, a means that enables the construction and maintenance of

the habit, can be closely associated with socioeconomic status/

family income. This can also be related to socioeconomic status,

since the most socioeconomically disadvantaged groups have a

higher prevalence of caries [30]. As they more frequently access

means of prevention, this group shows less frequent oral demands,

but also greater appreciation of maintaining a health condition.

satisfactory mouthpiece [24]. In addition, better oral habits are

related to educational level. The health education offered interferes

with the perpetuation and adoption of hygiene and eating habits

that will enable the maintenance of oral health and the perception

of the need for access to services of this kind [10]. In addition,

Chiavegatto et al. poor does not necessarily constitute a barrier

to accessing health services. Factors such as the availability of an

adequate network of health services, educational level and social

appreciation of oral health have a great influence on adherence

to and access to health services [31]. The results concerning this

work, despite the significant sample size, have the limit of selfresponse

by parents and guardians, as well as the impossibility of

exploring other social, conjunctural and organizational variables

of the health services involved in this process. Thus, comparative

studies with population surveys on the prevalence of access to oral

health services and associated factors in the school age group are

necessary in order to corroborate the results of the present study.

The inequity in the distribution and availability not only of public

health services but also of means of prevention and promotion of

oral health is highlighted. Thus, it is of fundamental importance

that they are available not only in cities with a larger population,

but also in small and medium-sized ones, in order to control oral

disease in this group.

Conclusion

Most schoolchildren aged 0-19 in Camaçari-Ba have never been to the dentist (51.31%), do not have ongoing dental treatment (96.77%) and do not have a dental plan (94%). The variables “flossing”, “having a dental plan” and “being male” were significantly associated with access to the dentist.

References

- Cruz DN, Chaves S, Cangussu MC (2016) A utilização dos serviços odontológicos: elementos teóricos e conceituais. in Chaves, S. C. Política de Saúde Bucal no Brasil. Editora EDUFBA.

- Valarelli FP, Franco RM, Sampaio CC, Mauad C, Passos VAB, et al. (2011) Importância dos programas de educação e motivação para saúde bucal em escolas: relato de experiê Odontol Clín Cient 10(2): 173-176.

- Vieira JMR, Rebelo MAB, Martins NMO, Gomes JFF, Vettore MV (2018) Contextual and individual determinants of non-utilization of dental services among Brazilian adults. Journal of Public Health Dentistry 79(1): 60-70.

- Antunes JLF, Narvai PC (2010) Políticas de saúde bucal no Brasil e seu impacto sobre as desigualdades em saú Rev Saúde Pública 44(2): 360-365.

- Pucca GA Jr, Gabriel M, de Araujo ME, de Almeida FC (2015) Ten years of a National Oral Health Policy in Brazil: innovation, boldness, and numerous challenges. J Dent Res 94: 1333–1337.

- Paim SJ (2016) O que é o SUS. Editora Fiocruz

- (2012) BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde: Política Nacional de Atenção Bá 1a edição. Brasília.

- (2004) BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde: Diretrizes da Política Nacional de Saúde Bucal. Brasí

- Bhandari B, Newton JT, Bernabé E (2015) Income inequality, disinvestment in health care and use of dental services. J Public Health Dent 75: 58–63.

- Reda SF, Reda SM, Thomson WM, Schwendicke F (2018) Inequality in utilization of dental services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 108: e1–7.

- (2019) BRASIL Ministério da Saúde. Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde: Informações sobre domicílios, acesso e utilização dos serviços de saúde em.

- Zambaldi MPM, Molina MCB, Prado CB, Santos Neto ET (2021) Acesso a bens e serviços de saúde bucal por escolares de 7 a 10 anos em Vitória-ES. Revista de Odontologia da Unesp 50: e20210030.

- (2012) BRASIL Ministério da Saú Projeto SB Brasil 2010: Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde Bucal: Resultados principais. Brasília, DF.

- Narvai PC, Frazão P, Roncalli AG, Antunes JLF (2006) Cárie dentária no Brasil: declínio, polarização, iniqüidade e exclusão social. Rev Panam Salud Publica19(6): 385–393.

- Roncalli AG, Sheiham A, Tsakos G, Watt RG (2015) Socially unequal improvements in dental caries levels in Brazilian adolescents between 2003 and 2010. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 43(4): 317–324.

- (2007) Institui o Programa Saúde na Escola – PSE, e dá outras providências. Diário Oficial da União 07 dezembro; seção 1. P.2.

- American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry (2018) Policy on the role of dental prophylaxis in pediatric dentistry. Pediatr Dent 40(6): 47-48.

- (2020) Periodicity of examination, preventive dental services, anticipatory guidance/ counseling, and oral treatment for infants, children, and adolescents. The Reference Manual of Pediatric Dentistry. Chicago, Ill, USA American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry pp. 232-242.

- Assis MMA, Jesus WLA (2012) Acesso aos serviços de saúde: abordagens, conceitos, políticas e modelos de aná Cienc Saude Colet 17(11): 2865-2875.

- Freire DEWG, Freire AR, Lucena EHG, Cavalcanti YW (2021) Acesso em saúde bucal no Brasil: análise das iniquidades e não acesso na perspectiva do usuário, segundo o Programa de Melhoria do Acesso e da Qualidade da Atenção Básica, 2014 e 2018. Epidemiol. Serv Saude Brasília 30(3): e2020444.

- Carreiro, Danilo Lima (2019) Acesso aos serviços odontológicos e fatores associados: estudo populacional domiciliar. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 24(3): 1021-1032.

- Fonseca LLV, Nehmy RMQ, Mota JAC (2015) O valor social dos dentes e o acesso aos serviços odontoló Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 20(10): 3129-3138.

- Davoglio RS, Aerts DRGC, Abegg C, Freddo SL, Monteiro L (2009) Fatores associados a hábitos de saúde bucal e utilização de serviços odontológicos entre adolescentes. Cad Saúde Pública 25(3): 655-667.

- Villalobos-Rodelo JJ, Medina-Solis CE, Maupomé G, Lamadrid-Figueroa H, Casanova-Rosado AJ, et al. (2010) Dental Needs and Socioeconomic Status Associated with Utilization of Dental Services in the Presence of Dental Pain: A Case-Control Study in Children. J Orofac Pain 24(3): 279-286.

- Kramer PF, Ardenghi TM, Ferreira S, Fischer LA, Cardoso L, (2008) Use of dental services by preschool children in Canela, Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica 24(1): 150-156.

- Machry (2013) Socioeconomic and psychosocial predictors of dental healthcare use among Brazilian preschool children. BMC Oral Health 13: 60.

- Teusner D, Brennan D, Spencer A (2015) Associations between level of private dental insurance cover and favourable dental visiting by household income. Aust Dent J 60: 479-89.

- Pilotto LM, Celeste RK (2018) Tendências no uso de serviços de saúde médicos e odontológicos e a relação com nível educacional e posse de plano privado de saúde no Brasil, 1998-2013. Cad Saúde Pública 34(4): e00052017.

- Fonseca EP, Frias Ac, Mialhe FL, Pereira AC, Meneghim MC (2017) Factors associated with last dental visit or not to visit the dentist by Brazilian adolescents: A population-based study. PLoS ONE 12(8): e0183310.

- Sousa FS, Lopes BC, Costa EM, Alves CMC, Queiroz RCS, et al. (2021) Persistem iniquidades sociais na distribuição da cárie dentária em adolescentes maranhenses? Contribuições de um estudo de base populacional. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 26(7): 2625-2634.

- Chiavegatto Filho ADP, Wang YP, Malik AM, Takaoka J, Viana MC, et al. (2015) Determinants of the use of healthcare services: multilevel analysis in the Metropolitan Region of Sao Paulo. Rev Saude Publica 49: 15.

Editorial Manager:

Email:

pediatricdentistry@lupinepublishers.com

Top Editors

-

Mark E Smith

Bio chemistry

University of Texas Medical Branch, USA -

Lawrence A Presley

Department of Criminal Justice

Liberty University, USA -

Thomas W Miller

Department of Psychiatry

University of Kentucky, USA -

Gjumrakch Aliev

Department of Medicine

Gally International Biomedical Research & Consulting LLC, USA -

Christopher Bryant

Department of Urbanisation and Agricultural

Montreal university, USA -

Robert William Frare

Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology

New York University, USA -

Rudolph Modesto Navari

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

University of Alabama, UK -

Andrew Hague

Department of Medicine

Universities of Bradford, UK -

George Gregory Buttigieg

Maltese College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Europe -

Chen-Hsiung Yeh

Oncology

Circulogene Theranostics, England -

.png)

Emilio Bucio-Carrillo

Radiation Chemistry

National University of Mexico, USA -

.jpg)

Casey J Grenier

Analytical Chemistry

Wentworth Institute of Technology, USA -

Hany Atalah

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Mercer University school of Medicine, USA -

Abu-Hussein Muhamad

Pediatric Dentistry

University of Athens , Greece

The annual scholar awards from Lupine Publishers honor a selected number Read More...